Key Takeaways:

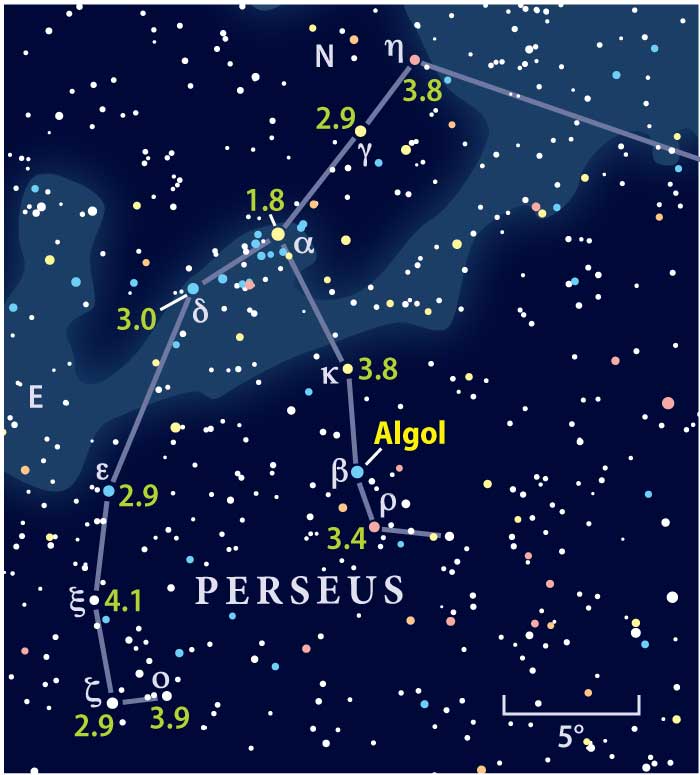

Why should emission nebula IC 1396 attract a crowd of more than two dozen to an 18-inch Dobsonian at the Connecticut Star Party (CSP)? One might think the Index Catalogue consisted of B-grade objects too faint or minor to make it into John Dreyer’s New General Catalogue, but this sight proves otherwise. It happens to be the home of my favorite multiple stars — Struve 2816, a tight triple sun, and Struve 2819, a double system.

These beauties lie in Cepheus the King, making them viable targets every night throughout most of North America. At the star party, everyone who looked through the mighty scope beheld a panorama of majestic suns ambling around the “best actors” that dominate the field.

More recently, I realized how the presence of the surrounding cluster enriches the view of these beautiful stars, making the pair an ideal star party target. And despite the clouds occasionally blocking the sky, the 20th annual CSP was one of the best yet. The sky that Saturday night in early September was clear enough to allow views of many bright objects, from the International Space Station to Jupiter to the lovely stars of IC 1396.

Managed effectively and imaginatively over the past few years by amateur astronomer Greg Barker of the Astronomical Society of New Haven, the CSP provided its participants a wonderful chance to reconnect with the night sky. Across the wide observing field stood a jungle of telescopes big and small.

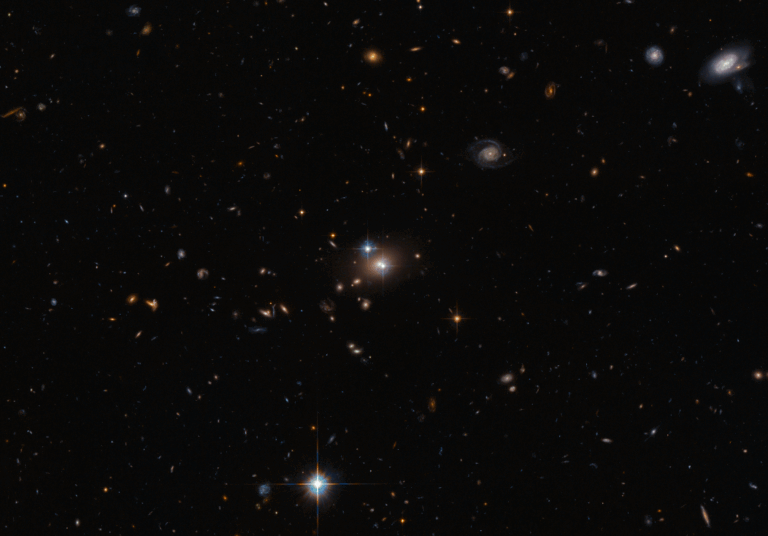

During our daylong talk, Carolyn Shoemaker and I gave presentations and led discussions. Carolyn focused on the events that have occurred on Jupiter since 1994, when 21 fragments of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 (S-L 9) — each racing at 134,000 mph (216,000 km/h) — slammed into Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. They left dense clouds of soot-like particles that showed up more clearly than any other feature on the planet in the past four centuries, according to planetary astronomer Clark Chapman. Carolyn also focused particularly on the three recent impacts and the increasing data astronomers are collecting on potentially threatening asteroids and comets.

For my turn, I gently invited the audience to follow me back in time to a moonlit evening in early 1971, just after the Apollo 14 mission. There, while carrying a portable cassette player, I listened to the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata No. 14 in C-sharp minor, commonly known as his Moonlight Sonata. Accompanied by photographs and paintings of the Moon, the crowd and I reminisced about what observing used to be like. Eventually, I led the group back to the recent past, where comets, collisions, and Shakespeare have taken up my waking hours.

After 16 years, humanity’s first witness of a cosmic impact in 1994 still presents unanswered questions. How big was the progenitor comet? How often does Jupiter experience such impacts? As to the latter, recent evidence suggests that while events like S-L 9 are still very rare, perhaps occurring once every two millennia, smaller impacts from single objects seem to hit the planet far more often, maybe as frequently as once every few weeks.

While all this violence transpires on Jupiter, Earth proves a far less tempting target. On the second night of the star party, the sight of a few meteors scratching the Connecticut sky punctuated our viewing as they sped toward their fiery destruction in Earth’s atmosphere. I saw two, and one of the youngest people in the crowd spied two more.

We often gather at star parties simply to test the latest observing technology, hoping to use it under a clear sky. But, whether it’s lovely multiple stars or destructive planetary impacts, the night sky reminds us of the real reason we come — to recharge our observing batteries and to remind ourselves of the beauty and mystery that attracted us to this pastime in the first place.