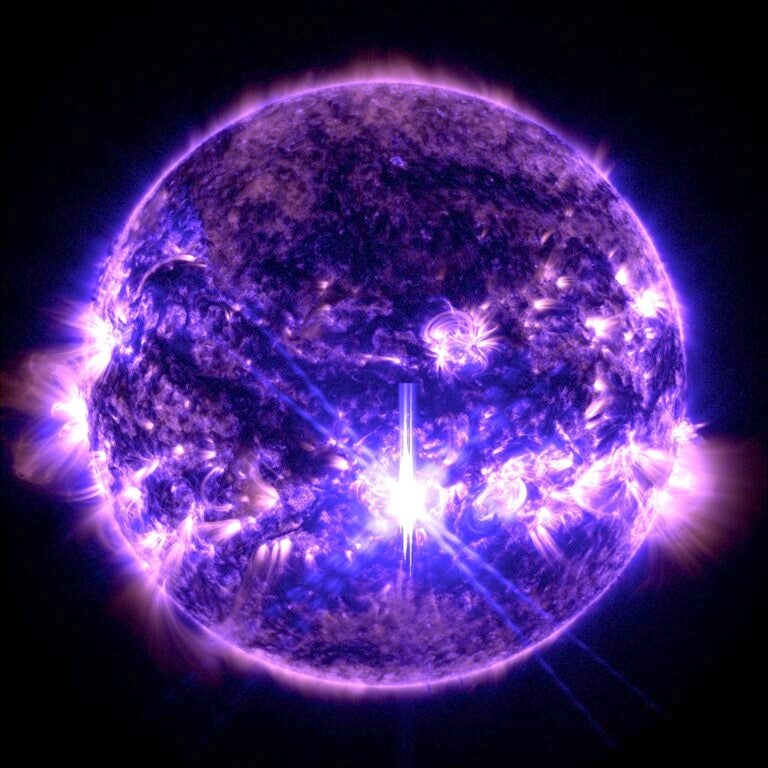

Hahn and Savin analyzed data from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrometer aboard the Japanese satellite Hinode. They used observations of a polar coronal hole, a region of the Sun where the magnetic fields lines stretch from the solar surface far into interplanetary space.

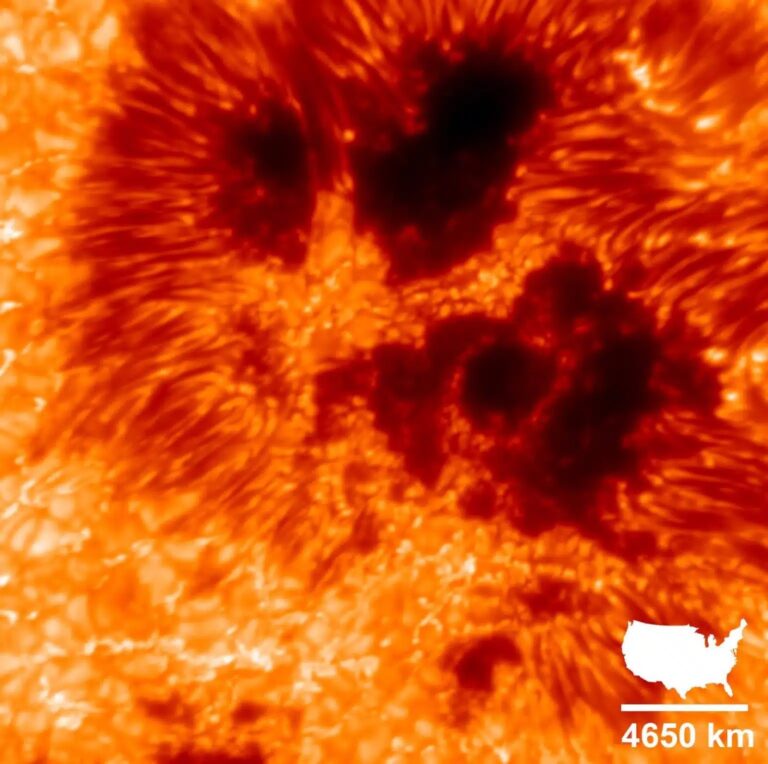

To understand the coronal heating problem, imagine a flame coming out of an ice cube. A similar effect occurs on the surface of the Sun. Nuclear fusion in the center of the Sun heats the solar core to 15 million degrees. Moving away from this furnace, by the time one arrives at the surface of the Sun, the gas has cooled to a relatively refreshing 10,800° Fahrenheit (6,000° Celsius). But the temperature of the gas in the corona, above the solar surface, soars back up to over 1.8 million degrees F (1 million degrees C). What causes this unexpected temperature increase has puzzled scientists since 1939.

Two dominant theories exist to explain this mystery. One attributes the heating to the loops of the magnetic field, which stretch across the solar surface and can snap and release energy. Another ascribes the heating to waves emanating from below the solar surface, which carry magnetic energy and deposit it in the corona. Observations show both of these processes continually occur on the Sun. Until now, scientists have been unable to determine if either one of these mechanisms releases sufficient energy to heat the corona to such high temperatures.

Hahn and Savin’s recent observations show that magnetic waves are the answer. The advance opens up a realm of further questions, chief among them is what causes the waves to damp. Hahn and Savin are planning new observations to try to address this issue.