But its job is not done yet. On August 11, Fermi entered an extended phase of its mission — a deeper study of the high-energy cosmos. This is a significant step toward the science team’s planned goal of a decade of observations, ending in 2018.

“As Fermi opens its second act, both the spacecraft and its instruments remain in top-notch condition, and the mission is delivering outstanding science,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division in Washington, D.C.

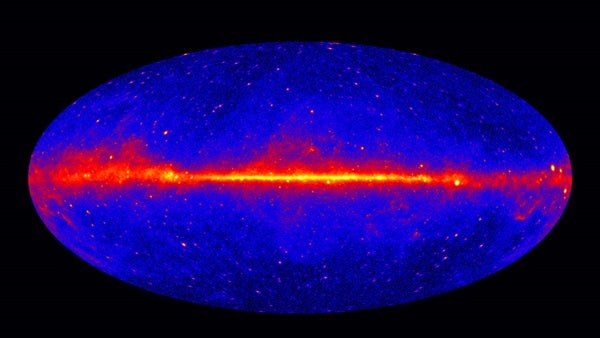

Fermi has revolutionized our view of the universe in gamma rays, the most energetic form of light. The observatory’s findings include new insights into many high-energy processes, from rapidly rotating neutron stars, also known as pulsars, within our own galaxy, to jets powered by supermassive black holes in faraway young galaxies.

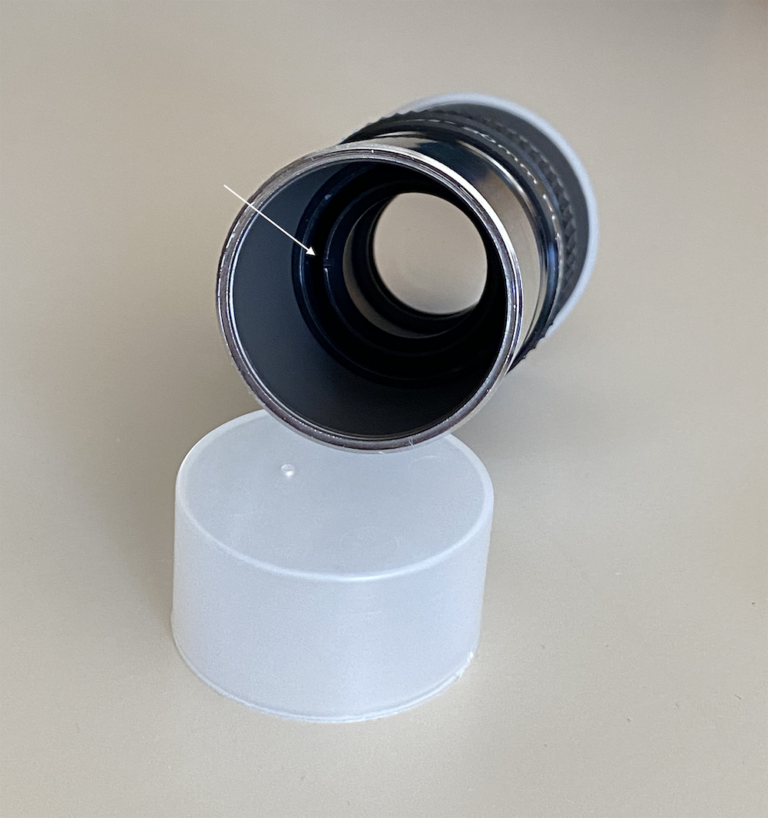

The Large Area Telescope (LAT), the mission’s main instrument, scans the entire sky every three hours. The state-of-the-art detector has sharper vision, a wider field of view, and covers a broader energy range than any similar instrument previously flown.

“As the LAT builds up an increasingly detailed picture of the gamma-ray sky, it simultaneously reveals how dynamic the universe is at these energies,” said Peter Michelson from Stanford University in California.

Fermi’s secondary instrument, the Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM), sees all of the sky at any instant, except the portion blocked by Earth. This all-sky coverage lets Fermi detect more gamma-ray bursts, and over a broader energy range, than any other mission. These explosions, the most powerful in the universe, are thought to accompany the birth of new stellar-mass black holes.

“More than 1,200 gamma-ray bursts plus 500 flares from our Sun and a few hundred flares from highly magnetized neutron stars in our galaxy have been seen by the GBM,” said Bill Paciesas from the Universities Space Research Association’s Science and Technology Institute in Huntsville, Alabama.

The instrument also has detected nearly 800 gamma-ray flashes from thunderstorms. These fleeting outbursts last only a few thousandths of a second, but their emission ranks among the highest-energy light naturally occurring on Earth.

One of Fermi’s most striking results so far was the discovery of giant bubbles extending more than 25,000 light-years above and below the plane of our galaxy. Scientists think these structures may have formed as a result of past outbursts from the black hole — with a mass of 4 million suns — residing in the heart of our galaxy.

To build on the mission’s success, the team is considering a new observing strategy that would task the LAT to make deeper exposures of the central region of the Milky Way, a realm packed with pulsars and other high-energy sources. This area also is expected to be one of the best places to search for gamma-ray signals from dark matter, an elusive substance that neither emits nor absorbs visible light. According to some theories, dark matter consists of exotic particles that produce a flash of gamma rays when they interact.

“Over the next few years, major new astronomical facilities exploring other wavelengths will complement Fermi and give us our best look yet into the most powerful events in the universe,” said Julie McEnery from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.