Like a pop fly in baseball rounding the top of its arc, Machholz appears to slow this month. From Earth’s perspective, it lies almost straight up from the north pole, giving us a good line of sight to its tail, which points away from the Sun. You should see two tails. A slightly bluish tail of ionized gas blowing straight out in the solar wind of charged particles, and a yellow-white tail arcing gracefully as ejected motes of dust begin tracing their own orbital arcs. The comet’s tails should become easier to see this month because they are leaving the brighter background of the Milky Way in Perseus and Cassiopeia.

Saturn and its glorious rings dominate the evening sky. Look for the bright, steady, pale-yellow “star” halfway up in the east as the sky grows dark. If Earth’s atmosphere is not too turbulent, crank up the magnification to take a close look at the shadow of the planet on the rings. The shadow is now on the opposite side from where it was a couple of months ago and growing wider week by week, the same way your shadow gets longer

in the afternoon.

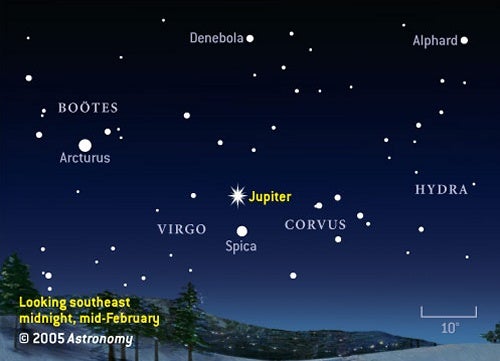

Planetary enthusiasts have kept giant Jupiter and its enticing cloud features under scrutiny ever since it returned to view last October. Now that the planet rises before midnight, thousands more observers will join in. Will the Great Red Spot finally begin a comeback to recapture its name? Are there any new white ovals? Backyard observers return to Jupiter every year because it always shows plenty of detail, but the unexpected remains one of the planet’s strongest drawing cards.

Although the Moon lies much closer to Earth than Jupiter, perspective makes it appear to have a close encounter with the planet the morning of January 31. Jupiter lies about two to three lunar diameters from the Moon in the 2-o’clock position relative to the lunar terminator.

What happens when the Moon passes in front of a red supergiant star? On the morning of February 4, around 5h Universal Time, those in southern Scandinavia and Eastern Europe will find out as the Moon hides Antares. Next month, and in May, observers in North America have the chance to see beautiful dark-sky occultations of Antares.

Most stars appear as mere pinpoints through a telescope. Yet bloated red supergiants like Antares are so huge that when the knife edge of the Moon cuts across them, they disappear in the blink of an eye instead of instantaneously. That may not sound much slower, but it is noticeable.

A delicate, thin crescent Moon returns to the evening sky February 9. Sighting this young Moon, just 1 day old, should mark a personal best for most newcomers. The next evening, the crescent appears higher and more visually appealing, with the Moon’s dark face lit by earthshine.

Last month, we examined the California Nebula (NGC 1499) in Perseus, a classic example of an emission nebula. A hot, massive star floods space with ultraviolet light, which strips electrons from atoms. When these so-called ionized atoms settle down from this excited state, many emit light in the visible part of the spectrum.

But what if the star isn’t that hot? Its light still can scatter off the gas atoms and dust, in much the same way light scatters off a fog bank on Earth. The most famous reflection nebulae are the wisps surrounding the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus and the wonderful blue and yellow clouds around Rho Ophiuchi near Antares.

Another interesting, if less well-known case, lies in Perseus. IC 348 resides just south of 4th-magnitude Omicron (ο) Persei. The nebula appears as an ill-defined circular patch of light surrounding a pair of stars. About a dozen stars clump around these two, probable remnants of a communal star cluster formed from the cloud. With a diameter of 6′, the brightest patch of IC 348 is relatively small, similar in apparent size to the bright galaxies of the Virgo cluster, so it’s okay to bump up the power to get a good look.

IC 348’s low contrast makes it most appropriate for dark-sky viewing. One trick to try: Move the scope south or southeast to put the bright stars just outside the field of view. Let your eye readjust, then come back slowly toward the nebula. If conditions are right, you’ll see the background has a faint, milky glow on it.

A lake of blackness

You might think if no star lies near or shines bright enough to light up the dust and gas, the interstellar medium would be transparent. Not so. Instead, like clouds backlit in deep twilight, interstellar clouds absorb light from beyond. If they contain enough stuff, visible light can’t get through.

Swing your telescope 1° northeast of IC 348, and you’ll see all the faint stars have disappeared. This is B5, cataloged by pioneering astronomer E. E. Barnard with his wide-angle photographs of the Milky Way. You may need to use medium power (100x) to pull in the fainter stars on B5’s periphery to make the nebula stand out a bit more.

Slew your scope back through Omicron, and you’ll dip into another dark expanse, B4. Keep moving your scope around, trying to follow the path of obscuration. If you continue west, you might run into NGC 1333, a modestly bright reflection nebula.

Doubling up

A couple degrees north of the IC 348 complex lies the double star 40 Persei. This very uneven pair sports components glowing at 5th and 10th magnitude. They serve as a departure point to another double, S425, which makes a nice test object for a 4-inch scope. Both stars glow at magnitude 7.6 with a mere 1.8″ separation, half the gap of summer’s famous Double Double in Lyra. For the best view in small instruments, pump up the power to 50x per inch of aperture.

The solar system’s fleeting innermost planet makes a brief appearance in the evening sky in the final days of February, but Mercury will put on a much better show in March. On February 28, it shines at magnitude –1.5 and stands 5° above the western horizon 30 minutes after sunset. You will need an exceptionally clear horizon to spot the planet when it lies this low, and binoculars certainly will help the quest. Its visibility improves in early March, when a crescent Moon skims by.

While Earth’s nightly rotation carries Saturn to the west, the combined motions of Earth and Saturn in their orbits currently causes Saturn to move west relative to the background stars, the reverse of its normal easterly motion. Saturn passed opposition in January and, consequently, Earth now is overtaking the ringed planet.

During February, Saturn lies an average distance of 8.2 astronomical units, or 760 million miles, from Earth. Saturn’s 75,000-mile-wide disk reaches 20″ across when viewed from here, and its ring system spans 46″ at its widest.

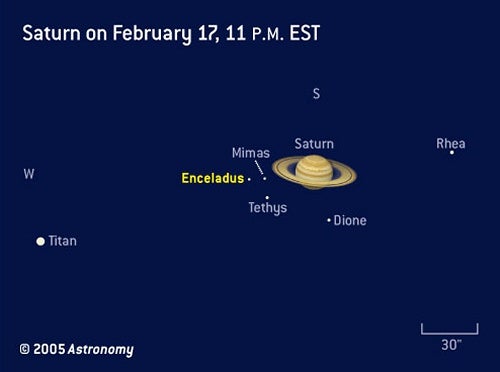

Telescope owners have plenty of tempting targets this month. The brightest of Saturn’s retinue of 37 moons — at last count — shows up easily: Titan could be spotted with binoculars if Saturn weren’t so close. Keen eyes still might succeed at this feat when Titan lies at greatest elongation east or west of the planet. On February 3 (west), 11 (east), 19 (west), and 27 (east), Titan lies just under 4′ from the center of the ringed planet. Try spying the moon with binoculars mounted on a steady tripod.

Through a telescope, you can track Titan easily throughout its whole 16-day orbit of Saturn. The moon passes north of Saturn February 15 and south both February 7 and 23. Even a low-power eyepiece can pick up this moon.

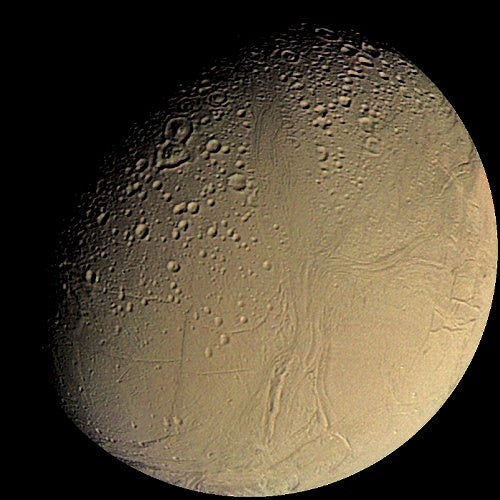

Higher magnification allows you to spot some of the moons closer to Saturn. Using a higher power reduces the glare from Saturn by spreading its light over a larger area. Mimas scampers around the planet in just 1 day and glows at magnitude 12.9. Enceladus completes an orbit every 1.4 days and glows at magnitude 11.7. Cassini makes its first close approach to Enceladus February 16/17. Images taken by the Voyager spacecraft revealed intriguing geological features on this moon, so planetary scientists eagerly await the first close-ups from Cassini’s more-powerful camera.

A trio of 10th-magnitude moons awaits your discovery between the orbits of Enceladus and Titan. Tethys takes 1.9 days to circle Saturn, Dione 2.7 days, and Rhea 4.5 days.

Outside Titan’s orbit lies Hyperion, Iapetus, and Phoebe, although Iapetus is the only one visible through a small scope. Its curious nature — bright material covers half the moon, and dark material coats the other half — causes it to vary in brightness by 5 times as it orbits Saturn. You’ll find it fading during February as it moves from western elongation to east of the planet.

Jupiter’s appearance through a telescope reveals a disk 41″ across, almost as wide as Saturn’s rings viewed through the same scope. Its brilliant disk can hide some low-contrast atmospheric features, as can a poorly collimated Newtonian or Cassegrain telescope. The best views always come when your telescope is well-collimated — and when the tube has settled to the outside air temperature. With these precautions, your planetary viewing will take on added interest.

Jupiter’s atmosphere shows dynamic changes and rotates at two different speeds. The equatorial region completes one full rotation in 9 hours and 50 minutes, while higher latitudes take about 5 minutes longer. The churning that results creates plumes of material around the outer edges of the two dark equatorial belts.

Jupiter’s four Galilean moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — can be seen easily through any telescope. Indeed, Galileo first spotted these worlds orbiting Jupiter back in 1610. Each night, you’ll notice the moons in different positions relative to Jupiter. Often one or two, and rarely three, disappear behind or in front of Jupiter. Such occultations and transits are fascinating to watch, especially when a moon’s shadow falls as a jet-black dot on the jovian atmosphere during a transit.

You’ll have to wait until almost 5 a.m. to see another planet appear. Mars climbs above the southeastern horizon in the company of the stars of Sagittarius at 4:40 a.m. local time February 1 and half an hour earlier by the 28th. The Red Planet is far from spectacular through a telescope now, but it will be later this year. It currently lies 180 million miles from Earth. The tiny globe spans a mere 5″ and shines at magnitude 1.3.

The morning of February 5, you’ll find Mars 5° above a thin crescent Moon. Although Mars won’t reveal much surface detail this month, it passes near a few nice deep-sky objects in the richest part of the Milky Way. Mars slides between the Lagoon and Trifid nebulae (M8 and M20, respectively) the morning of February 7. Try to catch the trio early, before the fast-approaching twilight washes out the nebulae. On February 18, Mars lies 0.3° north of the globular cluster M22, making a fine photo opportunity for rich-field telescopes. By month’s end, Mars stands east of the handle of the Teapot asterism in Sagittarius.

Few sights inspire backyard stargazers more than seeing the Moon pass near another prominent object. It happens most frequently with the bright planets and a handful of 1st-magnitude stars because the Moon returns to the vicinity of each once a lunar month. The best such events in February are gibbous Moon appearances near Jupiter (the 27th) and Saturn (the 19/20th) and a crescent Moon appearance near Antares (the 4th).

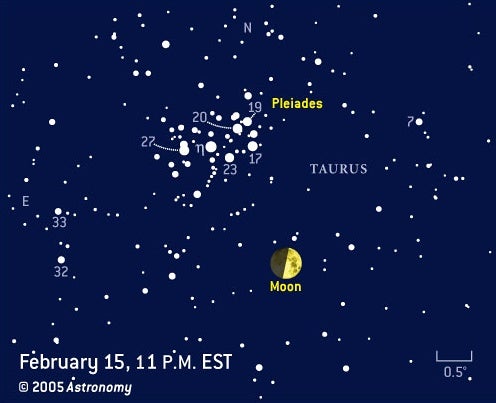

Much less often, the Moon makes a nice pass by a bright deep-sky object. These events are rare because only one deep-sky object — the Pleiades star cluster (M45) — combines the two essential ingredients: It shines bright enough to stand up to the Moon’s brilliance, and it lies close enough to the Moon’s path across the sky that our natural satellite occasionally comes near. Add in the fact that the cluster isn’t so bright that it can rival a gibbous or Full Moon, and it’s a wonder these close conjunctions aren’t even more uncommon.

When the First Quarter Moon passes 1.2° south of the Pleiades the night of February 15/16, it marks the objects’ first close encounter since the early 1990s. The long drought stems from the Pleiades’ position relative to the lunar orbit. The cluster lies at a declination of 24°, on the northern part of the Moon’s orbital path. For the past dozen years, the Moon has been well south of the Pleiades each time it made its monthly pass.

The good news: The Moon and Pleiades will be close each month for the next few years. The slow shift of the lunar orbit means once these events begin, they keep going for a good while. Later this year, the Moon actually starts to cross in front of the cluster. The two won’t always appear real close, and at least half the time, the Moon’s brightness will overwhelm M45. (The best views of a waxing crescent Moon near the cluster will come on spring evenings.) It’s a series of events you won’t want to miss.

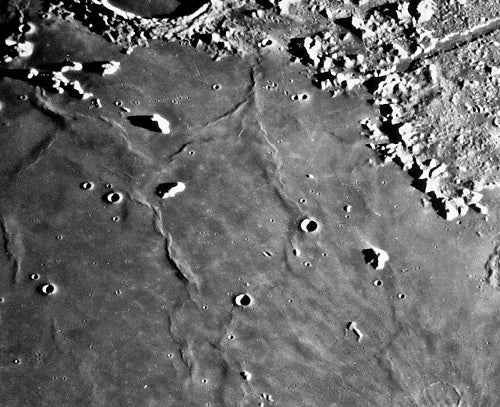

Two huge mountain peaks lie south and southeast of Plato, a large, prominent crater in the northern part of the Moon’s nearside. The two mountains join numerous others scattered across the flooded plain of Mare Imbrium. Mount Pico, closer to Plato, rises almost 8,000 feet from the lava plain. Slightly smaller Mount Piton pushes some 7,400 feet high.

Between the two peaks and nearer Piton, you can find a small crater called Piazzi Smyth. East of Piton lies the crater Cassini (see “Meteors and moons,” November 2004).

The peaks of Pico and Piton catch the Sun’s rays before the surrounding landscape and can, on occasion, appear as brilliant, star-like points beyond the advancing terminator. This occurs approximately 8 days after New Moon, or around First Quarter phase. Both mountains have complex peaks with ridges that dramatically alter their appearance as the Sun rises.

Prominent mountain ranges lie near both peaks. North of Mt. Piton lie the lunar Alps, named after the magnificent range in Europe. West of Mt. Pico are the Teneriffe Mountains, a cluster of peaks that dot the northern shore of the Imbrium basin.

Visible to the naked eye from dark sites, Comet C/2004 Q2 (Machholz) heads for the pole this month. Now that it is moving away from the brighter background sky of the Milky Way in Perseus and Cassiopeia, this round fuzzball should be easier to see, despite having faded slightly from its peak brightness in January. (The 5th-magnitude comet gave us a nice wide-field photo-op between January 28 and 31, when it crossed an area of glowing gas clouds.)

The first 10 days of February should be best because the Moon’s light won’t bathe the evening sky. Sweep with binoculars to the upper right of Cassiopeia’s M outline. If you’re having trouble seeing the comet, it may be that you’re not waiting long enough to dark-adapt — it typically takes more than 20 minutes before your eyes fully adjust to the darkness.

There are no easy star patterns to latch onto in this rather sparse area of northern Cassiopeia and Camelopardalis unless you’re a variable star observer. Comet Machholz should eclipse the well-known eclipsing binary RZ Cassiopeiae the evening of February 7. In an eclipsing binary system, the fainter star regularly moves in front of the brighter one, causing the pair to dim. In the case of RZ Cas, the pair fades from magnitude 6.2 to 7.7 in about 2.5 hours.

On the nights of February 13 and 14, C/2003 K4 lies less than an apparent Moon-width east of the large planetary nebula NGC 1360. Unfortunately, the nearby Moon will lighten the sky.

A third comet graces the predawn sky. Comet C/2003 T4 (LINEAR) should brighten to 8th magnitude or so this month, becoming a pleasant telescopic sight. In mid-February, it will be nicely framed by the Dumbbell Nebula (M27) in Vulpecula and M71, a loose globular star cluster in Sagitta.

High-numbered rock

Usually, brighter asteroids were discovered (and hence numbered) before fainter ones, so it’s a rare treat to be able to track one with a high number. The one designated 532 Herculina has a modestly eccentric orbit, and this year, it lies near its perihelion, or closest point to the Sun, at the same time it reaches opposition. That’s why it appears brighter than normal.

Spanning 129 miles, Herculina glows at magnitude 9.2 in early February. It floats in front of Gemini, quite close to the twin bright stars Castor and Pollux and slightly north of the even brighter Saturn. A second asteroid, 8 Flora, also lies nearby. It glows at 9th magnitude some 5° southwest of Herculina.