The number of known exoplanets has veritably exploded in recent years, with more than 5,000 worlds beyond our solar system now known. But there’s a catch: The worlds we’ve found are typically those easiest to detect. It’s only as techniques and technology improve that astronomers are able to discover planets that are harder to see.

Now, the field has made another step forward with two recent papers: one published Dec. 23 and one published April 21, both in The Astrophysical Journal. In them, researchers show how they’ve used machine learning to spot the subtle signs of forming planets within the thick disks of dust that surround young stars. Such a tool could improve how quickly and efficiently astronomers can find young planets — and it comes right at a time when new and upcoming telescopes are poised to provide an avalanche of data on exoplanets in the Milky Way.

What’s in a protoplanetary disk?

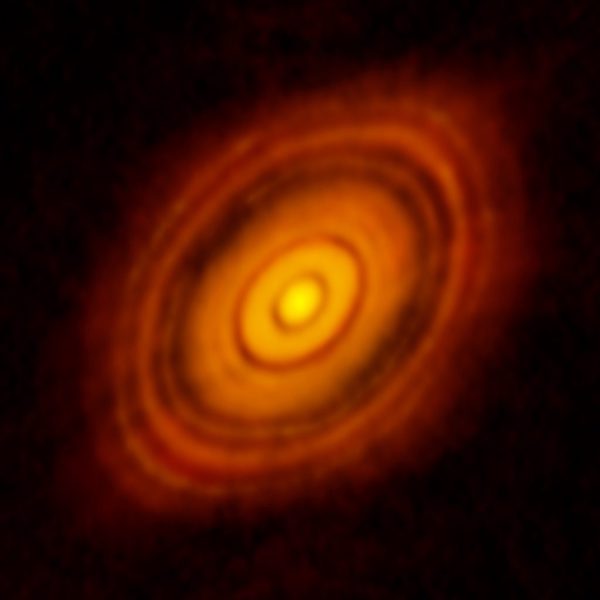

When a star is born, it lies ensconced within a thick disk of dust and gas. It is this disk, called a protoplanetary disk, that provides the material from which planets form over millions of years.

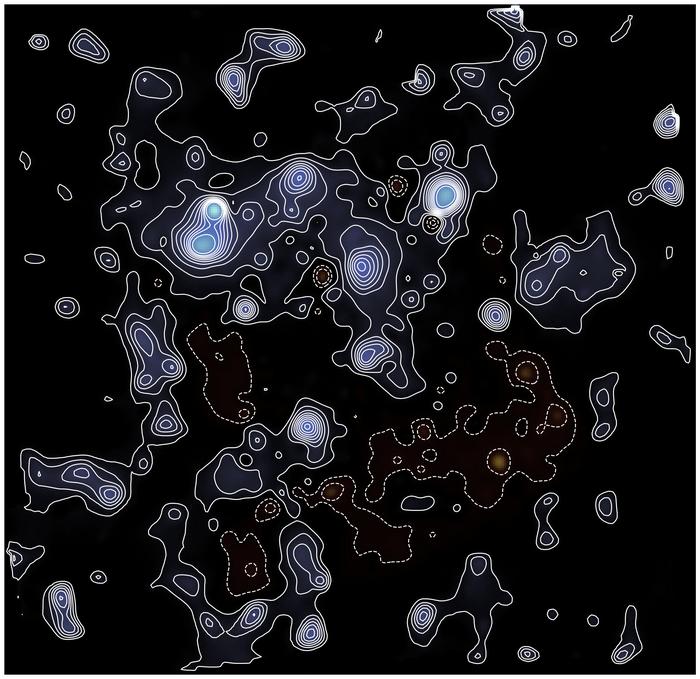

Astronomers find and study these often massive and far-reaching disks using infrared and radio light. But discovering any young planets embedded within such disks is difficult: The dense material obscures our view, forcing astronomers to infer the presence of planets through their effects on the disk itself.

In these cases, astronomers indirectly find the still-forming worlds by looking at how they affect their surroundings, changing the way nearby material orbits and eventually carves out gaps in the disk. It is those gaps that serve as beacons telling astronomers “Look here!”

AI to the rescue

Traditionally, such searches have been carried out manually, explained lead author and doctoral student Jason Terry, of the University of Georgia in Athens, in a press release. Researchers study numerous images looking for any telltale signs of forming planets, then run possible finds through multiple simulations to determine whether they’ve spotted something real or not.

But astronomers, as the saying goes, are only human. Manual searches take time, and humans can miss difficult-to-find clues, such as when the metaphorical waves made by a burgeoning planet are tiny compared to the motions of the rest of the disk.

That’s where AI comes in. With its ability to quickly analyze large amounts of data and pick up on subtle hints that humans might miss, this tool has now proven it is a valuable time- and money-saving resource in the hunt for new worlds — including those we might otherwise overlook.

The team’s studies focused on training a machine learning algorithm to find young planets embedded within disks using completely synthetic data. Once the AI was trained up, however, they turned it loose on real observations to determine whether the algorithm could identify known exoplanets — and possibly find new ones.

“This has never been done before in our field and paves the way for a deluge of discoveries as James Webb Telescope data rolls in,” said University of Georgia assistant professor and study co-author Cassandra Hall.

The result was a resounding success. Not only did the AI accurately point to the places in disks where planets are known to be forming, it also flagged the disk around the star HD 142666, where astronomers previously hadn’t identified any planets.

When the team followed up by running simulations on the potential find, “[we] found that a planet could recreate the observation,” Terry said in a second release on the discovery. The team concluded that HD 142666 hosts a planet five times the mass of Jupiter orbiting about 75 times farther than Earth sits from the Sun.

“We knew from our previous work that we could use machine learning to find known forming exoplanets,” said Hall. “Now, we know for sure that we can use it to make brand-new discoveries.”

More out there

According to the study authors, finding actively forming planets is an area where AI has rarely been applied. But it is also an area that stands to benefit greatly from the tool’s use, particularly because of the delicate and difficult nature of the work.

“In a sense, we’ve sort of just made a better person,” said Terry. “This method is one, really fast, and two, its accuracy gets planets that humans would miss.”

He acknowledged that scientists are often skeptical of adopting AI, but he also emphasized that the algorithm is clearly up to the task. “In this case, we have very concrete results that demonstrate the power of this method,” he said.

Racking up additional planets is about more than just reaching increasingly impressive numbers. The more planets astronomers find, the more they can learn about what’s normal, what’s not, and why certain worlds might form under some conditions but not others.

We already know that our own solar system lacks some of the most commonly found worlds — rocky planets with masses between that of Earth and Neptune — but not why. So, catching young stars in the act of forming planets, whether with a human eye or a machine learning algorithm, is one of the best ways to piece together the complex history of our solar system and the others we’ve found.