The 2022 Nobel Prize in physics recognized three scientists who made groundbreaking contributions in understanding one of the most mysterious of all natural phenomena: quantum entanglement.

In the simplest terms, quantum entanglement means that aspects of one particle of an entangled pair depend on aspects of the other particle, no matter how far apart they are or what lies between them. These particles could be, for example, electrons or photons, and an aspect could be the state it is in, such as whether it is “spinning” in one direction or another.

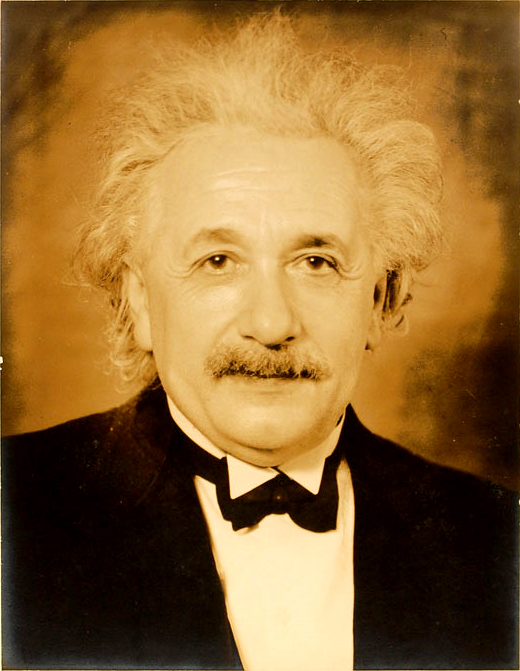

The strange part of quantum entanglement is that when you measure something about one particle in an entangled pair, you immediately know something about the other particle, even if they are millions of light years apart. This odd connection between the two particles is instantaneous, seemingly breaking a fundamental law of the universe. Albert Einstein famously called the phenomenon “spooky action at a distance.”

Having spent the better part of two decades conducting experiments rooted in quantum mechanics, I have come to accept its strangeness. Thanks to ever more precise and reliable instruments and the work of this year’s Nobel winners, Alain Aspect, John Clauser and Anton Zeilinger, physicists now integrate quantum phenomena into their knowledge of the world with an exceptional degree of certainty.

However, even until the 1970s, researchers were still divided over whether quantum entanglement was a real phenomenon. And for good reasons – who would dare contradict the great Einstein, who himself doubted it? It took the development of new experimental technology and bold researchers to finally put this mystery to rest.

Existing in multiple states at once

To truly understand the spookiness of quantum entanglement, it is important to first understand quantum superposition. Quantum superposition is the idea that particles exist in multiple states at once. When a measurement is performed, it is as if the particle selects one of the states in the superposition.

For example, many particles have an attribute called spin that is measured either as “up” or “down” for a given orientation of the analyzer. But until you measure the spin of a particle, it simultaneously exists in a superposition of spin up and spin down.

There is a probability attached to each state, and it is possible to predict the average outcome from many measurements. The likelihood of a single measurement being up or down depends on these probabilities, but is itself unpredictable.

Though very weird, the mathematics and a vast number of experiments have shown that quantum mechanics correctly describes physical reality.

Two entangled particles

The spookiness of quantum entanglement emerges from the reality of quantum superposition, and was clear to the founding fathers of quantum mechanics who developed the theory in the 1920s and 1930s.

To create entangled particles you essentially break a system into two, where the sum of the parts is known. For example, you can split a particle with spin of zero into two particles that necessarily will have opposite spins so that their sum is zero.

In 1935, Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen published a paper that describes a thought experiment designed to illustrate a seeming absurdity of quantum entanglement that challenged a foundational law of the universe.

A simplified version of this thought experiment, attributed to David Bohm, considers the decay of a particle called the pi meson. When this particle decays, it produces an electron and a positron that have opposite spin and are moving away from each other. Therefore, if the electron spin is measured to be up, then the measured spin of the positron could only be down, and vice versa. This is true even if the particles are billions of miles apart.

This would be fine if the measurement of the electron spin were always up and the measured spin of the positron were always down. But because of quantum mechanics, the spin of each particle is both part up and part down until it is measured. Only when the measurement occurs does the quantum state of the spin “collapse” into either up or down – instantaneously collapsing the other particle into the opposite spin. This seems to suggest that the particles communicate with each other through some means that moves faster than the speed of light. But according to the laws of physics, nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. Surely the measured state of one particle cannot instantaneously determine the state of another particle at the far end of the universe?

Physicists, including Einstein, proposed a number of alternative interpretations of quantum entanglement in the 1930s. They theorized there was some unknown property – dubbed hidden variables – that determined the state of a particle before measurement. But at the time, physicists did not have the technology nor a definition of a clear measurement that could test whether quantum theory needed to be modified to include hidden variables.

Disproving a theory

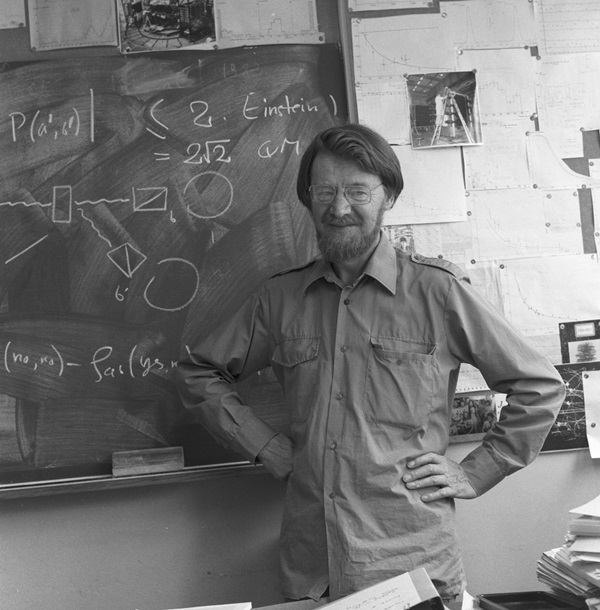

It took until the 1960s before there were any clues to an answer. John Bell, a brilliant Irish physicist who did not live to receive the Nobel Prize, devised a scheme to test whether the notion of hidden variables made sense.

Bell produced an equation now known as Bell’s inequality that is always correct – and only correct – for hidden variable theories, and not always for quantum mechanics. Thus, if Bell’s equation was found not to be satisfied in a real-world experiment, local hidden variable theories can be ruled out as an explanation for quantum entanglement.

The experiments of the 2022 Nobel laureates, particularly those of Alain Aspect, were the first tests of the Bell inequality. The experiments used entangled photons, rather than pairs of an electron and a positron, as in many thought experiments. The results conclusively ruled out the existence of hidden variables, a mysterious attribute that would predetermine the states of entangled particles. Collectively, these and many follow-up experiments have vindicated quantum mechanics. Objects can be correlated over large distances in ways that physics before quantum mechanics can not explain.

Importantly, there is also no conflict with special relativity, which forbids faster-than-light communication. The fact that measurements over vast distances are correlated does not imply that information is transmitted between the particles. Two parties far apart performing measurements on entangled particles cannot use the phenomenon to pass along information faster than the speed of light.

Today, physicists continue to research quantum entanglement and investigate potential practical applications. Although quantum mechanics can predict the probability of a measurement with incredible accuracy, many researchers remain skeptical that it provides a complete description of reality. One thing is certain, though. Much remains to be said about the mysterious world of quantum mechanics.

![]()

Andreas Muller, Associate Professor of Physics, University of South Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.