Friday, January 7

The Moon slides just 4° south of the distant planet Neptune at 5 A.M. EST. The two aren’t visible then, but will appear in the evening sky after sunset, separated by 7° an hour after the Sun disappears. Although the Moon is the easiest naked-eye object to view in the night sky, you’ll need binoculars or a telescope to pick out Neptune’s dim, magnitude 7.8 glow. You can find it by first locating Jupiter — magnitude –2.1 — and then scanning 19° east-northeast of the giant planet. You’ll pick up Neptune just over 3° northeast of the 4th-magnitude star Phi (ϕ) Aquarii.

Also visible in the evening sky, Mercury reached its greatest eastern elongation (19°) from the Sun earlier this morning at 6 A.M. EST. At sunset, it shines at magnitude –0.5 in the west, 14° high in Capricornus and a little less than 6° west-southwest of magnitude 0.7 Saturn. Keep an eye on this particular pair of planets — they’ll continue drawing nearer to each other over the next several days, coming closest later this week.

Sunrise: 7:22 A.M.

Sunset: 4:51 P.M.

Moonrise: 10:58 A.M.

Moonset: 10:39 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (30%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Saturday, January 8

Venus reaches inferior conjunction with the Sun at 8 P.M. EST, rendering it invisible. The bright planet will remain hidden for another several days, then pop back out as a morning star in the predawn sky later this month.

Although Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard) has been stealing headlines as of late, now is the perfect time to pick up Comet 19P/Borrelly, currently located roughly halfway between magnitude 2 Diphda and magnitude 3.6 Iota (ι) Ceti in Cetus the Whale.

Currently reported around magnitude 10, Borrelly is fainter than Leonard but still easy to snag in a 4- to 6-inch scope under good skies. Look for its slightly out-of-round gray, cotton ball-like glow some 6° north-northeast of Diphda this evening. This comet, discovered in 1904, returns every 6.8 years. It was the third comet ever visited by a spacecraft, which occurred in 2001 when Deep Space 1 sent back pictures of this 5-mile-long (8 kilometers), bowling pin-shaped space rock.

Sunrise: 7:22 A.M.

Sunset: 4:52 P.M.

Moonrise: 11:22 A.M.

Moonset: 11:44 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing crescent (40%)

Sunday, January 9

First Quarter Moon occurs at 1:11 P.M. EST. Our satellite is visible all afternoon and evening today, setting shortly after midnight on the 10th. That makes it easy to observe the rich detail present on the visible lunar face. Even a casual observer will notice dark areas — ancient “seas” of cooled lava — and whiter regions — rugged highlands. Also notice how these are distributed: The seas, or maria, seem appear in the northern hemisphere, while the lunar south is marked by lighter terrain and deep craters.

Right at the terminator separating night and day, you can also see several notable craters in stark shadow. The most prominent are Hipparchus and Albategnius, just south of the lunar equator.

Sunrise: 7:22 A.M.

Sunset: 4:53 P.M.

Moonrise: 11:45 A.M.

Moonset: —

Moon Phase: First Quarter

Monday, January 10

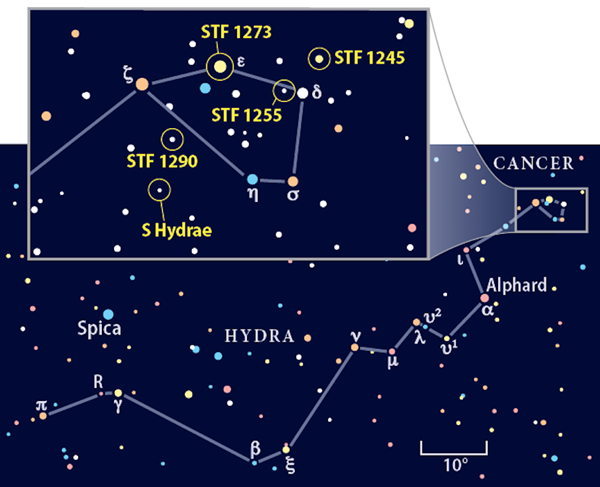

Early-morning observers up before the Sun can enjoy a full view of Hydra the Water Snake this morning. Covering roughly 1,303 square degrees, this is the largest of the officially recognized 88 constellations in our sky. That may seem intimidating to observe, so let’s zoom in on only its head, which covers a smaller, more manageable 20°.

The Water Snake’s head lies adjacent to Cancer the Crab and some 15.5° east of bright Procyon in Canis Minor. The head itself is depicted by the stars Zeta (ζ), Epsilon (ϵ), Delta (δ), Sigma (σ), and Eta (η) Hydrae. First, focus in on Epsilon with your telescope — this is not a single luminary but in fact a double star, also cataloged as Struve (STF) 1273. Its components are magnitude 3.5 and 6.7, and sit a mere 2.9″ apart. You’ll need steady seeing and about a 5-inch scope to split them. Can you do it?

If you want an easier double to observe, slide over to Delta and then look 1° north to spot STF 1245. These are both fainter at magnitude 6.0 and 7.2, but separated by a wider 10.1″. Their different spectral classes — F8 and G5 — mean that close attention may reveal differing colors.

Several other double stars sit in or near Hydra’s head, including STF 1255 and STF 1290. The former is easy to split, but the latter is more challenging than Epsilon.

Sunrise: 7:22 A.M.

Sunset: 4:54 P.M.

Moonrise: 12:08 P.M.

Moonset: 12:45 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (60%)

Tuesday, January 11

The Moon passes 1.5° south of Uranus at 6 A.M. EST. By sunset this evening, they are a respectable 5.7° apart high in the southern sky, making it easier to pick up Uranus’ dim light once darkness falls.

To locate the distant ice giant, which is now southwest of the Moon, look for 2nd-magnitude Hamal, the Ram’s brightest star. Drop 10.7° to its lower left (southeast) to spot Uranus’ magnitude 5.8 glow in binoculars or a telescope. The planet’s disk spans nearly 4″ and should appear like a “flat,” greenish-blue star. Uranus currently sits some 19.4 astronomical units (AU) from Earth, where 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance. That means sunlight reflecting off its surface must travel back through the solar system for nearly 3 hours to reach our eyes.

Asteroid 3 Juno is in conjunction with the Sun at 5 P.M. EST tonight.

Sunrise: 7:21 A.M.

Sunset: 4:55 P.M.

Moonrise: 12:33 P.M.

Moonset: 1:46 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (69%)

Wednesday, January 12

The Moon passes 1.2° north of dwarf planet 1 Ceres at 7 P.M. EST. You’ll find them in the eastern sky after dark, hanging out with the familiar figures of Gemini, Orion, and Taurus. Our satellite sits about 5° south of the Pleiades open cluster tonight, with Ceres just to its right on the sky. Because they are so close, it may be challenging to pick up Ceres’ 8th-magnitude glow amid the bright moonlight. If you have trouble, don’t worry — the dwarf planet will spend all month in nearly the same spot, while the Moon will quickly move on. In fact, Ceres is just days away from reaching its stationary point on the sky, after which it will make a tight turnaround and begin sliding northeast against the background stars.

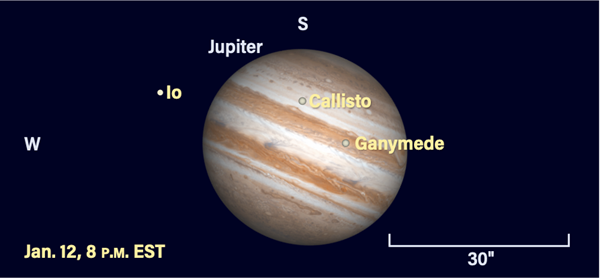

But the sky has more in store for us tonight than just this close encounter: earlier in the evening, you’ll want to look west to catch a rare double transit as Jupiter’s moons Callisto and Ganymede slide in front of the giant planet. The event begins at 5:22 P.M. EST, when Callisto slips onto the disk from the east. Ganymede follows at 6:50 P.M. EST. As you watch — and while the planet slowly sinks — you’ll see Ganymede start to catch up to Callisto. This is because Ganymede’s orbit is smaller and closer to the planet, so it moves faster across the sky. Those in the western U.S. will be able to catch a third moon, Io, closing in from the west and slipping behind Jupiter’s disk at 8:36 P.M. EST. West Coast observers will also be able to watch Callisto’s transit end at 6:45 P.M. PST; Ganymede slides off the disk at 7:24 P.M. PST.

Sunrise: 7:21 A.M.

Sunset: 4:56 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:00 P.M.

Moonset: 2:47 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (77%)

Thursday January 13

Asteroid 7 Iris reaches opposition at 4 P.M. EST, meaning it will be visible all night long. It’s glowing at magnitude 5.8 — well within reach of binoculars or a small scope — in eastern Gemini, rising as the Sun sets. To find Iris, first locate Lambda (λ) Geminorum, which shines at magnitude 3.6. Scan 4.5° east of this star to land on the reflected light from this large, 124-mile-wide (200 km) main-belt asteroid.

Also in the evening sky is a not-to-be-missed close encounter between Mercury and Saturn. At sunset, the two are 3.4° apart in northern Capricornus. Mercury is now magnitude 0.1, a bit brighter than magnitude 0.7 Saturn.

Once the Sun has safely set, zoom in on each planet with a telescope to enjoy Saturn’s stunning ring system, which stretches some 35″ on the sky. Lucky observers may also spot its largest moon, Titan, 2.5′ east of the planet’s center tonight. Meanwhile, Mercury spans 8″ through a telescope and appears just 29 percent lit. The solar system’s smallest planet comes to a halt, sitting stationary against the background stars at 8 P.M. EST. It will now begin reversing course and pull away from Saturn over the next several days.

Sunrise: 7:21 A.M.

Sunset: 4:57 P.M.

Moonrise: 1:32 P.M.

Moonset: 3:48 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (85%)

Friday, January 14

The Moon reaches apogee, the farthest point from Earth in its orbit, at 4:26 A.M. EST. At that time, our satellite will be 252,155 miles (405,804 km) away.

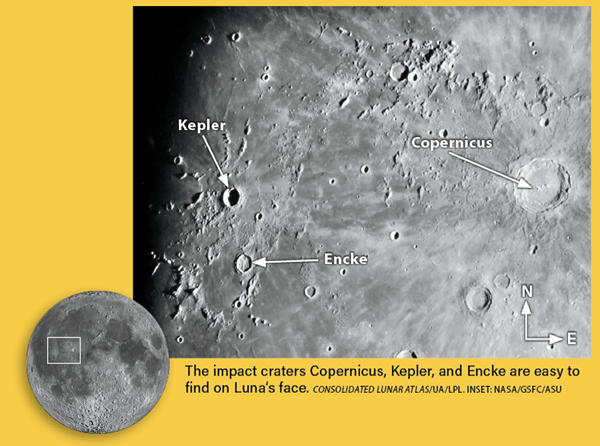

Now that the Moon is several days past First Quarter, let’s check in and see how its appearance has changed. Turn your telescope on its face this evening and look in the lunar west (east on the sky) for the large, dark Oceanus Procellarum. On its eastern flank, near the center of the lunar disk, is the prominent crater Copernicus. West of that is the smaller, sharply defined bowl of Kepler. A bit to Kepler’s south is the similarly sized Enke, which has a flatter, brighter floor, making it appear shallower and more ringlike. That’s because Enke is filled with ejecta from Kepler’s creation, meaning it’s older than the younger, deeper feature.

Keep returning to this region for the next few nights and you’ll see Enke all but disappear under the changing Sun angle as lunar noon (Full Moon) approaches.

Sunrise: 7:21 A.M.

Sunset: 4:58 P.M.

Moonrise: 2:09 P.M.

Moonset: 4:48 A.M.

Moon Phase: Waxing gibbous (91%)