To find the best magnification for the Red Planet on a given night, start with a low-power eyepiece and then increase the magnification to roughly 20 to 25 times the telescope’s aperture in inches. (For example, shoot for about 160x if you use an 8-inch telescope). This should give you a crisp view with enough magnification to see plenty of detail. Continue trying successively higher-power eyepieces until increasing the magnification shows no more detail. Back off to the previous eyepiece and you should have an aesthetically pleasing view with as much detail as your telescope and the night’s conditions allow.

The best optics in the world won’t do much good if you have to battle a lot of turbulence in Earth’s atmosphere. A nice steady atmosphere, what observers commonly refer to as “good seeing,” is just as important for getting sharp views — particularly when Mars rides low in the sky and its light has to pass through more air than normal.

Although you might think that the state of the atmosphere lies well beyond your control, that’s only partially true. If you observe Mars when it’s at its highest, you won’t be looking through as much of the atmosphere. You can also improve the local seeing significantly by choosing an observing site in an open grassy area or looking over a large body of water. Avoid obvious heat sources, such as concrete buildings and asphalt parking lots, that soak up the sun’s heat during the day and release it at night. Letting your telescope cool down to the ambient air temperature for 30 to 60 minutes before observing will also help.

Finally, experienced Mars observers swear by a good set of color filters. An orange (Wratten #21 or #23A) filter or a red (#25 or #29) filter works best for showing the ubiquitous dark surface markings. These filters brighten the orange-red deserts and darken the markings, enhancing contrast in the process. Green (#56, #57, and #58) and blue (#38, #38A, or #80A) filters will emphasize the polar caps and bring out any fog, haze, or clouds in the planet’s thin atmosphere.

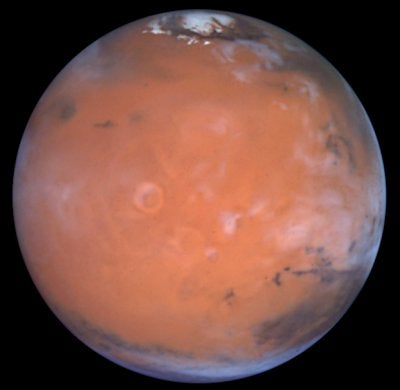

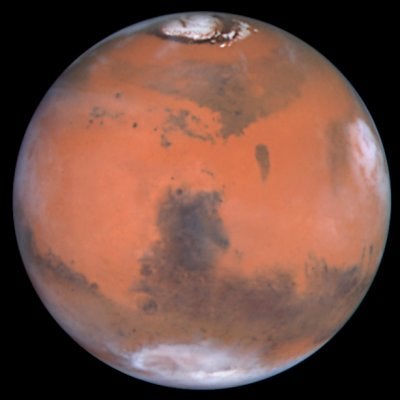

No other features on Mars stand out like the polar caps. Consisting of water ice and frozen carbon dioxide (dry ice), the caps glow bright white and appear conspicuous whenever they face Earth. Even a small telescope will let you see them wax and wane with the planet’s changing seasons.

Mars experiences seasons much like those on Earth because its axis tilts 25&mdeg; to the plane of its orbit around the sun, just 2&mdeg; more than the tilt of Earth’s axis. The only major differences: Martian seasons last nearly twice as long as those on Earth because the planet’s year equals nearly two Earth years, and seasons in the southern hemisphere of Mars are more severe because the planet always lies farther from the sun when it’s winter in the south and closer to the sun when it’s summer.