One of 2012’s top meteor events peaks the night of April 21/22. Although the Lyrid shower doesn’t get as much recognition as many summer and autumn showers do, it often puts on nice display. In a good year, observers can expect to see up to 20 “shooting stars” per hour — an average of one every three minutes — at the Lyrids’ peak.

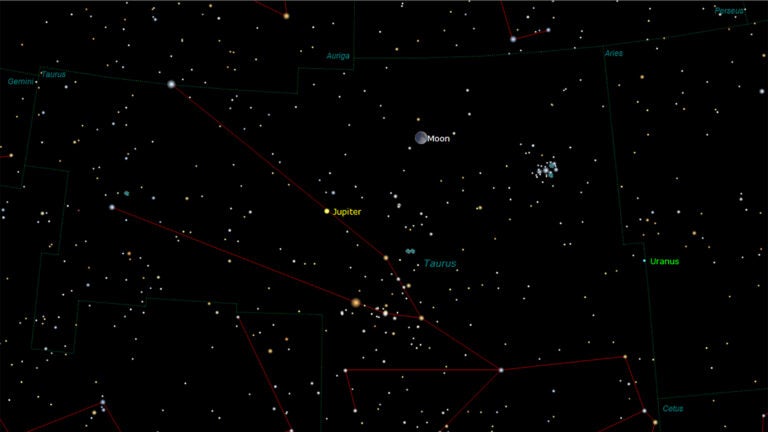

And conditions should be close to perfect this year. New Moon arrives April 21, so our satellite won’t shed any extraneous light into the sky. The Moon’s presence often hinders meteor viewing by drowning out fainter streaks. For the same reason, the best views of the shower will come from observing sites far from the lights of any city.

Senior Editor Michael Bakich of Astronomy magazine loves watching meteor showers. “It has to be one of the easiest, most relaxing forms of entertainment available to backyard skygazers,” he says. “There’s no need for a telescope because optical aid narrows your field of view, and you want to take in as much sky as possible. And best of all, you can observe the spectacle while lying down. Who could ask for more?”

You’ll likely want to watch the sky for an hour or more, so comfort is key. Bring along warm clothes and a blanket. Even if evening temperatures are comfortable, you won’t be active and can get cold in a hurry. Have some hot coffee, tea, or soup to ward off the chill. Plan to recline in a lawn chair or lie down on an air mattress. Sitting up straight or standing for long periods will wear you down.

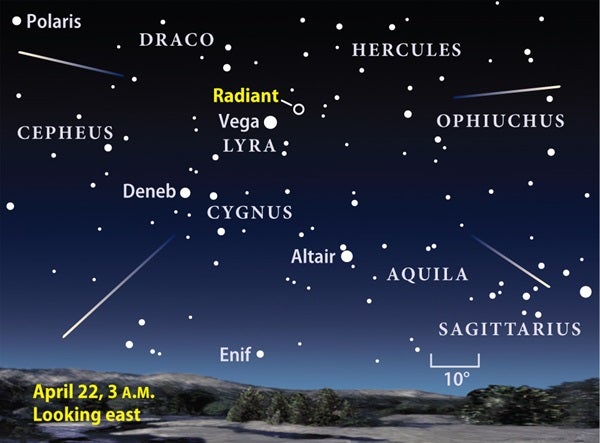

The Lyrids begin as tiny specks of dust that hit Earth’s atmosphere at 109,600 mph (176,400 km/h), vaporizing from friction with the air and leaving behind the streaks of light we call meteors. The meteors appear to emanate from the constellation Lyra the Harp, near the bright star Vega, which rises in late evening and passes nearly overhead shortly before dawn.

For the best views before midnight, look straight overhead. As dawn approaches, look about two-thirds of the way from the horizon toward the zenith in any direction. But don’t get tunnel vision staring at one location. Let your eyes wander, and peripheral vision can pick up meteors you otherwise might not see. Another no-no — don’t stare directly at the radiant. Although all of a shower’s meteors appear to emanate from this spot, any meteor you see there will be just a point of light. All other things being equal, the farther away from the radiant a meteor streaks, the longer its trail will be.

Fast facts:

- The dust particles that create Lyrid meteors were born in an obscure comet known as C/1861 G1 (Thatcher). This object orbits the Sun once every 415 years, the longest period of any meteor-producing comet.

- Although 109,600 mph (176,400 km/h) may seem fast, Lyrid meteors are slower than those in many other annual showers. The Leonids of November top the charts, hitting our atmosphere at 159,000 mph (256,000 km/h).

- Although most shower meteors meet their demise high in Earth’s atmosphere, at altitudes between 50 and 70 miles (85 and 115 kilometers), a few bigger particles survive to within 12 miles (20 km) of the surface. These typically produce “fireballs” that glow as bright as or brighter than Venus.

- Video: Easy-to-find objects in the 2012 spring sky, with Richard Talcott, senior editor

- Video: How to observe meteor showers, with Michael E. Bakich, senior editor

- StarDome: Locate Saturn in your night sky with our interactive star chart.

- The Sky this Week: Get your Lyrid meteor shower info from a daily digest of celestial events coming soon to a sky near you.

- Sign up for our free weekly e-mail newsletter.