This was the big one.

Nearly seven years after totality crisscrossed the U.S. in August 2017, the Moon once again slipped in front of the Sun in the skies above North America on April 8, 2024. Making landfall in Mexico, the Moon’s shadow swept across the continent, through the heart of the U.S. into New England and on to Canada. In the U.S. alone, over 31 million lived in the path of totality — two and a half times more than in 2017. It would not be an exaggeration to say that this was the most anticipated celestial event this magazine has seen since the return of Halley’s Comet in 1985–86.

To cover the eclipse, the staff of Astronomy were scattered along the path of totality. Here’s what we saw — and heard, and felt.

An eclipse victory at Love Field – Dallas, Texas

Weather is a one-day event. For all the analysis of trends, of where clouds or Sun will mark the landscape, anything can happen on any given day. In Texas, the weather prospects for the Great North American Eclipse looked bleak. For days, it seemed a sure thing that storms, or at least thick clouds, would plague the Dallas region. And then came eclipse day.

My journey this year was centered on Dallas Love Field Airport, best known in recent history as the landing site for John F. Kennedy’s ill-fated 1963 trip to the city. But the airport is still active and hosts a fantastic collection of aircraft and aviation artifacts in the Frontiers of Flight Museum. For the eclipse, the museum’s team, led by President Abigail Erickson-Torres and facilitated by their energetic director of education, Rosalie Wade, assembled a wonderful day of programming that welcomed some 2,500 members of the public onto the grounds.

We also partnered with our good friends at Celestron, who turned out in force. Corey Lee, Kevin Kawai, Ben Hauck, Stephanie Schroeter, and others were on hand, setting up telescopes the day before the eclipse. And that wasn’t all: Partners from The Weather Channel were also there broadcasting live, with meteorologist Alex Wilson taking the lead on camera and a big team led by producer Mike Jenkins coordinating the whole process. It was an extreme pleasure working with Wilson. She is such a smooth pro that it was effortless to talk about the science, the observations, and the meaning of it all as we prepared to look skyward and witness the alignment of worlds.

But when I drove to Love Field at 5 a.m. on eclipse day, it looked like a washout. I had experienced a dozen total eclipses before this one, two of them underneath a solid blanket of clouds. Believe me, that’s not a good way to see an eclipse.

As dawn broke, the sky was still sketchy and the forecast less than great. At one point, The Weather Channel proclaimed that the place with the best chances for clear skies was Maine. Mexico seemed troubled too. As we looked to the south, past Parkland Memorial Hospital on the horizon, walls of clouds seemed to be destined to move our way as the morning continued.

I spent the waning moments of pre-eclipse in the museum auditorium with a packed house, explaining everything everyone needed to know to view and photograph the eclipse. When I walked out into the field again at noon, with first contact approaching, the situation had changed. Clouds were less dense, and hope appeared. Amazingly enough, as we awaited first contact, we had significant holes and could get a good view of the Sun, some 60° high in the sky. We would see the start of things, at least.

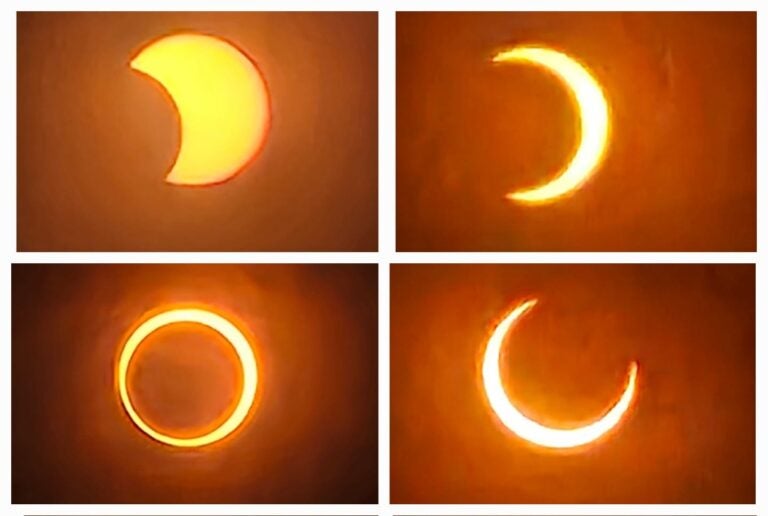

As always happens, people screeched out in joy as the first little bite out of the Sun’s disk became visible. Although we’ve had precise knowledge of the motions of the solar system since the days of Johannes Kepler, it always seems a bit like magic to many people when we count down by the second and an eclipse starts, right on schedule.

Although thick clouds were visible way down to the south, we had a long, vertical corridor of clear sky that seemed to favor us as totality approached. It dawned on us that we were going to defy the odds and see this thing. With a fresh burst of excitement, Wilson and I narrated much of what was happening on The Weather Channel. The rapid darkening of the sky during the final moments before totality always amazes, and we felt rapid cooling of the air, too. And then: the diamond ring! Glasses off! We had totality — and it looked spectacular!

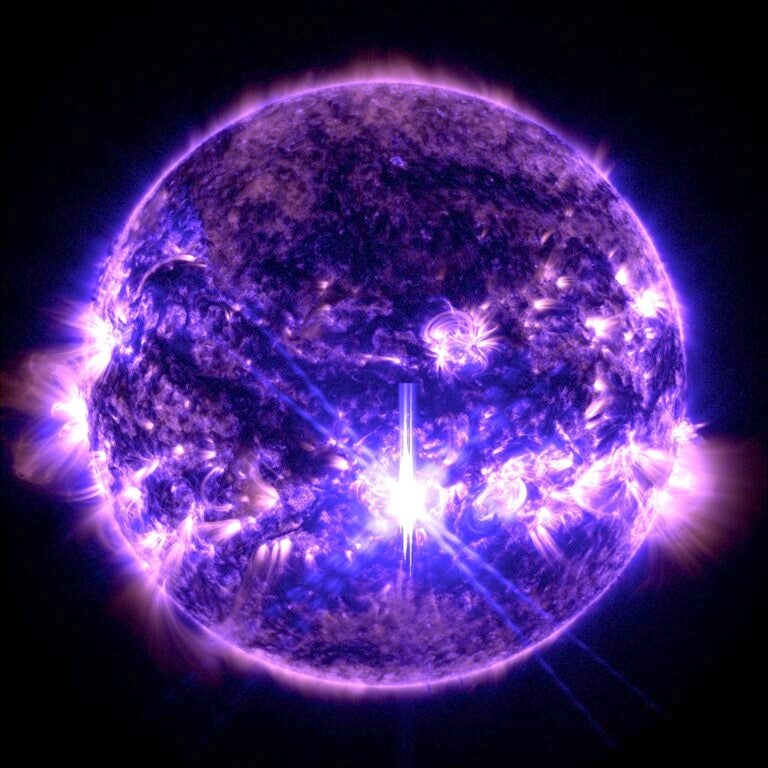

Our Love Field site experienced 3 minutes 51 seconds of totality, and we saw the whole thing perfectly. The corona seemed large, flowerlike, and with some pretty good brushes and rays, too, expected from the current cycle of solar activity. We had some nice prominences as well, especially one at bottom right (as we faced south) that was incredibly bright near the end of totality. Venus popped out immediately and Jupiter too, after a bit of cloud passed it. We did not expect to see Comet Pons-Brooks, nor waste time with binoculars searching for it. The chromosphere seemed bright around the Moon’s rim but lacked the color we saw in 2017. It was a beautiful eclipse, however, and we felt very lucky to have seen it so well.

It’s always struck me as funny that as soon as totality ends, the interest in the rest of the eclipse kind of fades away. But everyone was elated, celebrating a great view, and the party started. We had an airport full of very happy people on a natural high and already talking about other eclipse adventures — Iceland and Spain in 2026, and the most amazing one to come, Egypt in 2027.

I hope that you also experienced a great eclipse; nothing quite equals seeing the worlds align. And remember that the Moon is inching away from us a little bit every year. We have only 600 million more years to catch total eclipses, and then they will be a thing of the past. – David J. Eicher, managing editor of Astronomy

Eclipse perfecto – Mazatlán, Mexico

When I tell people I witnessed 13 total solar eclipses, most of them think there can’t possibly be anything I haven’t seen before. But April 8 proved that there’s always something new under the Sun.

The most impressive of these novel sights were twilight colors that circled the entire horizon. From our vantage point on the center line an hour’s drive east of Mazatlán, Mexico, the Sun stood 69° high during totality — close enough to the zenith that we could see sunlight scattered into the umbral shadow in every direction. The second unusual sight: a brief glimpse with averted vision of the magnitude 0.5 star Achernar hanging low in the south.

Despite the few seconds it took to spot this southern gem, I spent most of the 4 minutes 26 seconds of totality exploring the Sun and its immediate surroundings. The most stunning sight was a large prominence seen near the 4 o’clock position on the Sun’s face. The fiery tongue of hot plasma grew more conspicuous as the Moon slid eastward during totality.

It and several smaller prominences reached into a solar corona that appeared more symmetrical than we expected. The culprit may have been the high, thin clouds above our observing site. Farther away, Venus and Jupiter shone brightly on opposite sides of the eclipsed Sun.

I joined 80 other eclipse chasers on a MelitaTrips tour to Mexico. We all enjoyed seeing sharpened shadows, more intense colors, and projected images of the crescent Sun during the partial phases. And we all felt the 10-degrees-Fahrenheit (6 degrees Celsius) temperature drop from first to third contact. It was a truly memorable experience for the final North American total eclipse until 2044. — Richard Talcott, contributing editor

An eclipse with heritage – Torreón, Mexico

I could read all about what a total solar eclipse entails, and the same goes for a trip to Mexico. But nothing could’ve prepared me for my first experiences of both of these events converging this April on Eclipse Traveler’s program to Mexico City and Torreón.

I was born and raised in America but with Mexican culture, so I didn’t know what to expect from going to Mexico for the first time. As we explored Mexico City’s busy streets, I lost count of the number of vendors gently smiling at me as I passed them, even with no intention of buying anything. Every citizen was walking and moving with determination and warmth; observing this made me proud to be Mexican. A sense of familiarity washed over me as I recognized objects and toys for sale that I knew from my childhood, and when I heard stories I grew up with repeated by our tour guides.

We visited multiple UNESCO World Heritage sites, including Mexico City’s historic center and the colorful district of Xochimilco. We also made a day trip to the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon in the ancient city of Teotihuacán. Archaeologists think the Pyramid of the Sun is aligned to directly face the sunset on the 11th of August and the 29th of April, purposely separated by 260 days, the same length as the Aztec ritual calendar.

There aren’t words strong enough to describe the extraordinary spectacle that is a total solar eclipse — especially your first one. But the best words I can think of are: sensationally phenomenal, spiritual, harmonious, and just absolutely breathtaking! As soon as totality began, the collective shouts of pure excitement and awe made my heart pound and flutter.

The improbability of getting the opportunity to be on this luxurious trip, surrounded by astronomy enthusiasts, and having the clouds clearing up perfectly on time, allowing all of us to gaze upwards (at an altitude of 70°) at the perfect alignment of the Sun-Earth-Moon system, made me want to raise my arms, fall to my knees, and start praying to the eclipse and universe. I completely understand why civilizations felt like they had to make some kind of sacrifice during the eclipse.

Up next are the total solar eclipses in August 2026 and 2027 — they can’t come soon enough! — Daniela Mata, associate editor

To read more about the eclipse in Torreón, click here.

Earning the eclipse – Ingram, Texas

Like many, I suspect, I spent the weekend of April 6–7 reading weather reports, refreshing forecasts, and googling “What can you see if there are clouds during an eclipse?” I didn’t know firsthand what a clouded-out eclipse would be like. But looking at the predictions, I wondered if I’d soon find out.

As part of Astronomy’s partnership with Eclipse Traveler, I joined their U.S. eclipse tour in San Antonio and spoke to the group of nearly 70 eager skywatchers Sunday evening about what to expect and how to safely view the eclipse. Then, we would set out early Monday morning for our viewing site in Ingram, Texas, for 4 minutes 26 seconds of totality.

In my presentation, I covered what to expect, including what to focus on if clouds did mask the view — how the temperature drops and the wind changes, how the sky goes dark. Still, we remained hopeful that we would get to see the corona lighting up the sky.

Monday dawned only partly cloudy — a good sign, I hoped. On the highway outside San Antonio, we passed people setting up telescopes, lawn chairs, blankets, and grills. Hope began to grow.

Our viewing site in Ingram was outside Citywest Church, where we enjoyed an early catered lunch and live music as we set up. Hope soared as the Sun continued making appearances through the clouds. First contact arrived, and we celebrated as the clouds remained mostly at bay.

Unfortunately, as the eclipse progressed, clear patches came with decreasing frequency. It was definitely getting cloudier. This made watching the latter partial phases leading up to totality both more difficult and more rewarding. Every second of waning sunlight was precious.

In the half-hour before totality, the light started to change. Every few minutes, we paused our search to feel what the weather was doing. Admittedly, it was hard to say whether the change was due to the incoming storm front or the approach of totality, but it had to be at least a little of both, right?

The moment totality would begin — 1:32 p.m. CDT — was almost upon us. And then, as we counted down the last minute, a cloud covered the Sun completely. “That’s OK!” I shouted. “The clouds are still moving! We might get a hole!” And with clouds in the sky, I reminded all of us, darkness should fall quickly and completely.

That darkness did fall — profoundly — as the shadow swept in and totality began. With the eclipsed Sun still behind a cloud, we were plunged abruptly into night. On some nearby houses, porch lights popped on.

For at least the first minute of totality, the Sun was completely covered. We got no Baily’s beads and no diamond ring. But we did get a very clear 360° sunset effect and we now felt the temperature plummet.

Then, suddenly, a group down the road from us began cheering. A hole had opened up right over them, revealing the eclipsed Sun, and it was coming to us.

Seconds later, it was our turn to cheer. There it was — the dark Moon, blotting out the Sun like a hole punched in the sky, with a bright, almost uniformly circular corona blazing around it like a sunflower. The corona was dazzlingly bright. It was a breathtaking sight.

The next cloud moved in, again obscuring totality. But now we were energized, excited, and ready for the next break in the cloud cover. At least two more holes crossed overhead, giving us those glimpses of totality that our group had traveled to see. We were ecstatic, hungry for every moment of it.

The final seconds of totality were also lost behind cloud cover, and day dawned over us on fast-forward. Totality was over. But we’d done it. We’d seen it. “We earned it,” Nikolas Xexenis, who’d traveled from Australia to see his first eclipse, said triumphantly.

While our eclipse wasn’t picture perfect, in a way, I think that’s OK. Compared to a clear-sky viewing, we saw a much more marked difference in light at totality’s onset and end, and could take the time to fully explore this strange environment.

We often say that eclipses are all about seeing totality. But a total eclipse is a full sensory experience, not just a visual one. Our group truly experienced totality in every way possible. – Alison Klesman, senior editor

Drama in the heavens – Kerrville, Texas

Having already seen 14 total solar eclipses all over the world, of course my wife, Holley, and I weren’t going to pass up one within driving distance of our house. So we, along with her parents and four friends from Tucson, booked a house in San Antonio that would serve as our base. Early on eclipse day, we headed to our chosen location: Kerrville, Texas.

For several years, the Kerrville Parks and Recreation Department had been planning a huge festival at Louise Hays Park in the city. When I contacted one of the people in charge about our group coming to the event, I was asked to speak to the visitors before the eclipse. In return, we would be provided two choice parking spots and a tent.

Climate statistics had led me to choose a location in Texas. But the week prior to the eclipse proved the old adage, “Climate is what you expect. Weather is what you get.” As April 8 approached, our location had a less than 40-percent chance of being clear. But no nearby (reachable) place seemed much better. So, Kerrville it was. Lots of other people thought so, too. The city’s Convention & Visitors Bureau reported 64,000 visitors throughout the weekend. A preliminary count put more than 20,000 of them in the park on eclipse day.

First contact, the moment when the Moon begins to cover the Sun’s brilliant disk, occurred during my talk. For the next 78 minutes, thick clouds came and went. Every time they parted to reveal a more-obscured crescent Sun, a huge roar would erupt from the crowd. Everyone — including me! — hoped it would clear enough for us to see totality.

The tension was palpable. “Look! There’s the Sun 90 percent covered.” Then clouds. Then it was 94 percent. More clouds. Then 98 percent. As totality approached, darkness covered us like someone pulling a colossal blanket over the park. And then, just seconds before totality, when the Sun’s illuminated portion was the thinnest possible crescent, the sky around our daytime star cleared. “Diamond ring!” I screamed. At this point, both Holley and I were observing through binoculars. We saw Baily’s beads for a few seconds. Then the crimson-red chromosphere appeared. And finally the star of the show — the Sun’s magnificent corona — was there for all to see. This was drama of the highest level.

We all saw the first 45 seconds of totality, and then clouds once again obscured the view. But it was enough, and the many people I talked to afterward were amazed and thankful that we had been able to witness such sublime celestial geometry. — Michael E. Bakich, associate editor