Most travelers who ventured to see the April 20, 2023, hybrid solar eclipse headed for Western Australia, where a narrow spit of land jutting into the Indian Ocean was grazed by a minute of totality.

Fewer ventured to East Timor, where the Sun’s shadow passed across the country from south to north. But I leapt at the chance: It would be my first time standing in the Moon’s full shadow. And visiting one of the world’s youngest countries — plus spending the rest of the week in Indonesia — was too intriguing a travel opportunity to pass up.

It took 24 hours in the air across four flights to get from Milwaukee to Jakarta, where I rendezvoused with the expedition organized by Eclipse Traveler, Astronomy’s official travel partner, led by Mesut Pehlivan and planned by him and the company’s founder, Cengiz Aras. The morning before the eclipse, we flew into East Timor’s capital city of Dili, where we were welcomed by our local guides and a group of college-age dancers and drummers in traditional Timorese dress. (Music students? I asked. No, tourism majors, they told me.)

Our head guide in East Timor was Aday Lebre, an energetic man with an easy smile and unbridled enthusiasm. It was immediately clear that he and his crew would be invaluable and knowledgeable ambassadors. As we drove along Dili’s waterfront, Aday delivered a (very) brief history of the nation: colonized by the Portuguese, occupied by Japan in World War II, and then invaded by the Indonesian dictator Suharto in 1975. The invasion marked the start of a brutal, genocidal occupation. After a long resistance, the nation won its independence in 2002. “Freedom for us is like a bounty from God,” said Aday — hence the name of his company, Bounty Timor Tours.

In fact, national pride was evident all around us: By chance, we had arrived on the first day of the monthlong campaign season for the nation’s parliamentary election. As we motored out of Dili into the surrounding foothills, the scenery included markets filled with papayas and bananas, street dogs, tied-up goats, free-roaming cows — and convoys of campaigning candidates, their trucks packed with supporters and flying the flag of their political party.

The road less traveled

That most travelers chose to view this eclipse from Down Under was not just due to a lack of familiarity with East Timor. While Australia’s Cape Range is known for its clear skies, data suggested that our chances of cloud-free viewing in East Timor were perhaps 50-50. To maximize our odds, Eclipse Traveler’s planners had chosen the southern coast, which appeared to receive less cloud cover. The expeditions that shared our flight into Dili were headed for the beachside town of Com on East Timor’s northern coast, a spectacular drive along seaside cliffs that reminded me of the Pacific Coast Highway. We followed this route for a couple of hours too, in our convoy of three Toyota 4WDs and a pickup truck. We drove past beaches, mangrove forests, and fishing villages with outrigger canoes at anchor. Sprinkles of afternoon rain cast rainbows over the mountains as sunshine burst off the sea. Then, when our convoy reached the city of Baucau and the Sun was diving for the horizon, we turned south, into the mountainous interior of the country and a steady drizzle.

Here, my jet-lagged body took a beating as we traversed a washed-out gravel road. Any hopes of sleep were knocked out of my head as the bumps slammed it against the window. Outside, the darkness was interrupted occasionally by boulders, mud piles, and the spray of water as we splashed through flooded sections of road. Our drivers navigated around sinkholes that revealed half-buried pipes — presumably meant to drain some of the water we were splashing through — and crept across narrow bridges with 30-foot (9 meters) drop-offs on either side.

At one point, our convoy came to a halt when the headlights on the truck behind us went out. With no fix coming, Aday spent the rest of the drive with his legs dangling out the back of our vehicle, pointing a flashlight past his feet to light the road for the truck behind us. It was around 11 P.M. when we arrived at our guesthouse in the town of Viqueque (population: roughly 7,000). After a quick bucket shower (the running water was off for the night), I was fast asleep.

The eclipse’s first contact would occur at 11:44 A.M. local time, with totality beginning at our site one second before 1:19 P.M. It would last for 75 seconds, just one second shy of the eclipse’s maximum duration. We set out around 8:30 A.M. for the 45-minute drive to the beach at the town of Beaco. Now we could see the landscape we were driving through — muddy cliffs, swift rivers, and villages where the entire population would smile and wave and the kids would shout “Hello!” as we rolled through.

The locals would have their own unique response to this eclipse, Aday told us. “Many Timorese believe that if dark is coming, then it’s the end of the world,” he said. “You may hear some noise, like beating on pots and pans. They want to say, ‘God, we’re still alive!’”

When we arrived at Beaco, the skies were clear, waves were lapping at the shores, and hundreds of people — nearly all locals — had gathered. Government officials were there, too, working the crowd, including Minister of Tourism, Trade and Industry José Lucas do Carmo da Silva (a marine biologist by training).

Underneath large tents next to the ruins of a colonial-era Portuguese customs office, the government had catered an enormous spread of Timorese food for everyone on the beach. It was an introduction to eclipse chasing that will probably spoil me forever — munching on a plate of fresh seafood and meat skewers and sipping water from a coconut.

Collective thrill

And then the show began.

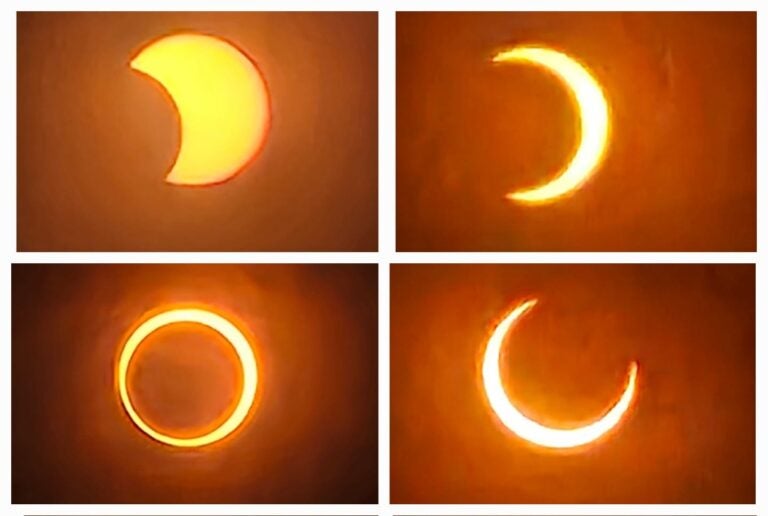

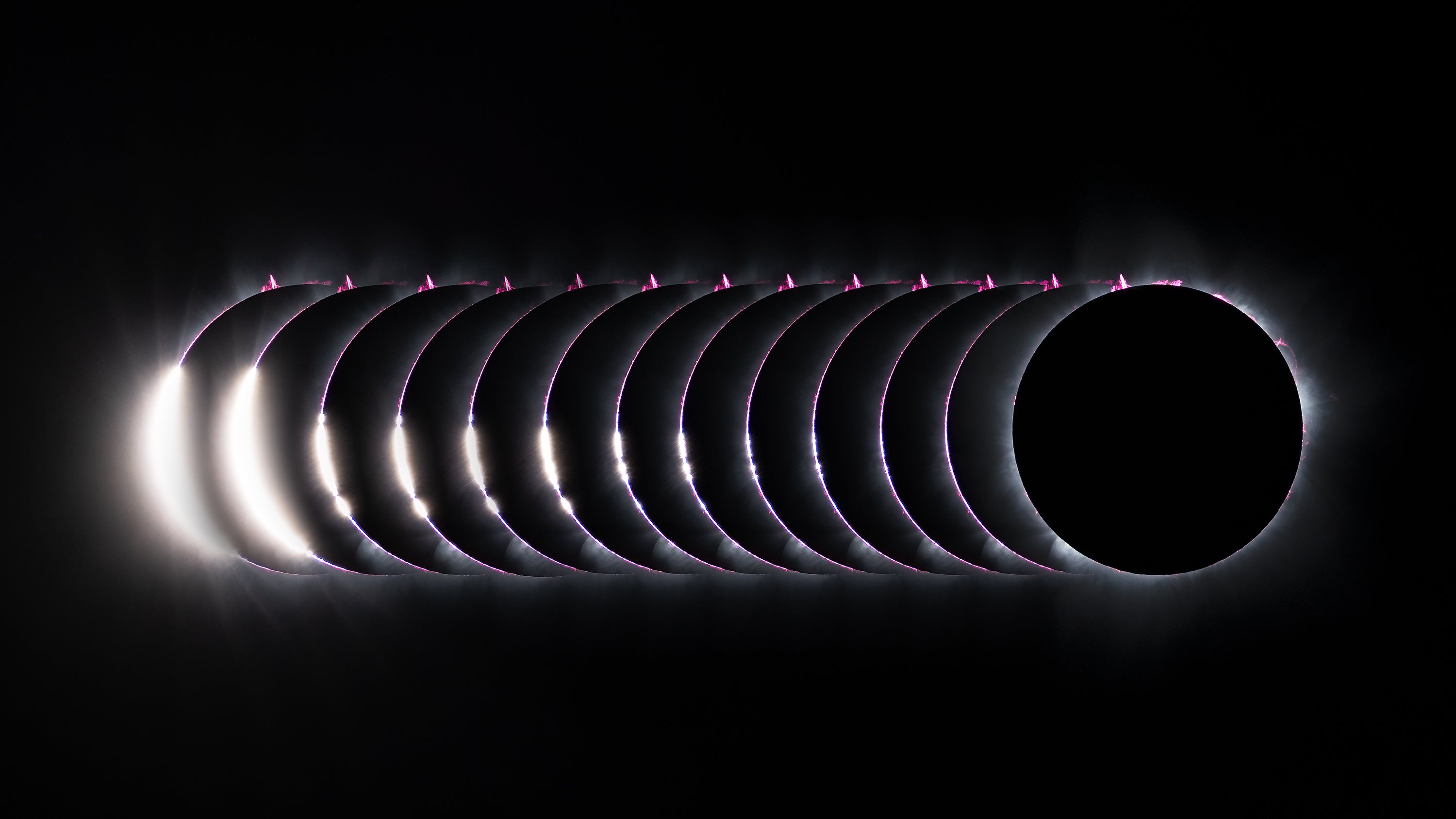

It was a warm day and half an hour before totality, you could feel the drop in insolation on your skin. Shadows took on extra sharpness and intensity, and 10 minutes out, the crowd began to buzz as the world grew visibly dimmer. With two minutes to go, we could see the faint cone of shadow on the horizon, approaching over the sea from the southeast.

Sixty seconds out, a swell of cheers and gasps arose from the crowd as the remaining sliver of Sun began disappearing from its tips. Just as the Sun was about to wink out of view, a brilliant string of Baily’s beads appeared.

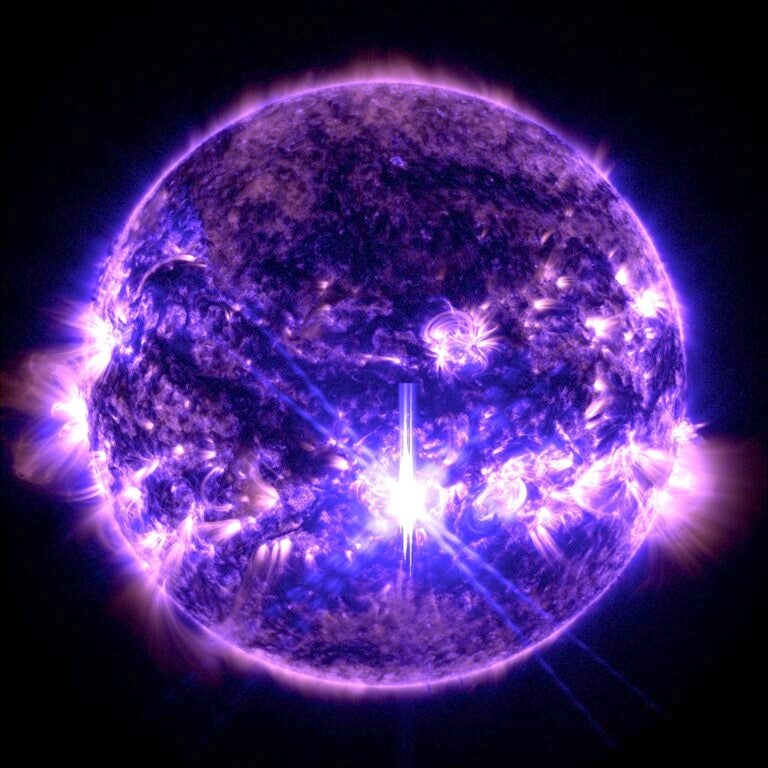

And then, totality — and goosebumps. Our view of the corona materialized almost immediately, though it took me a few seconds to process what I was seeing: The active Sun looked almost like a cartoon drawing of a star, bedecked with seven or eight points in the form of coronal streamers. I could see multiple prominences with the naked eye, including a particularly impressive one on the Sun’s lower left limb. Jupiter had also appeared in the darkness, roughly 6° away.

For the next minute we buzzed in a state of collective ecstasy, with a constant roar of shouting and cheering. In the darkness, another constellation of lights emerged around me — the screens of smartphones aimed at the sky. Out at sea was the faint glow of twilight.

Upon third contact, when totality came to an end, a brilliant diamond ring appeared. As the Sun returned, the crowd roared even louder than it had during totality. I realized that I hadn’t heard any beating on pots and pans — just expressions of joy, awe, and the feeling of sharing in witnessing something so much greater than any of us.

In the strengthening light, I saw Aday and his guides jumping around and spraying champagne across the beach like race-car drivers celebrating a victory. No wonder: For Aday and our partners at Eclipse Traveler, the moment was the culmination of years of planning. Those of us on the beach were lucky.

Unfortunately, not everyone who had the chance to experience the eclipse in East Timor did. We later heard that the scene was very different in Dili, just outside the path of totality. There, the eclipse was just shy of total, at 98 percent — far from the full experience, of course, but still one to savor. But as the Moon covered the Sun and the midday twilight fell, the streets emptied and people stayed inside.

Numerous people told me that misinformation on social media had convinced many that the eclipse was a dangerous event and to avoid exposure at all costs. Of course, even a 98-percent-eclipsed Sun requires proper eye protection or projection techniques to view safely, so perhaps genuine warnings had been exaggerated. But the result was that many people were robbed of the chance to see what could have been the celestial experience of their lifetime. It was a reminder of the importance of accurate science communication, and that not everyone has access to it.

More than an eclipse trip

The two days after the eclipse were full of excursions — including to the statue of Christ overlooking Dili’s seaside, a colonial-era Portuguese fort and prison, a plantation growing coffee (one of East Timor’s few exports besides offshore oil), and a memorial to the Timorese criados — children who volunteered as guides and served as companions and protectors alongside the Australian special forces who waged a yearlong guerrilla campaign against the Japanese in World War II.

Perhaps the most moving visit was to the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili, where Indonesian forces massacred over 250 unarmed pro-independence protestors on Nov. 12, 1991. The event shocked the world and marked a turning point in the nation’s struggle for independence. It was clear from Aday and our guides how proud East Timorese are to have a political status that reflects who they are as a people, and to have obtained — at high cost — their right to self-determination.

The trip was far from over. Still ahead were five days of exploring Indonesia. We flew to Bali, where we rode motorbikes to a Hindu temple on the rim of a caldera, across from the stratovolcano Mount Batur. We hopped over to Yogyakarta, where we visited two UNESCO World Heritage Sites in one day: Borobudur, the largest Buddhist temple in the world, and Prambanan, Indonesia’s largest Hindu temple. And back in Jakarta, we visited the Dutch colonial-era old town, where century-old wooden trading ships still make port.

For many of us fortunate enough to travel around the world to chase totality, the experience can be fleeting. Parachute into a remote locale chosen by the gears of celestial motion, stay a week or two, and then leave. But the impression it leaves can last a lifetime.

Aday had hoped the eclipse would also have a lasting impact for East Timor, boosting the country’s nascent tourism sector. Toward the end of our time there, I asked him if he thought that boost would materialize. He doubted it, he said. When he had brought it up with the tourism ministry, they had dismissed him, he said, appearing to have been unaware of the eclipse and the attention it could attract. By the time they heard about it from other sources, it was too late to build up a larger effort.

I was sorry to hear it. I could only be grateful to Eclipse Traveler and Aday’s efforts. For us, the trip had been a chance not just to see an eclipse, but to learn about the political history of the region — the story of human exploration, the legacy of colonialism, and the price of freedom and self-determination.

The only thing we hadn’t had much of was clear dark skies. Between light pollution and the humid tropical nights, I can recall only one occasion where we had a clear view of the southern sky. It was on our drive back to Dili, as we careened down the winding roads carved into the canyons and cliffsides on the coast. I stuck my head out the window, inhaling the smell of the sea. I could see the Milky Way and Orion high overhead. The Big Dipper hung low in the sky above the ocean, upside down, pointing to Polaris, somewhere over the horizon.