Although Jupiter shines brightly, Venus dazzles in comparison. And while Venus gleams a pure white, Jupiter shines a few shades toward pale peach. Watch how their colors deepen toward orange, and even red, as they descend through Earth’s thick lower atmosphere.

The planets appear closest to each other September 1. Nevertheless, you should start looking during the last week of August to see Venus climbing away from the Sun while Jupiter slides in. Mark your calendar for September 6, when the waxing crescent Moon joins the duo to create a stunning trio. View the gathering with your naked eyes and binoculars. With this optical aid, you should see a fainter sparkle directly below Venus and to the Moon’s left: the bright star Spica.

Don’t miss this conjunction — the next nice one between the two brightest planets happens in February 2008.

The Moon hides in the Sun’s glare at the start of September, then returns to form a lovely trio with Venus and Jupiter the evening of the 6th. Look for the gray shading on the dark side of the Moon. Astronomers call this light earthshine because the Moon is returning sunlight that has reflected off Earth.

Note the Moon’s path over the next several evenings. It crawls low across the south until it becomes Full the night of September 17 — the Harvest Moon. Four nights later, it joins Mars near the Pleiades cluster (M45).

Saturn, the bright yellowish “star” in the east as dawn breaks, also goes by the name of the Greek god Cronus. Across the millennia, Cronus has been confused with Chronos — father time. It doesn’t help that Saturn takes 29.5 years to complete a full circuit of the background sky, providing a handy measure of time’s passage. Indeed, it’s a celestial anniversary of one of this column’s authors, Alister Ling: “I first laid eyes on Saturn in November 1975, when it made a nice triangle with Castor and Procyon. I’ll never forget the view through my new 4.5-inch scope, aimed between the trees from the sidewalk. I’m sure it will stir more memories when I see Saturn in Cancer again.”

The distant gas-giant planet Uranus reaches its peak the night of August 31/September 1. At magnitude 5.7, it glows brightly enough to be spotted with the naked eye from a dark site. Find it first with binoculars next to the 4th-magnitude star Lambda (λ) Aquarii.

Barnard’s dim galaxy

Far from the crowded core of our expansive galactic empire lie dozens of fainter dwarf colonies. Instead of the hundreds of billions of stars that constitute a major galaxy like ours, most dwarfs contain only a few million. Astronomers are still trying to piece together the puzzle of the dwarfs’ origin and evolution. In some cases, the galaxies have already suffered a passage through the Milky Way that robbed them of their gas and flung their stars into long, trailing arcs.

Discovered visually through a 5-inch refractor by famed observer E. E. Barnard in 1884, this modestly large, elongated patch of light can be teased out of the background sky only under the best haze-free conditions. Get well away from city skyglow, and seek it out at the beginning or end of September, when moonlight does not interfere. The galaxy’s long axis spans more than 10′, so use your lowest-power eyepiece to get a nice wide field of view. (In comparison, the Moon covers 30′ of sky.)

Start your search with the chain of stars that includes 54 (a wide double) and 55 Sagittarii, then slowly sweep north and east a bit less than 2°. Because the human eye is fairly sensitive to motion, you probably will find this dwarf galaxy easier to see if you nudge the telescope a bit.

NGC 6822 appears so diffuse, it tends to disappear into the background when viewed with a large telescope at high power. However, you’ll need the larger light grasp of a big scope to pick out some of its associated gas clouds. The brightest emission nebula in the galaxy is IC 1308, attached to the northeastern flange of the glow. Both UHC and OIII nebula filters will help you see it, but remember to use a dark hood to conserve all the photons coming through the eyepiece.

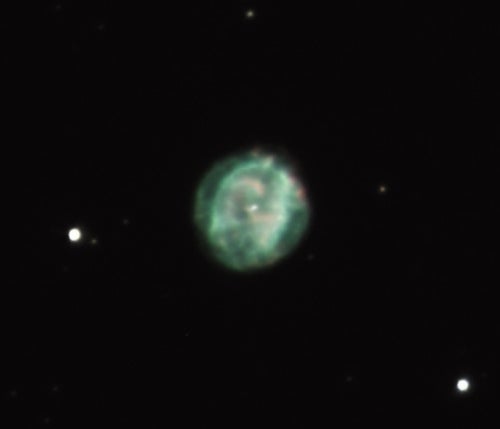

You’ll have a much easier time finding NGC 6818, a planetary nebula in our own galaxy that lies just 0.7° north-northwest of Barnard’s Galaxy. Nicknamed the Little Gem Nebula, it looks like a 10th-magnitude star that seems a little “flat” when viewed at low magnification. Pump up the power to see a circular, gray-green disk of light 22″ across. From our earthbound perspective, this appears barely wider than the ball of Saturn, but in reality, it spans about half a light-year.

Near the end of a star’s life, it puffs off its outer layers, which glow from ultraviolet radiation emitted by the white-hot core that remains. William Herschel, who coined the descriptor “planetary nebula” for these objects, discovered the Little Gem August 8, 1787. A 6-inch scope will pick up NGC 6818 from a suburban backyard.

Early evening September 1 provides the setting for a dramatic encounter between Venus and Jupiter. Normally, Jupiter’s brilliance is enough to attract attention, but this time, it looks dim compared with Venus. Venus dazzles at magnitude –3.9. Jupiter, which lies just 1.2° above Venus, appears nearly 10 times fainter, shining at magnitude –1.7. Watch as the sky darkens, turning from orange through aqua blue to deep blue, and the brilliant planets sparkle like a pair of jewels.

A great way to remember the scene is to take a photograph. Set up your camera on a tripod, and use the self-timer or a cable release to fire the shutter. (This avoids jitter created by manually pressing the shutter.) The best pictures contain a scenic foreground object. When placed against the bright evening twilight, the foreground will form a beautiful silhouette.

Although the two planets appear close together in our sky, they reside at dramatically different distances from Earth. Venus lies 105 million miles away, while Jupiter comes in at a distance of 577 million miles.

On September 6, a crescent Moon joins the planets, now separated by 5°. This evening, the Moon sits 3° south of Jupiter and 4° west of Venus. You should also see a 1st-magnitude star 1.8° below Venus. This is Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo the Maiden.

Venus continues to pull away from Jupiter, and by the 9th, both lie just shy of 5° from Spica. For the rest of September, Jupiter sinks lower in the west and sets earlier each night. Twilight begins to drown it out toward the end of the month. Venus remains visible, hugging the southwestern horizon. It passes 2° south of Zubenel-genubi (Alpha Librae) on the 24th. Through a telescope, Venus grows to 18″ across, while its phase shrinks to 65-percent lit by month’s end.

The last evening conjunction between Venus and Jupiter occurred in June 2002. However, in terms of their altitude, this month’s is the best evening conjunction since February 1999. The next good conjunctions between these two planets occur in the morning sky in February 2008 and in the evening sky in November 2008.

Glowing at magnitude 7.9, Neptune proves much easier to see, although you’ll still need a telescope to view its tiny 2.3″-diameter disk. The outermost gas giant reached its peak at opposition last month and remains well-placed for viewing. You can track its slow motion with binoculars as it treks westward through Capricornus the Sea Goat. It lies approximately midway between 29 and Theta (θ) Capricorni, edging closer to Theta.

Neptune’s inner cousin, Uranus, reaches opposition the night of August 31/September 1. You can find it between 3° and 4° southwest of the 3.7-magnitude star Lambda (λ) Aquarii. This star lies midway between the lower-right star of the Great Square of Pegasus, 2nd-magnitude Markab, and the 1st-magnitude star well south of it, Fomalhaut.

Uranus glows at magnitude 5.7, making it an easy binocular target that’s even visible to the naked eye under a dark sky. The challenge comes in identifying which faint point of light is the planet. Either use a good star chart with Uranus’ position marked on it or draw the field of view over 2 to 3 nights. Uranus will betray itself by its slow motion. Alternatively, aim your scope at the suspected planet; at medium power, you should see its 3.7″-diameter blue-green disk.

Mars gleams so brightly and with such a distinct ruddy hue, you won’t confuse it with any other object. On September 21, Mars stands 5° south of a waning gibbous Moon. The next night, the planet crosses into Taurus. By the end of September, Mars lies less than 10° from the Pleiades star cluster (M45).

Mars closes on Earth fast and brightens considerably this month, climbing from magnitude –1.0 to –1.7. It easily bests the brightest star in this vicinity, Aldebaran. For those with telescopes, Mars’ phase and angular diameter both increase this month. The disk spans 14″ and appears 87-percent illuminated September 1. These numbers climb to 18″ and 93-percent lit by month’s end.

The Red Planet is better placed in the sky for observing than during its historic opposition 2 years ago. Although it won’t come as close to Earth as in 2003, its much higher altitude will greatly benefit observers in the Northern Hemisphere.

The south pole of Mars currently tilts in our direction, giving us a good view of the south polar cap. However, the cap will shrink throughout the apparition as Mars’ southern summer continues.

Keen-eyed observers occasionally spot clouds on Mars. September is a good month to watch for orographic clouds near the Tharsis region. Such clouds form when mountains force moisture-laden air to rise, creating clouds on their downwind side. With massive peaks like Olympus Mons and the other Tharsis volcanoes, such clouds may become visible. You can improve their visibility by using blue or violet eyepiece filters to enhance their contrast.

Mars will make its closest approach to Earth at the end of October and reach opposition November 7.

Saturn lies near the Beehive star cluster (M44) during September. Between the 10th and 20th, the two objects appear together in the same low-power field of view. On September 28, a waning crescent Moon joins the scene. Saturn rises more than 2 hours before the Sun in early September and, by month’s end, appears high in the east well before twilight begins.

Innermost Mercury makes a fine appearance in the early morning sky during the first week of September. On the 4th, it lies 1.1° north of Regulus, Leo’s brightest star, although the latter is barely visible in the brightening twilight. At magnitude –1.4, Mercury shines much brighter than Regulus.

By the 9th, Mercury rises only 40 minutes before the Sun. Although it shines brightly at magnitude –1.6, its visibility becomes limited against the glowing twilight. After this date, it will be hard to follow.

A pair of Aurigids

September traditionally ranks low on most meteor observers’ calendars. Certainly in comparison to August’s high activity, September tends to be overlooked. The month’s many minor showers all tend to be under-observed.

With a Full Moon occurring during the third week of September, meteor watchers should get their best views early in the month. The Alpha Aurigids, a minor shower that typically produces a meteor every 10 minutes, remains active from August 25 to September 8. It peaks, if that phrase can be used for such a minor shower, September 1.

The meteors rank among the fastest — slamming into Earth’s atmosphere at 41 miles per second. During the past century, backyard observers have recorded three Alpha Aurigid outbursts (in 1935, 1986, and 1994), when rates reached 1 meteor nearly every 2 minutes. Although astronomers don’t anticipate such activity this year, the possibility can’t be discounted.

Spotlight on Hadley

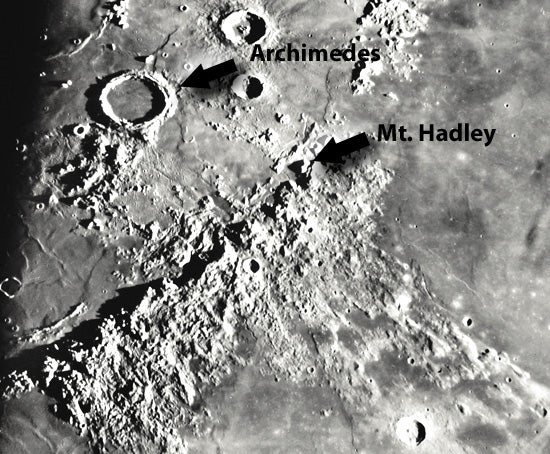

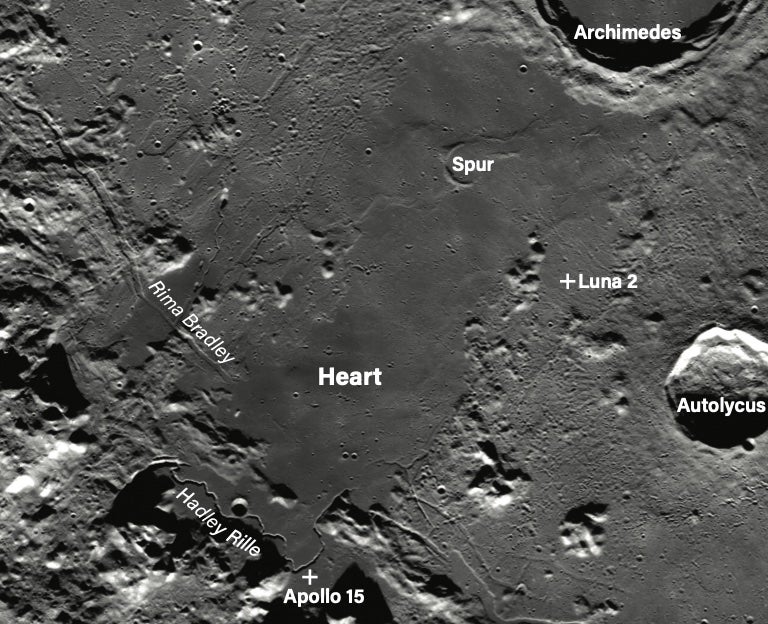

On July 30, 1971, Apollo 15 astronauts Dave Scott and Jim Irwin landed near a rille located not far from Mount Hadley. Although the lunar lander is far too small to be seen using telescopes on Earth (or in orbit, for that matter), the region provides plenty of nice features to observe with a backyard telescope. Mount Hadley lies near the northern end of the lunar Apennine Mountains. Three distinctive craters reside nearby on the Mare Imbrium plain: Archimedes, Aristillus, and Autolycus.

To find the region, first center these three craters in a low-power eyepiece. Then locate a small lava plain to the east of Archimedes, bounded by mountains on the eastern side, and switch to a higher-power eyepiece. Set within the mountain range itself is a single small crater, Conon, which spans 14 miles. The area to its north, the small lava plain noted earlier, is called Palus Putredinis (or Marsh of Decay).

Under good seeing conditions, you should see a complex network of rilles here. The Sun rises over the region September 11, providing sharp shadows and exquisite views.

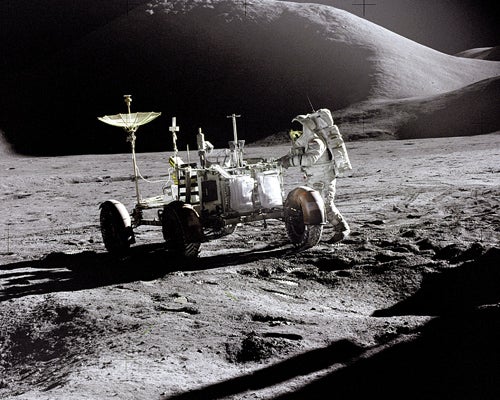

Apollo 15 introduced the lunar rover, helping to make this one of the most exciting visits to the Moon. The rover spent two of its three excursions exploring Hadley Rille.

Deep Impact’s legacy

A year ago, it looked as though we were headed toward a famine of bright comets, leaving only faint, challenging fuzzballs for dark-sky enthusiasts. Then one night, Don Machholz discovered a comet that would give us 6 months of good views. Now, as we head into the final few months of 2005, no comet brighter than 11th magnitude looms on the horizon. Let’s hope we get lucky again.

Comet 161P/Hartley-IRAS should glow around 11th magnitude this month. It remains visible all night between the handle of the Big Dipper and Arcturus in Boötes.

Because moonlight doesn’t affect digital imagers as much as it does visual observers, see if you can capture 12th-magnitude Comet 37P/Forbes as it slides by two globular star clusters north of the Teapot asterism in Sagittarius. The comet passes 8th-magnitude NGC 6544 September 10 and 9th-magnitude NGC 6642 the 20th.

The solar system’s largest asteroid, 1 Ceres, measures 595 miles across. Not surprisingly, it was the first asteroid to be discovered. Although it currently plies the modestly rich star fields of Libra the Scales, Ceres glows at 9th magnitude, so it remains brighter than the typical background star in this area.

Although watching an asteroid blot out the light from a distant star for a few seconds used to be a rare event, it now occurs almost monthly. No, such events aren’t becoming more common, we just can predict them for fainter stars and asteroids thanks to improvements in star catalogs, accuracy of asteroid orbits, and computer speed. Steve Preston’s web site, www.asteroidoccultation.com, contains an easy-to-browse list of upcoming events with maps showing the area and time. Thanks to his finder charts that zoom in on the exact location, it’s a snap to get ready.