Nightfall comes early in November, aided by the Sun’s southward plunge through Earth’s sky and the return of standard time to most of the United States and Canada. For skywatchers, the early arrival of darkness brings nice views of nearly all of the solar system’s major planets. Only Jupiter, which dazzles in the predawn sky, misses out on the action.

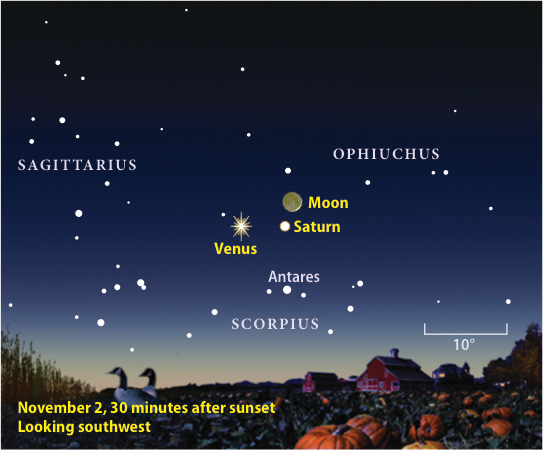

On November’s first evening, a slender crescent Moon paints a pretty scene with Venus and Saturn. Look for Venus 10° above the southwestern horizon 45 minutes after sunset. Gleaming at magnitude –4.0, the inner planet stands out despite its low altitude and the twilight glow. Next, look for the two-day-old Moon 15° (two binocular fields) to the right of Venus. As the sky darkens, Saturn pops into view 5° to Venus’ right. Shining at magnitude 0.5, the ringed planet could be a challenge for naked-eye observers under less-than-ideal conditions. Use binoculars if you want to see the 1st-magnitude star Antares 7° below Saturn.

By the next night, the waxing crescent Moon has moved to a position 4° above Saturn. With each passing evening, the Moon climbs higher while Saturn dips lower. The planet disappears into bright twilight by late November.

Like the Moon, Venus ascends into a darker sky as the month progresses, though at a far slower pace. Its path takes it in front of the magnificent backdrop of Sagittarius during mid-November. Although most of this constellation’s deep-sky objects won’t show up in twilight, observers and imagers will experience more dark skies as the planet’s angular distance from the Sun increases.

Venus lies within 2° of the Lagoon Nebula (M8) from November 11–13, passing just 1.2° south of the stellar nursery on the 12th. The Trifid Nebula (M20) stands 1.4° north-northwest of the Lagoon with the open star cluster M21 just 0.7° northeast of the Trifid. Venus appears as a dramatic if temporary jewel among these regular deep-sky gems.

The planet spends November 16 and 17 within 1° of Lambda (λ) Sagittarii, the 3rd-magnitude star at the top of the Archer’s Teapot asterism. On the 16th, Venus passes 0.7° south of the 7th-magnitude globular star cluster M28. Two nights later, it slides 1.6° south of the 5th-magnitude globular M22. This is the last of the planet’s Messier encounters this month. By November’s close, the inner world pulls within 1° of the magnitude 4.6 double star 52 Sgr in eastern Sagittarius.

A telescope reveals modest changes in Venus’ appearance this month. On the 1st, the Sun illuminates 78 percent of the planet’s 14″-diameter disk. By month’s end, the phase wanes to 69 percent lit while the diameter swells to 17″.

Venus isn’t the only planet to visit 52 Sgr in November. Mars begins the month 3° northeast of this double. The Red Planet shines at magnitude 0.4, some 50 times brighter than the distant pair. The waxing crescent Moon appears near Mars on both the 5th and 6th.

Mars crosses from Sagittarius into Capricornus on November 8 and makes it across much of this constellation by month’s end. On the 30th, it appears midway between the 4th-magnitude stars Theta (θ) and Iota (ι) Capricorni. The planet’s rapid eastward motion relative to the background stars means that it sets less than five minutes earlier at the end of November than it did at the start. Still, your best views will come soon after twilight ends.

Unfortunately, the appearance of Mars through a telescope pales in comparison to what it delivered this spring and summer. Its disk now spans 7″ and likely will look like a featureless orange globe through small scopes. With an 8-inch or larger instrument and steady seeing conditions, you might detect a few subtle dark markings. Winter begins in Mars’ northern hemisphere at the solstice on November 28.

Neptune normally reveals itself by moving relative to the background stars, but this month it barely crawls. (The planet reaches its stationary point on November 20.) To confirm a sighting, aim a telescope at your quarry. Only Neptune will show a distinctive blue-gray color. And under high magnification and good seeing conditions, you should be able to discern the ice giant’s 2.3″-diameter disk.

Uranus climbs highest in the south in midevening, when it stands nearly two-thirds of the way to the zenith. It resides among the background stars of Pisces, a dim zodiacal constellation that offers few easy reference stars. The best guide is magnitude 5.2 Zeta (ζ) Piscium. On November 1, the planet appears 1.7° east of Zeta; the gap closes to 0.9° by the 30th.

Uranus glows at magnitude 5.7, bright enough to see with the naked eye under a dark sky and an easy target through binoculars. Don’t confuse it with 88 Psc, a magnitude 6.0 star that lies 0.6° south-southeast of Zeta. A telescope removes all doubt by showing the planet’s distinctive blue-green color and 3.7″-diameter disk.

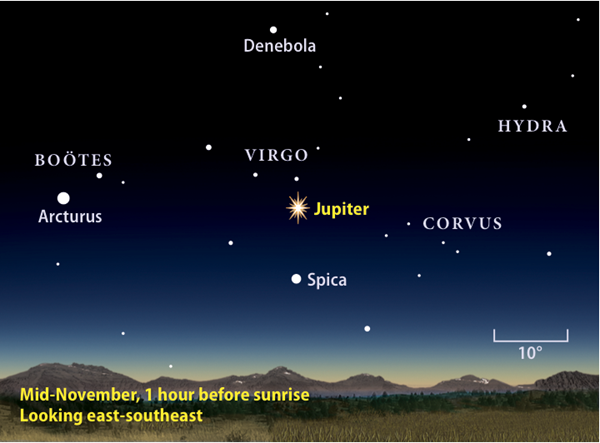

As Uranus dips low in the west during the wee hours, Jupiter pokes above the eastern horizon. The giant planet shines at magnitude –1.7 and dominates the morning sky from its perch in central Virgo. On November 1, it stands 2° south of 3rd-magnitude Gamma (γ) Virginis. Jupiter’s steady eastward motion during the month carries it within 8° of 1st-magnitude Spica, Virgo’s luminary, by the 30th. The star appears directly below the planet as the two climb higher in the southeast before dawn.

Calm morning air can provide excellent seeing conditions for viewing Jupiter’s atmospheric features through a telescope. Two dark equatorial belts straddle the gas giant’s equator, which spans 32″ in mid-November. Fine details often pop into view along the edges of these belts. Keep an eye out for spots, festoons, rifts, and the Great Red Spot.

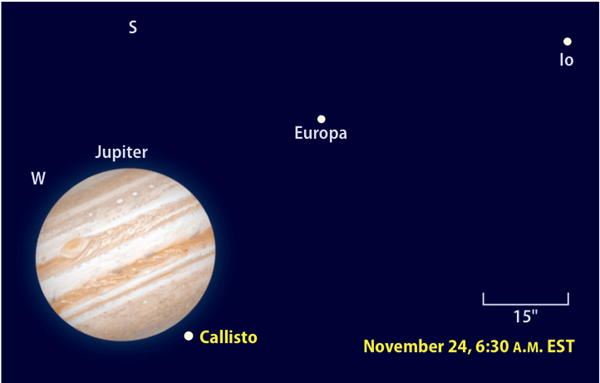

Any telescope also reveals Jupiter’s four bright moons. When one of the three inner satellites — Io, Europa, or Ganymede — crosses in front of Jupiter, it casts a distinct shadow on the cloud tops. November’s first good viewing opportunity occurs on the 5th, when Io’s shadow arrives on the jovian disk at 6:50 a.m. CDT (the Sun already has risen for East Coast observers). The disk of Io itself follows 38 minutes later.

If you live in eastern North America, watch Jupiter as it rises on November 8. The shadow of the planet’s largest moon, Ganymede, then appears on the giant world’s north polar region. The moon starts to cross the planet’s disk at 5:03 a.m. EST. Similar performances occur with Io on November 21 and with Europa on the 22nd.

But perhaps November’s most noteworthy satellite show happens the morning of November 24. Callisto, the outermost Galilean satellite, then passes due north of Jupiter. For North American observers, this is the first time in 3.5 years that Callisto hasn’t crossed in front of the planet. Such a near miss can happen only during the relatively brief window when the common orbital plane of the moons tilts near its maximum to our line of sight.

Earth’s Moon reaches a milestone of its own this month. Full Moon arrives on November 14 just 2.5 hours after its closest approach to Earth since 1948. That makes this Full Moon abnormally large — 33.5′ in apparent diameter — some 7 percent larger than normal. Still, this difference is hardly noticeable to the naked eye. Any Full Moon appears bigger when it’s near the horizon and your mind compares it with familiar objects nearby, even though it comes closer when overhead. For North American observers, this month’s “Super Moon” will look largest as it sets the morning of the 14th.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS | ||

| Evening Sky | Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (southeast) | Uranus (southwest) | Jupiter (southeast) |

| Venus (southwest) | Neptune (west) | |

| Mars (south) | ||

| Saturn (southwest) | ||

| Uranus (east) | ||

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

The peak at the end of the rainbow

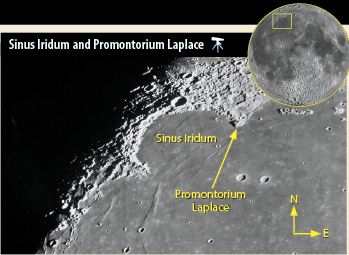

The Moon’s northwestern quadrant includes many bright craters and a vast sea of frozen lava, but one of its most prominent features is a small bay surrounded by a semicircular arc of mountains. Sinus Iridum (Bay of Rainbows) and Montes Jura (Jura Mountains) create a striking scene when the Sun rises over the region the evening of November 9.

The leading peak, Promontorium (Cape) Laplace, casts a long shadow across the bay’s undulating lavas. Watch it shorten over a few hours as the Sun climbs higher and starts to drape its light down the mountain’s western flank.

The Jura’s highest peaks, which lie on the terminator’s dark side on the 9th, flicker in and out of view, changing color the same way Sirius does when it twinkles. Perhaps this is why Italian astronomer Giovanni Riccioli named this the Bay of Rainbows. Several long wrinkle ridges stretch south of the bay. Although clearly defined by their shadows on the 9th, these ridges disappear day by day under the higher Sun.

Three years ago, China landed its Chang’e 3 spacecraft and Yutu (Jade Rabbit) rover just outside Sinus Iridum. Scientists deduced that the surface there is volcanic basalt and a full billion years younger than the 4 billion-year-old samples returned by Apollo astronauts.

Luna spoils Leo the Lion’s show

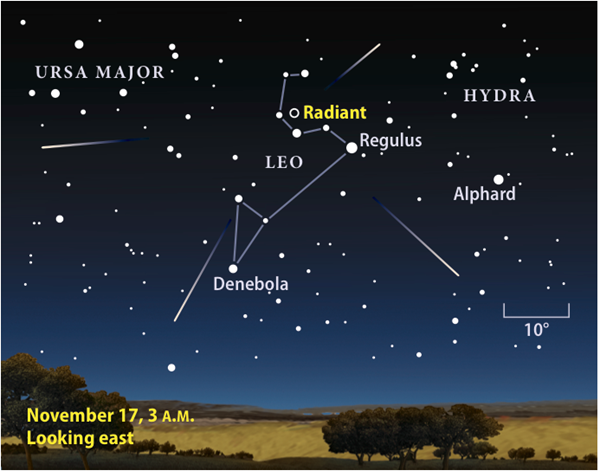

Although autumn boasts the most major meteor showers, the Moon puts a damper on this year’s displays. Like October’s Orionids, a waning gibbous Moon shares the sky with this month’s Leonid meteor shower. The Leonids peak before dawn on November 17, when a nearly 90-percent-lit Moon stands 55° away from the shower’s radiant.

The shower remains active from November 6–30, however, so you should see a few stragglers in the days before the November 14 Full Moon and again in the month’s final week. To tell a Leonid from a random meteor, trace its path backward. A shower meteor will appear to originate from the constellation Leo the Lion.

Famine before the feast

Many comet observers have been nibbling on scraps for an unusually long period. Although we got a lucky break in March when Comet 252P/LINEAR had an unexpected outburst, and PANSTARRS (C/2013 X1) put on a nice show in June for those in the southern United States, the rest of us have had to snack on comets that barely reached 11th magnitude. The good news is that we’re heading toward a feast late this winter. Astronomers expect three icy visitors to come within range of binoculars and five to shine brighter than 10th magnitude.

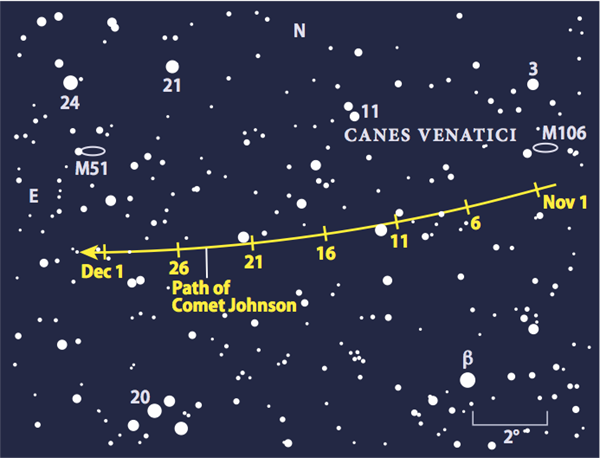

Treat this month’s ration as training that will help you get the most out of the upcoming banquet. Comet Johnson (C/2015 V2) should glow at 12th magnitude as it moves eastward through Canes Venatici, a constellation that climbs halfway to the zenith in the northeastern sky as dawn breaks. The comet begins November just 1° south of spiral galaxy M106 and finishes the month 3° south of the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51).

Begin with quick looks at these two Messier galaxies. Then, hop over to the comet’s position. Unless you have a large telescope, the faint fuzzball won’t be visible at low power. Start at 150x or so, take a few minutes to get accustomed to the darker field, and then begin scanning. Nudge the tube occasionally to trigger the motion-sensitive rods of your peripheral vision.

Once you locate Johnson, bump up the power again to look for detail. The comet likely will appear out of round with a better-defined southern flank. Once you’ve examined this visitor, you’ll be ready to dive into the structure of next month’s Comet 45P/Honda-Mrkos-Pajdusakova.

Ceres puts on a Whale of a show

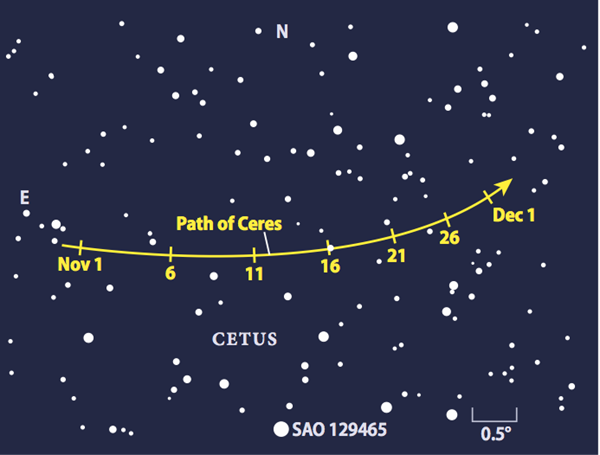

So big that astronomers now also classify it as a dwarf planet, asteroid 1 Ceres spends November gliding westward through the sparse star fields of north-central Cetus. The 600-mile-wide object reached opposition and peak visibility in late October, so it is now perfectly placed in the southern sky during late evening. Although Ceres fades from magnitude 7.5 to 8.1 this month, it remains among the brightest objects floating above the Whale’s back.

The meager background means that it will take some effort to find the asteroid by star-hopping. Start with Theta (θ) and Zeta (ζ) Ceti, a pair of 4th-magnitude stars on the Whale’s back. They lie 7° apart, about the width of a typical finder field. Then, shift the same distance north-northwest of Zeta to locate magnitude 5.0 SAO 129465, the brightest star on the chart below. Ceres lies a couple of degrees farther north throughout November.

Most of the background stars are considerably fainter, particularly during the month’s second half. If you still aren’t sure which point of light is Ceres, return to the same field a night or two later and pick out the object that shifted position. Ceres passes through a wide, right-angled triangle of fainter stars from November 17–19, an opportunity to notice its movement during a single evening.

Ceres is not alone — the Dawn spacecraft is circling it and taking lots of pictures. It’s so small, however, that even Hubble can’t see it.