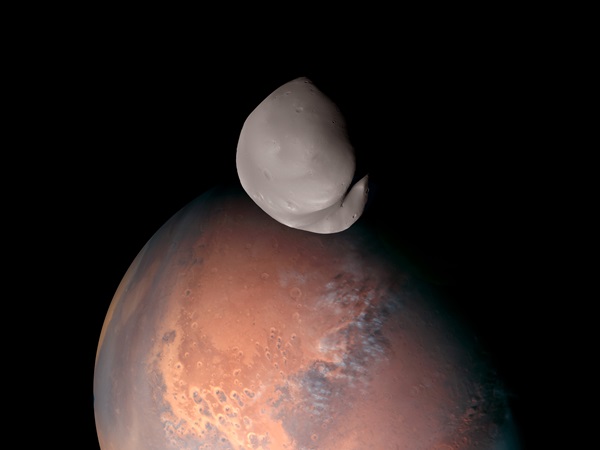

Stunning new views of Deimos, one of Mars’ two strange moons, hint at questions about how the martian moons formed in the first place — and why they are still in orbit around Mars today. These questions have perplexed scientists since the discovery of the martian moons Phobos and Deimos almost 150 years ago.

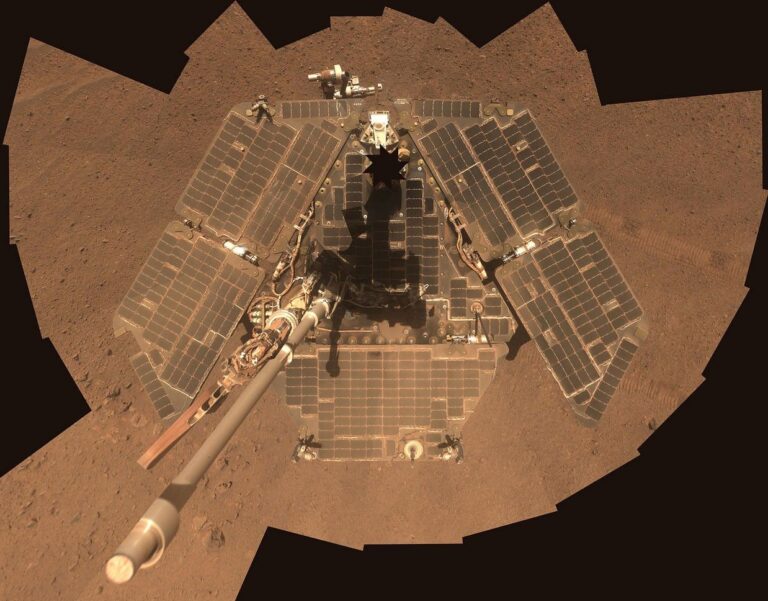

The latest photographs are from the United Arab Emirates’ Hope spacecraft, a robotic probe that has been orbiting the Red Planet since 2021. On March 10, the Hope obiter made its first of several proposed flybys of the smaller moon Deimos, which is only 7.7 miles (12.4 kilometers) wide. Following the flyby, Hope sent back photographs of Deimos’ farside, which has never been seen up-close before.

Hope got as close to Deimos as anyone (or anything) is likely going to get for a while. “This was approximately 100 kilometers [62 miles] up, and I don’t believe we will get that close again,” Hessa Al Matroushi, the science lead for the Emirates Mars Mission, tells Astronomy.

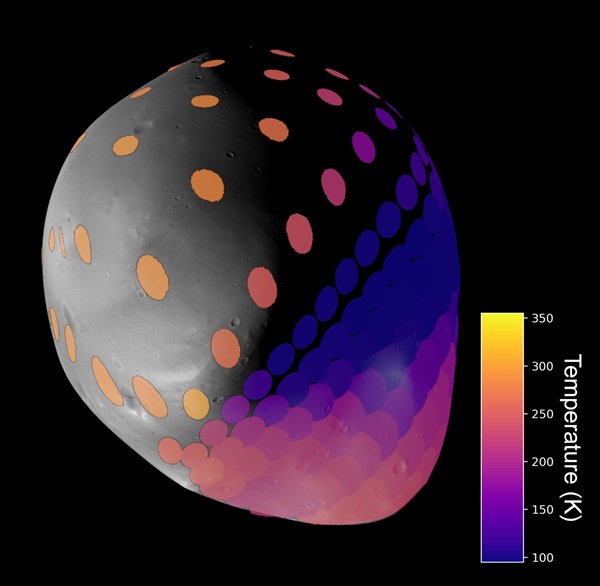

During additional flybys of Deimos planned for later this year, “we’re going to get to around 200 kilometers [124 miles], and that’s still pretty good data,” she says. “That will help us understand the moon.”

Are Phobos and Deimos captured asteroids?

The mission to take the new photos of Deimos, with Mars looming large in the background, allowed the probe’s two spectrometers to record crucial data about the moon’s composition.

These initial readings are preliminary and will be refined in later flybys. But they suggest Deimos is made of rocky material similar to Mars itself, and not the carbon-rich rock that would be expected if Deimos was a captured asteroid, as scientists once suspected.

That supports theories that both Deimos and Phobos — Mars’ larger moon, which is nearly 17 miles (27 km) across at its widest point — formed in orbit when a large object, perhaps a dwarf planet, struck Mars in the distant past. If confirmed, that would put to rest long-standing theories that both Phobos and Deimos are asteroids that have been captured by Mars’ gravity.

But many questions remain, including whether Phobos has the same composition as Deimos. Both Martian moons are also small and irregularly shaped, which supports the idea they are captured asteroids; and both are optically very dark, unlike Mars itself, which suggests they may have a different origin than the Red Planet.

Understanding the origins of Phobos and Deimos

The two moons of Mars, Phobos and Deimos, were discovered in 1877 by the American astronomer Asaph Hall using the 26-inch refractor telescope at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington D.C.

Hall named the martian moons after the charioteers of the war god Ares — the Greek version of Mars. As described in Homer’s Iliad, Deimos personified the dread felt before a battle, and Phobos personified the panic felt during battle. (Some sources suggest Deimos and Phobos were actually the horses of Ares, possibly because he also had a horse named Phobos.)

The moons of Mars have been enigmas since their discovery. Phobos has a low orbit, about 3,700 miles (6,000 km) above the martian surface, and it zips across the martian sky in just four hours. But Deimos orbits much farther out, at a distance of some 14,500 miles (23,500 km), and it circles the Red Planet almost as fast as Mars rotates.

Both moons are tidally locked to Mars, so they always present the same face to the rusty world. Phobos and Deimos occasionally transit between Mars and the Sun, but neither is large enough to completely eclipse it. Both moons are roughly potato-shaped, not spherical like Earth’s Moon, which gives strength to the idea that they’re captured asteroids. But the idea they were originally part of the Red Planet has always been a possibility, says Abigail Fraeman, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The impact theory suggests both Phobos and Deimos formed when an object the size of Ceres smashed into the martian protoplanet; and that Phobos may periodically break apart into a ring of dust, from which it reforms. The moons might also be remnants of a larger martian moon that broke up in the past; or they might have both formed from rings; or maybe they formed alongside Mars from the protoplanetary disk around the Sun. Scientists just don’t know for sure.

“This is one of the big, outstanding mysteries in planetary science,” Fraeman tells Astronomy. “However they formed, there are broad implications for our understanding of the solar system.”

MMX: A new mission to explore Mars’ moons

Fraeman is one of more than a dozen American scientists who will soon study Phobos and Deimos as part of the Martian Moons Exploration Mission (MMX), a robotic probe scheduled to launch in 2024 and arrive at the Red Planet a year later.

MMX is being led by the Japanese space agency JAXA, with participation by space agencies from several other nations. NASA has engaged the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University to build a gamma-ray and neutron spectrometer called MEGANE for the probe. And last month, NASA announced 10 American scientists who will work on the MMX mission.

The plan is for the MMX probe to first visit both Phobos and Deimos. Then it will attempt to land on Phobos, collect samples from the moon’s surface, and return those samples to Earth in 2029. American scientists will be among those given the opportunity to analyze the samples.

Fraeman’s own work will be to investigate the composition of the martian moons using measurements taken by the instruments on the MMX probe. Other scientists will study the moons’ orbital dynamics in search of clues about both their composition and structure. And still more researchers will study the moons’ surfaces — which photographs show are peppered with craters, but still appear smoother than expected — as well as the moons’ thermophysical properties, which might help explain why Phobos and Deimos look like they do.

“There’s no one idea that explains all of the observations that we’ve made,” Fraeman says. “So there’s something that we’re not quite getting, either about how to put the observations together, or another thing that we haven’t yet thought of … the martian moons are so much fun.”