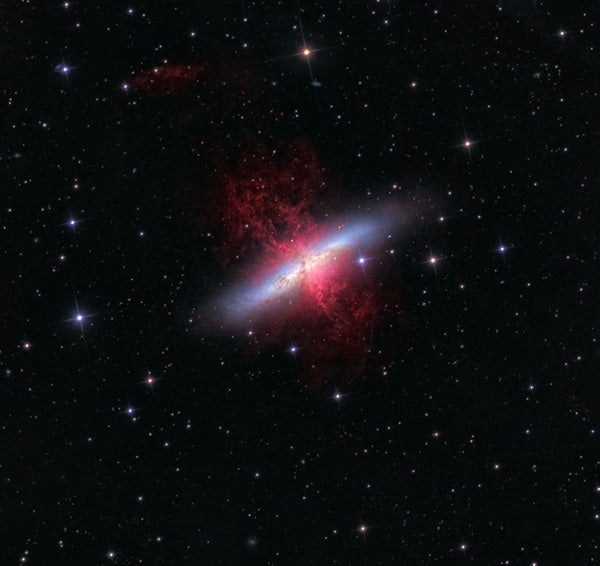

Of those, my favorites are a celestial version of The Odd Couple: M81 and M82 in Ursa Major. Nowhere else in the sky do we find such an unusual pair. On one hand, we have a textbook example of a spiral galaxy. Like Felix Unger, it appears neatly arranged and well groomed. On the other, we have Oscar Madison, an unkempt, disheveled galactic mess.

Like Felix and Oscar, they live right next to each other in space, and have an undue influence on each other’s existence — some good, some bad.

The Felix Unger of the pair is M81, a model Sb spiral system. The galactic arms in Sb spirals are wound moderately tightly around their galactic core. Color photographs show a bluish-white tint to those arms due to the many young, scorching stars found within. The core appears yellowish, a telltale sign of more mature stars.

Through binoculars, M81 looks distinctly oval due to its tilt from our vantage point. Centered within that oval glow lies the galactic core, appearing like a faint, buried star.

Then we have the Oscar Madison of the couple, M82. Bode is also credited with its discovery in 1774. He probably didn’t notice it at first, since M82 is about a magnitude fainter than M81. But he eventually glimpsed it, and so can you. Glance about half a degree north of M81. M82 looks long and thin, somewhat like a sausage. With patience, I’ve spotted it through 7×35 binoculars under suburban skies.

Nicknamed the Cigar Galaxy for its stogie-like shape, M82 is often cited in books as the quintessential example of an irregular galaxy. But all that changed in a paper titled “The Discovery of Spiral Arms in the Starburst Galaxy M82” in the July 2005 issue of The Astrophysical Journal. Examining images of M82 taken at near-infrared wavelengths, authors Y. D. Mayya, L. Carrasco, and A. Luna noted that we are seeing M82 nearly edge-on. That challenging orientation plus the “high disk surface brightness, and the presence of a complex network of dusty filaments in the optical images are responsible for the lack of detection of the arms in previous studies.”

Before we close, let’s leave intergalactic space and bring it back home for a look at the variable star R Ursae Majoris. R UMa, about 4.5° due east of M81, is a long-period variable, like Mira in autumn’s constellation Cetus. These pulsating red giants throb with enviable regularity. Over 302 days, R UMa goes from a maximum brightness of about 7th magnitude down to less than 13th, and then back again. Right now, it’s on the way up. Maximum brightness is expected to occur in June or early July, so be sure to keep an eye on it.

Have a favorite binocular target that you’d like to share with us? I’d love to feature it in a future column. Drop me a line through my website, philharrington.net.

Until next time, don’t forget that two eyes are better than one.