On August 4, 1826, Scottish astronomer James Dunlop discovered what would prove to be a puzzle for the ages. While observing with his 9-foot reflecting telescope from Parramatta, New South Wales, Dunlop found what he later described as “a very singular double nebula. … These two nebulae are completely distinct from each other, and no connection of the nebulous matters between them.” A singular double nebula? Sounds more like an astronomical oxymoron than an observation. What had Dunlop found?

Dunlop’s riddle is now known as Centaurus A (NGC 5128), a fascinating galaxy in the southern constellation Centaurus the Centaur. When we look at Centaurus A, we are looking at a case of galactic cannibalism. Inside the heart of this huge elliptical galaxy lies a massive black hole that is consuming a smaller spiral galaxy. The two are believed to have collided between 160 and 500 million years ago.

Your binoculars won’t detect any of the internal strife that Centaurus A is enduring, but they can show you this intergalactic enigma that continues to fascinate astronomers — that is, if you can see the galaxy at all. The problem is that Centaurus A lies 43° south of the celestial equator, and so it is always confined to the far southern sky for most of the Northern Hemisphere. It never rises more than 7° above my own horizon here on Long Island (40° north latitude). Farther north, its maximum altitude shrinks; travel southward and Centaurus A will climb higher in the sky.

Overlooking the Atlantic Ocean along Long Island’s south shore, I can just make out Centaurus A through my 10×50 binoculars. It’s tough, but by waiting until it lies on the meridian and is highest in the sky, it’s unmistakable.

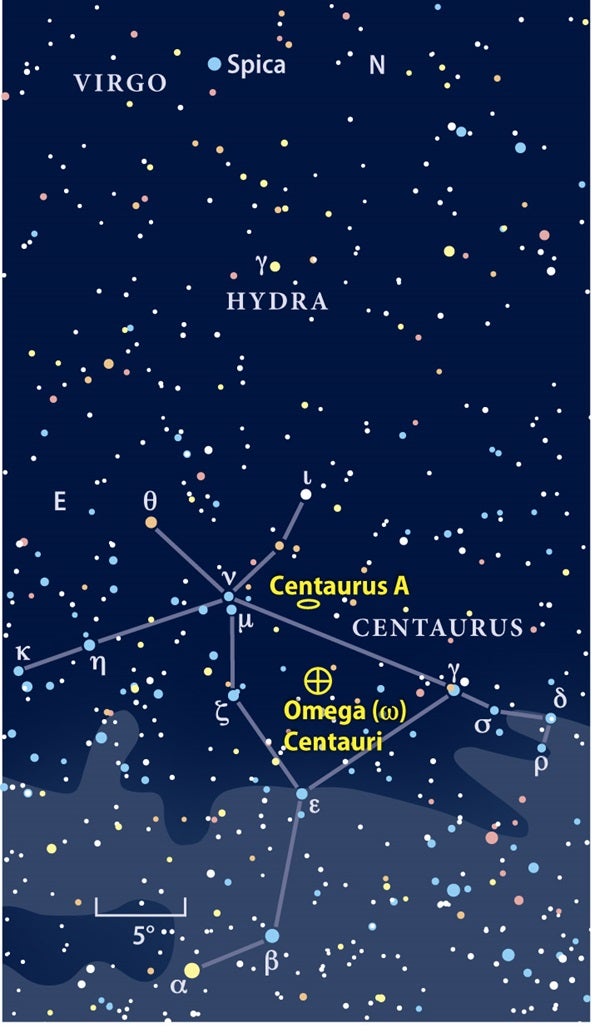

As luck would have it, the bright star Spica (Alpha [α] Virginis) has nearly the same right ascension as the galaxy, so we can use it as a guide. Scan about 12° (two fields of view) straight southward from Spica to 3rd-magnitude Gamma (γ) Hydrae. Another 13° farther south, you will come to 3rd-magnitude Iota (ι) Centauri. It won’t be long now.

If you found Centaurus A, then the night sky’s grandest globular cluster of all, Omega (ω) Centauri (NGC 5139), lies just 4½° farther south. Can you spot it, too? I’ve seen 2nd-magnitude Zeta (ζ) Centauri, which lies at the same declination as Omega, from Long Island but never the cluster itself.

From a vantage point that places it high in the sky, Omega Centauri is a sight to behold. The finest view I have ever had was from the Winter Star Party in the Florida Keys several years ago. It was absolutely stunning! My first thought when I saw it: It’s huge! I could resolve some of its estimated 1 million stars with 11×80 binoculars, while a “not-quite-resolved” grainy appearance was plainly evident through 10x50s. Regardless of the instrument used to spot it, you’ll remember your first encounter with Omega Centauri for a lifetime.

This month concludes my “Binocular Universe” column here in Astronomy magazine. I hope you have enjoyed the journeys we have shared over these past 4 years and that you will continue to tour the universe through binoculars far into the future. Let’s keep in touch. Drop me a line at phil@philharrington.net and share your observations. And until we meet again somewhere under the stars, remember that, now as always, two eyes are still better than one.

More southern-sky treasures.

April 2009: Comb through Coma Berenices

See an archive of Phil Harrington’s binocular universe