You’ll find the name Neil Armstrong in any historical listing of the world’s greatest explorers. No one would quarrel with the Apollo 11 commander, test pilot and first man on the Moon being high on that list. Except Armstrong, that is.

He saw himself as an engineer first.

In an early interview for my biography of Armstrong, he expressed the raison d’être of his career in flight: “I flew to the Moon not so much to go there, but as part of developing the system that would allow it to happen.”

He once told the National Press Club: “I am, and ever will be, a white-socks, pocket-protector, nerdy engineer, born under the second law of thermodynamics, steeped in the steam tables, in love with free-body diagrams. … Science is about what is. Engineering is about what can be.”

He did accept being called a pioneer, because he knew the word connected etymologically to engineering. Popular culture long portrayed American pioneers as Daniel Boone or Davy Crockett, wearing buckskins, fighting off Shawnee warriors or Red Sticks, and opening the way to settlements on the western frontier.

But the English word pioneer has a long history. The word ultimately derives from the Medieval Latin word pedo (as in our English word pedestrian). In ancient times, pedones were foot soldiers whose job was to build and repair roads for the main body of troops. They were engineers, members of a construction corps who prepared the way for the main army.

Armstrong’s stock-in-trade was in league with his fellow pedones, paving the way.

Once, over lunch, I asked him to compare the Moon landings to another event in human history. I thought, being an engineer, he would cite an invention — the wheel, the compass, the steam engine, the transistor. But, as happened so often, his quick answer surprised me: “the Austronesian expansion.”

He had just read Jared Diamond’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book Guns, Germs, and Steel, which offers a bold and sweeping explanation of why Eurasian and North African civilizations survived and conquered others, due to geographical and environmental advantages rather than intellectual, moral or genetic superiorities. It was clear Armstrong admired the thesis, but he was focused on one chapter in particular: “Speedboat to Polynesia.”

Archaeologists have found that groups of people were leaving Asia by boat tens of thousands of years ago, and by 5000 B.C., these immigrants had established a potent and versatile culture on the island of Taiwan (also once known as Formosa), combining fishing, gardening and a little farming.

But their migration was hardly over, Armstrong explained. Around 2500 B.C., having mastered ocean navigation by plying the water between Taiwan and the coast of Asia, these enterprising, seagoing people — the Austronesians — spread out into the Philippine islands. From there, they ventured even farther into the vast Pacific, which covers about one-third of Earth’s entire surface. The Pacific islands the Austronesians came to settle — eventually all the way to Hawaii and Easter Island — are like grains of sand scattered across a vast blue void. To think that a people could navigate the Pacific well enough to settle and establish culture on islands separated by so much ocean is truly extraordinary, Armstrong said. Yet somehow early humans managed to reach them all.

I asked Neil if he saw the Austronesian expansion as a forerunner for how humankind will become a true spacefaring civilization.

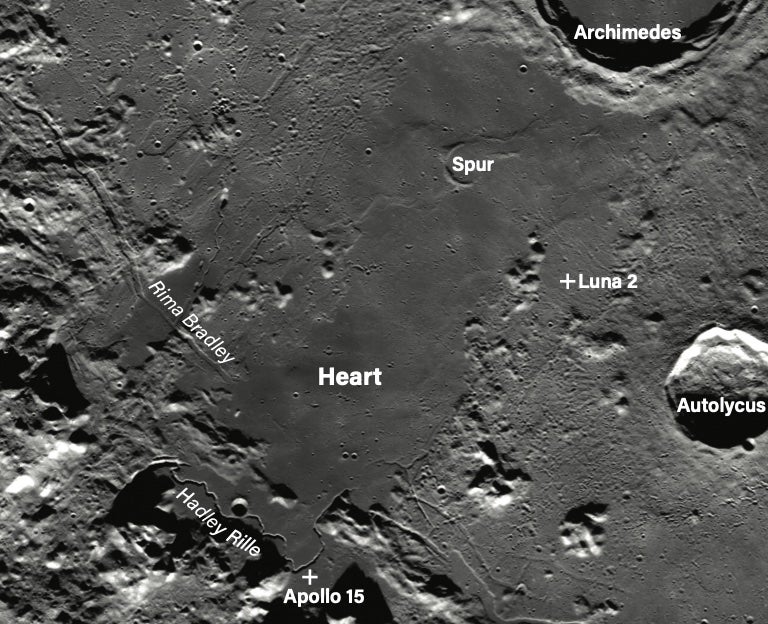

“Yes, I do,” he said. “We have learned how to navigate to the Moon. That is like the ancient Chinese mainlanders learning how to get to Formosa; Formosa is the Moon. After we settle it, we jump off from there to Mars, just like they went next to the Philippines. And from there, all across our vast galaxy. If the Austronesians can sail in their boats and scatter into settlements all across Oceania, we can take our spacecraft and scatter and settle all across the Milky Way.

“It may take even longer than it took the Austronesians, but if they did it, so can we,” he said. “Because they are us.”