Astro Influences: Michelle Thaller

Michelle Thaller is the manager of the Spitzer Space Telescope Education and Public Outreach Program.

How did you get interested in astronomy?

Scientists are sort of loners, aren’t they? They’re motivated by a pure sense of inquiry and the drive to discover something new about the universe. They’re well-organized, linear thinkers who feel at home in the rational, logical world of science. That’s always the sort of person I’ve wanted to be, but it bears little resemblance to who I actually am.

I became an astronomer partly because of the social approval. Whenever I showed interest in astronomy as a child, I was showered with attention. My dad, a geography professor at Carroll College in Waukesha, Wisconsin, was proud to have an offspring (a girl even!) who understood science. Dad was always a bit suspicious of women and their intractable emotional ways. With science, I could show my father how much I loved him. And by the 1970s, teachers knew it was important to encourage a girl to pursue science. When I spoke about wanting to be an astronaut or a scientist, I got attention and approval in big, warm helpings.

Now, there was absolutely nothing wrong with any of this. Young women should be encouraged to go into science, by all means! It is, however, interesting to me that in a world where we are seeking equality between the sexes, I got far more praise for doing nontraditional things for a girl than if I had been involved in choir or art club. Do boys get praise heaped on them for excelling in home economics or language arts — some of the more traditionally female topics? Somehow, I think not. That’s something to consider as we try for true equality. For me, being more like a boy was, by definition, a good thing.

But of course, there had to be an innate interest in astronomy. At an early age, I had an intense curiosity about how the physical world works. I realized if you keep asking “Why?” to just about anything, you get to physics — quantum mechanics, to be specific. I’m more of a physicist than anything.

I’m definitely more of a physicist than anything. I never had a telescope, nor wanted one much, and to this day I doubt I could set up an equatorial mount. That’s an embarrassing part of being a professional astronomer — amateur astronomers are the real astronomers. We’re just physicists pretending to be astronomers. I go to the Keck Observatory and stay at the comfortable sea-level headquarters while some poor observing assistant at 14,000 feet elevation types in my coordinates. Or more usually I submit a proposal for time on the Hubble Space Telescope and get my data neatly packaged and cleaned about 6 months later. I can’t sight any deep-sky object to save my life, and, yes, that does bring me some shame.

But back to the physics. Physics is basic to being comfortable with the reality in which we find ourselves. Can you imagine telling a child that those little white lights in the Wisconsin sky are actually vast, burning hydrogen bombs a million miles across and just too massive to explode? We’re seeing them from trillions of miles away — can you imagine how hot they must be? Because I love all things dramatic — from dressing up in science-fiction costume to performing at Renaissance faires — these spectacular processes found in our universe grabbed my attention, and I was hooked for life.

I am still sustained by the overwhelming awe and joy I get just thinking about these things. In my day job, for which I am well-paid from public funds, I get to think about black holes, gamma-ray bursts, life on Mars, and microwave background radiation! Yes, about 80 percent of my time is spent searching for funds, proposing for telescope time, writing reports, and dealing with campus, state, and national politics. But it is actually my job — not some time on the Internet I’m guiltily sneaking in between doing my real work assignments — to think about the universe and how best to communicate its wonders. Amazing! I should pay NASA to do that part of the job, not the other way around.

And maybe that feeling alone should be enough to convince me that I am, in fact, a real scientist and not some kind of imposter. Maybe I am more creative than analytical, going more on instinct than logic. Maybe I’m not a terribly organized thinker (or desk-keeper for that matter). The subject of astronomy is bigger than one version of what an astronomer should be like. It takes all kinds.

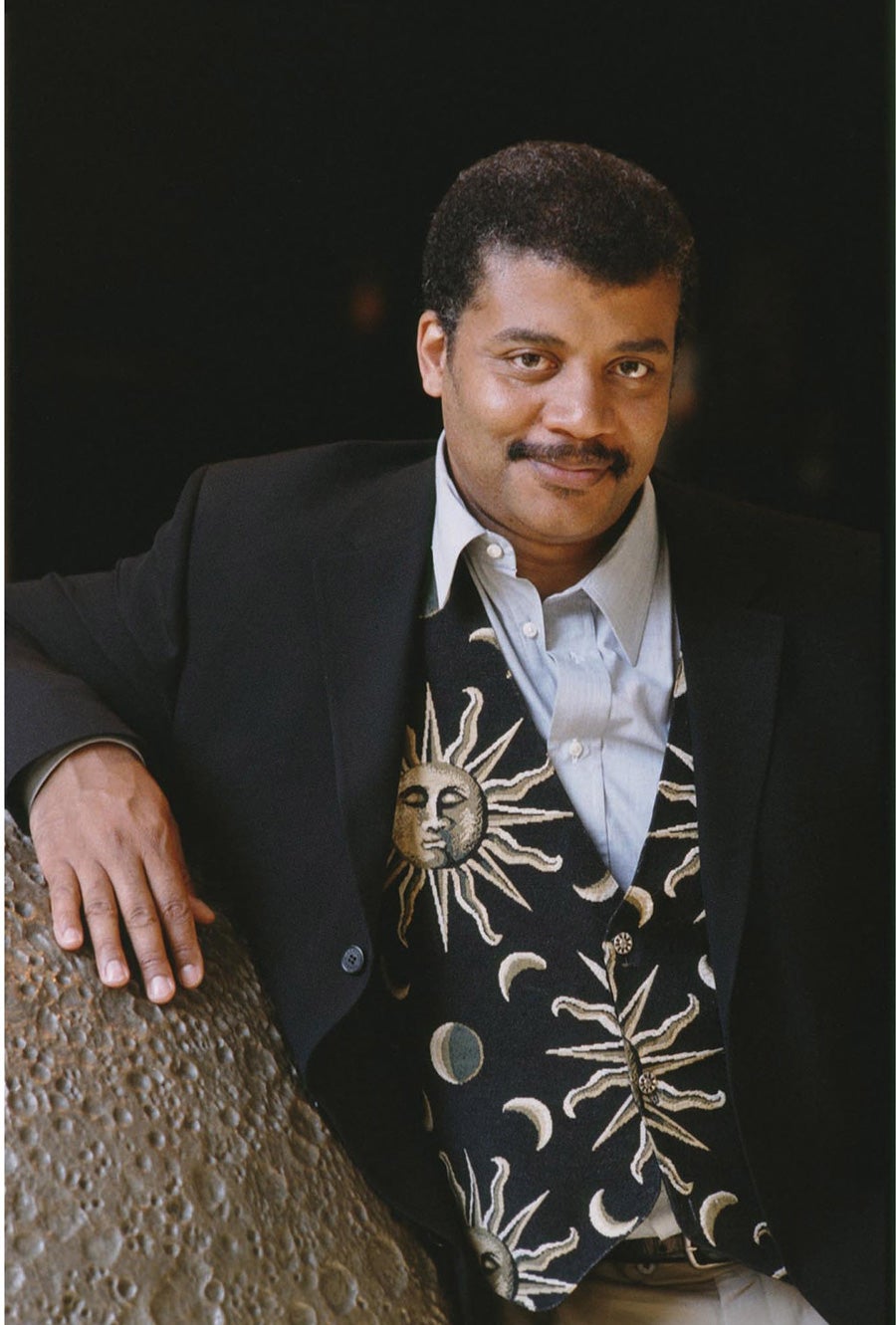

Getting to Know Neil deGrasse Tyson

Neil deGrasse Tyson is the director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York and the author of The Pluto Files: The Rise and Fall of America’s Favorite Planet (W. W. Norton, 2009)

What is the coolest thing you’ve gotten to do in your career so far?

One really cool thing was playing a cameo in Stargate Atlantis. But I wish I were a better actor because, embarrassingly enough, I was playing myself. Presumably, whatever I did should have been me, but when I saw it at home, I thought I sucked. Still, I enjoyed the experience, and I enjoyed hanging out with the actors and watching the making of a television show.

Another very cool thing was serving on a presidential commission to study the health of the American aerospace industry, which involved exploring the economic climate of aerospace around the world. As a commissioner, I traveled around the world to major aerospace centers. That journey was unforgettable for me.

How do you think we can get more people excited about astronomy?

A lot of people already are excited about astronomy. Compared with other sciences — at least those that don’t affect our daily lives, such as health — astronomy does very well. Look at the popular press. Astronomy often makes headlines. Take Mars or the Big Bang. Just look at the reaction to Pluto.

I can gauge excitement just by when my phone rings because a producer at a news station calls to get a sound bite on some recent headline. So in that respect, I think we’re doing quite well.

We also have a unique opportunity with the International Year of Astronomy, especially if we can pull it off — getting all 6.75 billion people on Earth to look through a telescope. A view of the universe has a profound impact. There’s no greater instrument to look back on where you came from.

That’s what happened during the Apollo era. Apollo 8 was the first spacecraft to leave low Earth orbit and get a good enough distance from Earth to look back and take a picture. It’s that image that’s traceable to the birth of the modern conservationism movement because we saw Earth without national boundaries.

What do you do in your spare time?

I like wining and dining with my wife, and I like playing with my kids and watching them grow intellectually. I also enjoy going to Broadway shows.

I like reading old science books that go back centuries. They sensitize me to how people used to think about the natural world. And I like to probe how ideas have changed over time from the original books, sometimes requiring translation from Latin or other languages.

I have fountain pens and quill pens and an ink well, and I like to write by candlelight with those pens on parchment, for no reason. Or I like to write at night on the beach with the sky above, the ocean in front of me, and my writing in my lap. I long for the day when the writing on the page was more than just the information contained in the word itself, when you could convey the feeling, flair, and meaning of the word simply by how you wrote it.