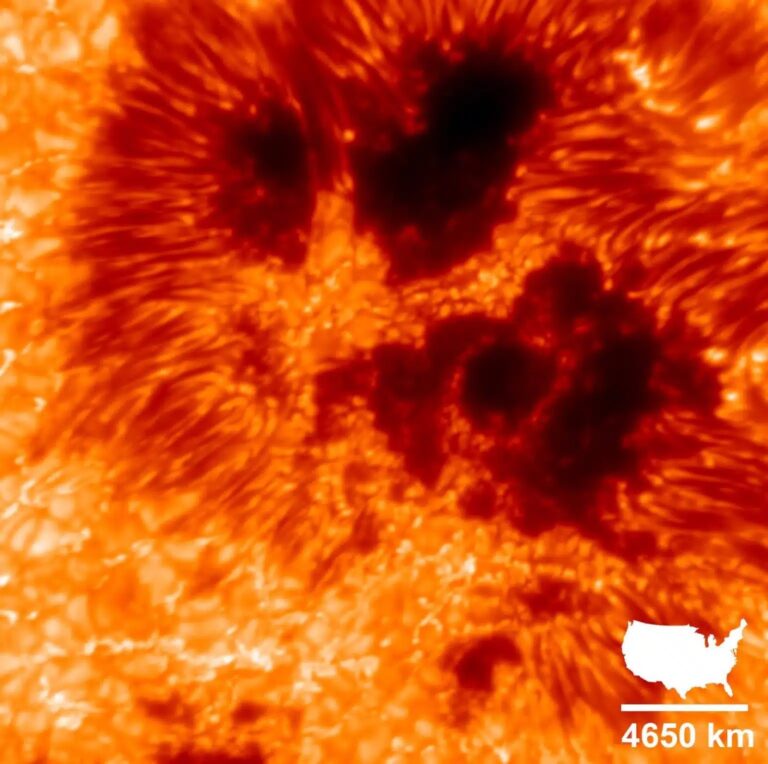

It wasn’t the scope. Susan would soon learn that the finest optical instruments in the world play second fiddle to that fickle element that starlight first encounters: Earth’s atmosphere. The ever-changing ocean of air surrounding our planet can be calm or turbulent, clear or murky — dramatically affecting what we ultimately see at the eyepiece.

The steadiness of our atmosphere is known as “astronomical seeing.” Good seeing is paramount for sky objects that require high power, like the Moon, the planets, and narrowly separated double stars. If the air is calm, you can use the maximum possible magnification your telescope will allow. Throw in some atmospheric turbulence, however, and you’ll experience what Susan saw the night she christened her telescope.

A slew of factors contribute to seeing conditions, from global weather patterns to air currents inside the tube of a telescope that hasn’t yet adjusted to the outside temperature. Heat waves rising from the ground after sunset or from dwellings on cold evenings can also produce annoying ripples.

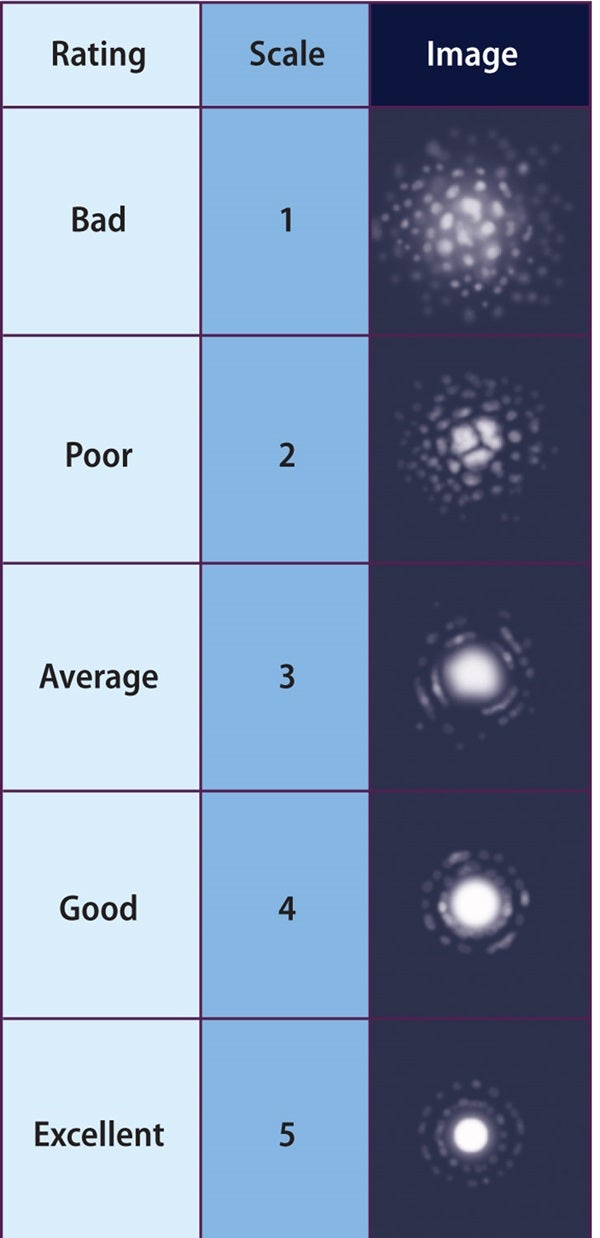

Of the various scales devised to rate seeing, I find the 1 (terrible) to 5 (ideal) particularly useful for basic backyard astronomy. You can get a “ballpark” estimate of seeing simply by looking up and noting how rapidly stars twinkle.

A more precise way to assess seeing conditions is to look at the image of a bright star under high magnification. If it “boils” incessantly, rate the seeing as 1. If the image is crisp and surrounded by unwavering concentric circles (diffraction rings), the seeing is a 5.

A simple way to evaluate transparency is to gaze at a portion of the sky roughly halfway up from the horizon and note the whole number magnitude of the faintest star visible. This produces a scale from 0 (totally overcast) to 6 (the faintest star traditionally visible from a dark-sky location). In remote areas, the scale can even extend beyond 6. If you rate the transparency as 7 or even 8, you’re in the Australian Outback, mate!

The angle above the horizon of the object you’re observing also affects seeing and transparency. From the zenith (overhead) to the horizon, transparency decreases (atmospheric extinction) because you’re looking through a thicker column of air. Seeing similarly suffers.

It’s an astronomical fact of life that good seeing and transparency rarely go hand-in-hand. A night of exceptional seeing is often accompanied by poor transparency, and vice versa. In mid latitudes, we experience some of the best seeing during the warm, hazy nights of summer, while cold winter evenings bring transparent, but often turbulent, skies. During the transition periods of spring and fall, we can get a delicious

mix of either.

Whatever the season, you’ll want to learn to evaluate the sky conditions and then adapt. If the seeing is good, target the Moon and planets or that close double star you’ve never been able to notch. Transparent skies give you a chance to ferret out faint galaxies or nebulae.

From our great ideas department comes a suggestion from Joe Shuster of Gurnee, Illinois. In reference to my article on astronomical awards in the April 2008 issue of Astronomy, he writes: “I think it’s more fun giving awards than getting them.” His club, the Lake County Astronomical Society, presents “Lake Sky Star Awards” to non-astronomers who do things that promote astronomy. When a car dealership agreed to temporarily reduce its lighting so it wouldn’t disrupt the society’s star party at a local school, the club gave the dealer an award.

For more information, go to www.lcas-astronomy.org, and click on “Lake Sky Star Awards.”

October 2008: See the red star round-up

December 2008: X-rated astronomy

See an archive of Glenn Chaple’s observing basics