Key Takeaways:

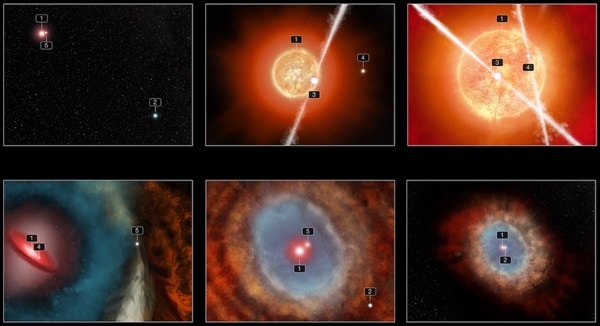

When the first five images from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) were unveiled, one of them stared at me with two eyes. It was an image of the Southern Ring Nebula, NGC 3132, and smack in the middle were two bright stars.

Now, the fact that NGC 3132 houses a binary star system (two stars orbiting one another) has been known since the days of the Hubble Space Telescope.

But in those early images, the central star that ejected the nebula – a tiny, hot white dwarf – was so dim it was almost invisible next to its bright Sun-like companion. In effect, the nebula had one eye almost closed.

But the JWST reveals more than Hubble did. It can collect “cooler” photons (light particles) in the infrared range of the electromagnetic spectrum. In this cooler light, we saw both stars in the binary system shining as bright as one another: two glaring eyes!

This was surprising to any astronomer who understands this type of nebula; super-hot white dwarfs typically don’t shine brightly in infrared light. It made sense for the cooler star to be shining this way, but observing the same brilliance from its partner was unexpected.

Emails started to bolt coast to coast and across oceans as astronomers pieced the puzzle together. The central white dwarf star of NGC3132, they realised, is enshrouded in dust. The dust is warmed up by the star’s heat and therefore shines in the infrared, producing the light we observed.

It was this that led us on the trail to find out what was really happening in the Southern Ring Nebula. Our findings from a team of nearly 70 astronomers are published Dec. 8 in Nature Astronomy.

At the heart, a hot white dwarf

The Southern Ring Nebula is a planetary nebula. That means it’s a gaseous nebula formed by a Sun-like star shedding most of its gas in the last act before its demise.

Once it shed much of its mass, the star became a hot white dwarf. This central star now sits in the middle of the nebula, cooling like a stellar ember, effectively dying.

The beauty of planetary nebulae is they can be looked at forensically: parts of the nebula farther from the middle were ejected earlier in time. In this way, the entire nebula functions a bit like a geological record.

With its dying white dwarf in the centre, our group approached NGC 3132 like a crime scene.

Two unknown suspects emerge

First, we quickly realised the dust making the central star shine so brightly was actually a disk wrapped closely around the central star that must have been forged by a companion. This orbiting companion star would have stripped gas away from the central star, hastening its demise.

We didn’t spot the companion, though. We think it’s either too faint to detect, or has potentially perished in the interaction and merged with the central star.

Then we noticed something else: broken concentric arches engraved in the extended halo of the nebula. These also betrayed the presence of an orbiting companion. Could this culprit be the same one that forged the disk of dust?

We don’t think so. Although the arches have suffered some “weathering”, our measurements of them betray the presence of yet another companion star. This one is placed a little too far from the central star to have created the dust disk.

And just like that, we had gathered evidence the Southern Ring Nebula contains not just two stars in a binary system, but four.

And we would gather more yet.

Tied up in a bumpy, gassy bubble

The “ring” that gives the nebula its name is actually the wall of an egg-shaped bubble containing hot gas, heated by the central star. This wall is marked with noticeable protuberances.

Combining the JWST image with data from the European Southern Observatory, our team created a 3D model that revealed these protuberances come in pairs, moving in opposite directions away from the central star.

One possible explanation is the interaction that created the dust disk didn’t involve just one close companion, but two. In other words, we’re looking at a potential fifth star in the mix – interacting chaotically with the central star to blow out jets that push out those protuberances.

This fifth star’s presence is still tentative. But we can say with a good degree of certainty the stellar system that created the Southern Ring Nebula comprises not just the binary star system (the two eyes of the nebula), but also a third star that ripped away the gas to form the disk, and another that inscribed a track of concentric arches in the gas bubble.

As for the second eye of the nebula – the one we’d always known about – it was definitely an innocent bystander. It’s too far from the central star to have participated in its demise.

One case closed, more to come

The case of the Southern Ring Nebula isn’t the only one demonstrating how stars work in packs. Much of stellar astrophysics is being revisited today in light of the realisation of just how gregarious stars can be. And we’re all the more excited for it.

A wealth of phenomena arise from stellar interactions, from supernova explosions, to the merging of black holes and neutron stars giving rise to gravitational wave events.

As the JWST delivers more detailed images of the universe, astronomers will be keenly dusting off their gloves to tackle more mysteries.

![]()

Orsola De Marco, Professor of Astrophysics, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.