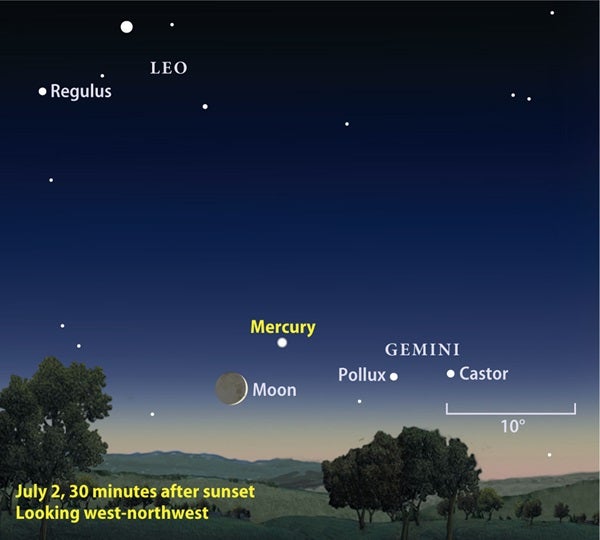

Let’s start our tour of solar system delights where we normally do, in the western sky at dusk. Shining at magnitude –0.4, Mercury pops out of the twilight glow just as the sky starts to darken. Look for it July 2, when it stands 8° above the horizon 30 minutes after sunset and 5° north of a slender crescent Moon. Our satellite sets around 9:30 p.m. local daylight time and the planet follows some 20 minutes later. Point a telescope at the inner world, and you’ll see a gibbous disk spanning 6″.

Mercury’s next impressive conjunction comes July 6, when it crosses the Beehive star cluster (M44) in Cancer the Crab. The pair’s low altitude makes seeing the cluster a challenge even through binoculars. Your chances increase if you live farther south, where the two appear higher and in a darker sky.

Mercury reaches greatest elongation July 19/20, when it lies 27° east of the Sun. It won’t be any easier to see from the Northern Hemisphere than it was early in the month, however, because its brightness dips (to magnitude 0.3) and its altitude remains nearly the same. A telescope does reveal a more interesting disk, one that measures 8″ across and has a fat crescent shape.

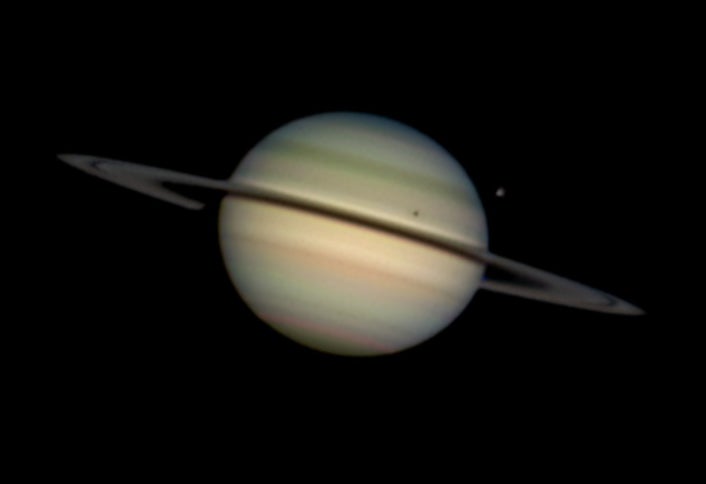

About an hour after sunset, Saturn appears as a bright dot one-third of the way from the southwestern horizon to the zenith. The golden-colored planet lies nearly 15° to the right of blue-white Spica, Virgo the Maiden’s luminary, and shines a hair brighter than the 1st-magnitude star.

The view of Saturn through a telescope is never less than stunning. The planet’s disk spans 17″, and the ring system stretches 39″ from tip to tip. The rings start to become more noticeable this month as they tip more to our line of sight. In June, the tilt slimmed to 7°, its minimum for 2011. The tilt grows to 8° by mid-July and to 15° by year’s end.

While we’re on the subject of interesting angles, Saturn reaches quadrature July 2/3. To understand this configuration, imagine looking down on the solar system from far above. At quadrature, a line drawn from the Sun to Earth and then to Saturn forms a 90° angle. To observers, this means the shadow cast by Saturn falls as far east of the planet as possible and hides a noticeable section of the rings’ farside from view.

Any telescope will show you Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The 8th-magnitude satellite orbits the ringed planet once every 16 days. For North American observers, Titan lies farthest east of Saturn July 1 and 17, and farthest west July 9 and 25.

A 4-inch scope reveals a trio of 10th-magnitude moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — with smaller orbits than Titan. Farther out lies two-faced Iapetus. This satellite shines at 10th magnitude when it’s farthest west of Saturn, as it was in early June. The moon passed north of the planet June 30 on its way toward greatest eastern elongation, which occurs July 20. Iapetus then glows at 12th magnitude and will be a challenge to see through an 8-inch scope. It lies some 8′ from Saturn, 5 times farther east of the planet than Titan.

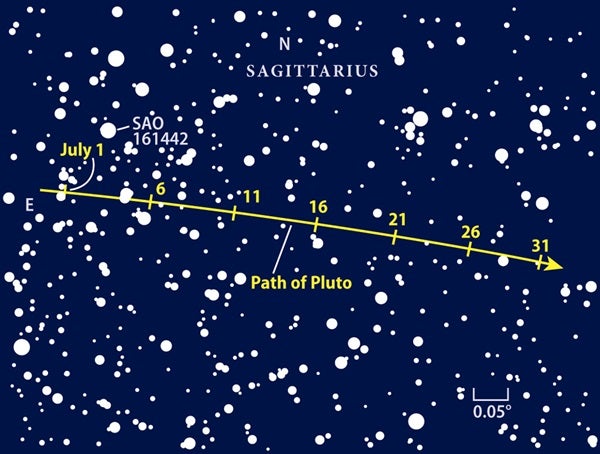

Distant Pluto reached opposition and peak visibility in late June, so it remains a tempting (although challenging) target in July. It glows at 14th magnitude, which puts it within range of a 10-inch telescope on a clear, dark night. You can find Pluto about 2° west of the bright open star cluster M25 in northern Sagittarius. The best guide star in the planet’s immediate vicinity is 9th-magnitude SAO 161442. Pluto slides 0.1° south of this star during July’s first week.

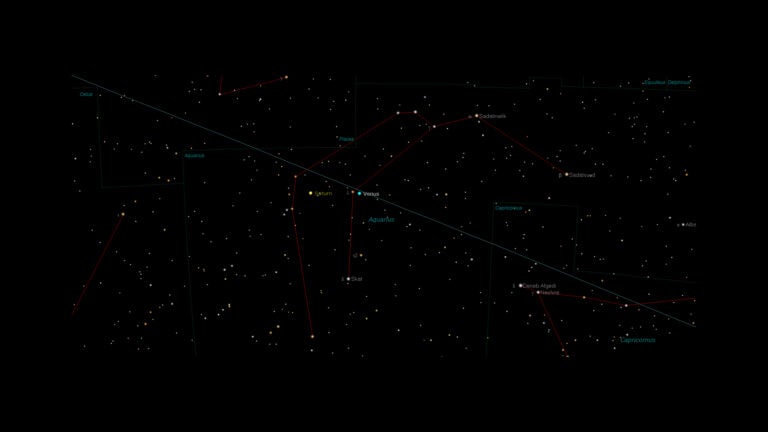

Neptune glows at magnitude 7.8, so it’s easy to pick out through binoculars. First, find 5th-magnitude 38 Aquarii, the brightest star along a line joining 4th-magnitude Theta (θ) and Iota (ι) Aquarii. Neptune passes 0.3° (half of the Full Moon’s width) south of 38 Aqr during July’s second week. Turn a telescope on Neptune, and you’ll see a blue-gray disk that spans 2.3″.

Uranus lies one constellation east of Neptune in a star-poor region of Pisces the Fish. But you should start your search for Uranus with a more conspicuous asterism: the Great Square of Pegasus. Draw a line from Alpheratz, the square’s northeastern corner, to Algenib, the southeastern corner. Then, extend this 14°-long line another 14° to the south. Uranus will be right there. Although this area clears the eastern horizon by midnight local daylight time, you’ll get a better view if you wait until dawn approaches.

Although Uranus shows up to naked eyes under a dark sky, binoculars are better for hunting it down. Just don’t confuse the planet with a pair of stars less than 1° to its north. Uranus glows at magnitude 5.8, slightly brighter than either star. Through a telescope, the planet displays a 3.6″-diameter disk with a distinct blue-green color.

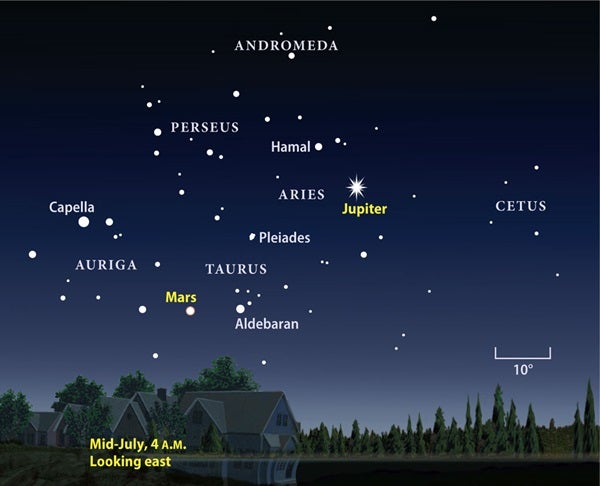

The king of the planets, Jupiter, certainly lives up to its name this month — no other world shines as brightly in a dark sky or appears as large through a telescope. The giant planet lies in southern Aries the Ram and rises around 2 a.m. local daylight time July 1 (it peeks above the horizon 2 hours earlier by month’s end). The best views come when it climbs higher in the hour or two before twilight begins.

You can also follow Jupiter’s four bright moons through any scope. These worlds constantly change their positions as they circle the planet at different rates. Innermost Io moves fastest, orbiting the planet once every 1.77 days. Europa, which is in an orbital resonance with Io, orbits in twice that period (3.55 days), while Ganymede orbits in twice Europa’s period (7.15 days). Outermost Callisto takes 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter, slightly longer than double Ganymede’s period.

A Last Quarter Moon stands to Jupiter’s upper right July 23. It’s a fine sight with naked eyes in the hour before dawn, especially when the stars associated with winter reappear above the eastern horizon. Taurus the Bull reminds us that these balmy summer nights eventually will give way to a harsher season.

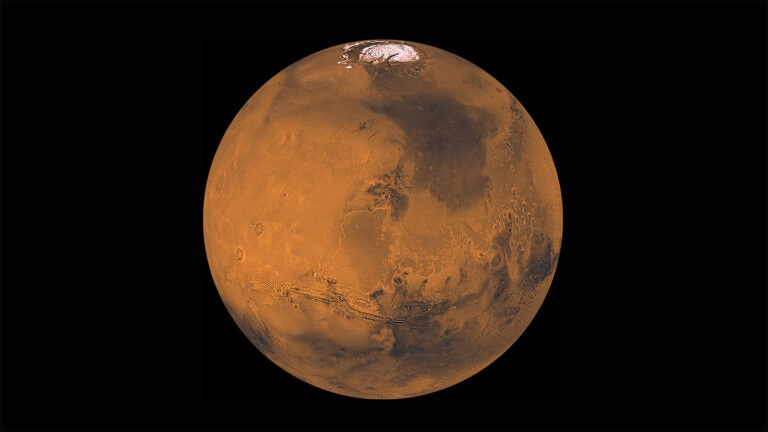

Taurus looks different this month because Mars is in its midst. On the morning of July 6, Mars lies 5° north of Aldebaran, the Bull’s brightest star and a near match to the Red Planet’s color. Shining at magnitude 1.4, Mars appears slightly fainter than the star. The planet’s disk spans just 4″ and shows no detail through a telescope. Still, its trek across Taurus during July will be fun to watch. It passes between the horns of the Bull July 26 and, a day later, teams up with a slim crescent Moon for a nice morning scene.

Venus appears low in the east-northeast before dawn in early July. It shines brilliantly at magnitude –3.8, the only reason it shows up in the bright twilight. Venus disappears in the Sun’s glow after July’s first week, and it will remain out of sight until late September.

A partial solar eclipse occurs July 1, but few people are likely to see it. The Moon’s shadow touches Earth only in a small region between Antarctica and South Africa. And the eclipsed Sun hovers just above the northern horizon in the Southern Hemisphere’s winter sky. The eclipse reaches maximum at 8h40m Universal Time, when the Moon blocks 10 percent of the Sun.

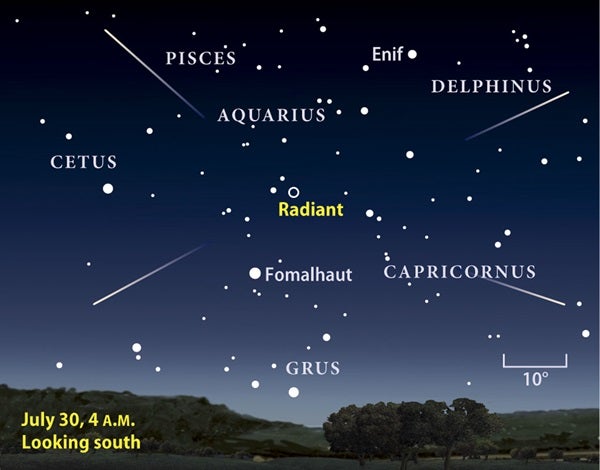

One of the year’s most prolific meteor showers, the Southern Delta Aquarids, reaches its peak July 30. The Moon obliges observers by reaching its new phase the same day, making for ideal conditions. The meteors appear to radiate from the constellation Aquarius the Water-bearer, which rises in late evening and climbs highest in the hours before dawn.

Although the Delta Aquarids produces a lot of meteors while it’s active from July 12 to August 23, it doesn’t produce the high peak rates some other showers do. At its best, you can expect to see an average of between 15 and 20 meteors per hour under excellent conditions. Fortunately, those rates remain nearly constant for a day or two on either side of the peak. For the best views, find an observing site far removed from city lights.

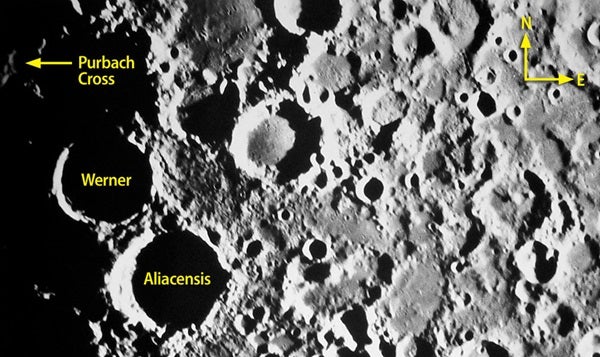

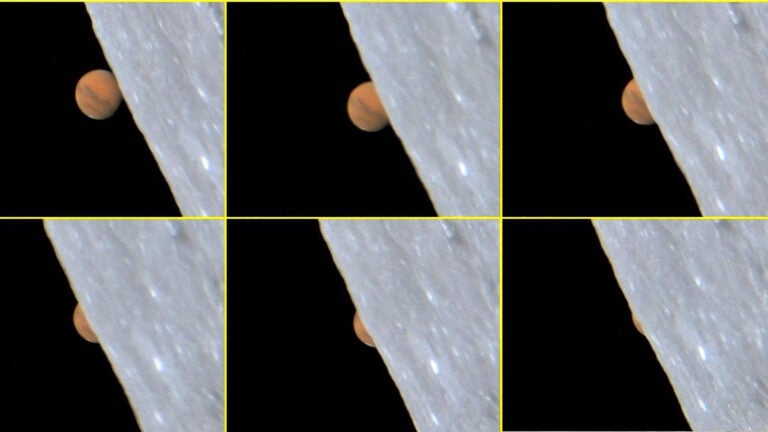

Observers in the western half of North America have a great opportunity this month to watch a few points of light on the Moon’s surface evolve into a prominent letter X. This feature carries the unofficial titles of Purbach Cross and Werner X, both of which refer to nearby named craters.

Set up your scope shortly after sunset July 7. As the sky darkens, target a region along the lunar terminator (the dividing line between light and dark) and focus on a spot about halfway between the equator and the south pole. You should have no trouble picking out the craters Aliacensis and Werner. These near twins serve as your guide to the X, which lies just to their northwest.

In just a few hours, you can see the X emerge, peak, and disappear. It’s mesmerizing to watch the rising Sun transform the appearance of a group of crater walls. You also might consider taking a series of images with a digital camera or webcam. With one shot every 5 to 10 minutes, you can create a time-lapse movie of the X’s evolution.

Oddly enough, the craters that form the X don’t show up on a night when the feature is visible. Only their high walls catch the first rays of morning sunlight. The individual craters — Blanchinus, la Caille, and Purbach — don’t come into full view until the following night. The photo above shows the region with the X just starting to emerge out of a sea of blackness.

From eastern North America, the X only begins to appear as the Moon sets. Observers there can take solace in enjoying myriad craters on the terminator as they evolve from arcs of light into full circles.

| When to view the planets | ||

| EVENING SKY | MIDNIGHT | MORNING SKY |

| Mercury (west) | Saturn (west) | Venus (northeast) |

| Saturn (southwest) | Uranus (east) | Mars (east) |

| Neptune (southeast) | Jupiter (east) | |

| Uranus (southeast) | ||

| Neptune (south) | ||

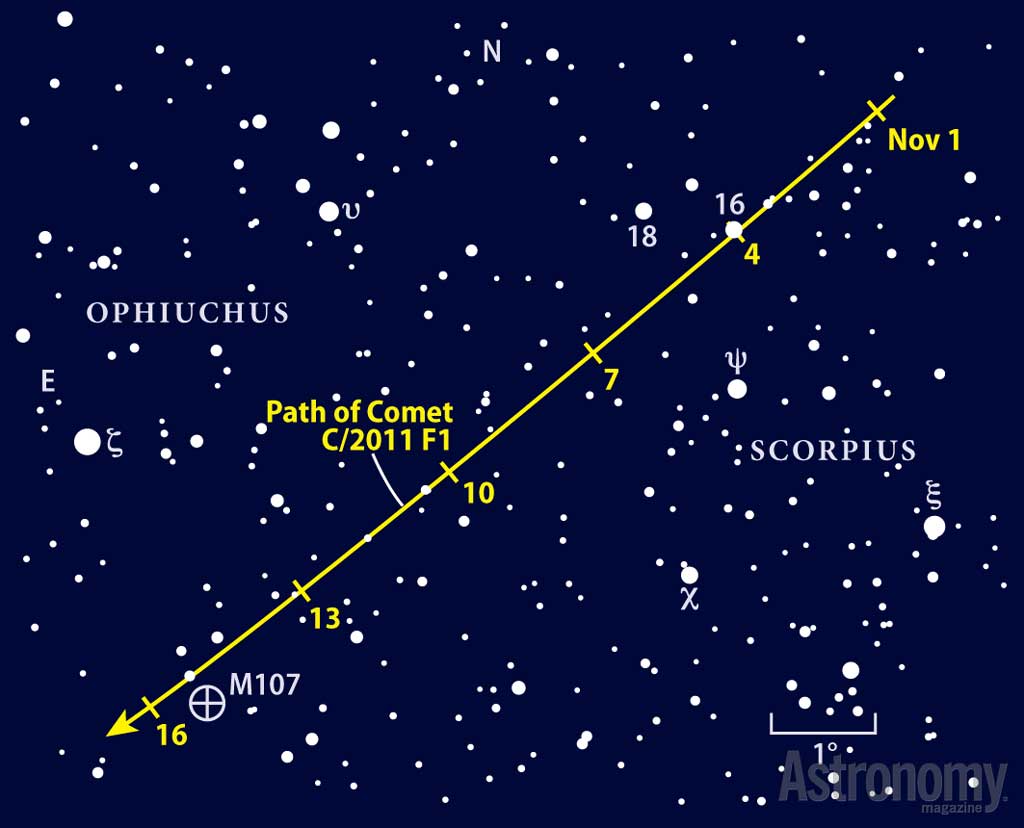

We are entering a long period of comet plenty following spring’s drought. Comet C/2009 P1 (Garradd) will take a year to sail through the inner solar system. It should remain a fixture in Northern Hemisphere skies from now until next summer. It currently glows around 8th magnitude and may peak near naked-eye visibility this winter.

You should be able to pick up this visitor from the distant Oort Cloud through a 4-inch telescope under a dark sky. From city suburbs, however, don’t expect to see much more than a faint fuzzy ball through an 8-inch scope. Comets making their first trip into the inner solar system are notoriously unpredictable, so don’t be surprised if Garradd glows 1 to 2 magnitudes brighter or fainter than expected.

This ancient ball of ice and dust rises in the east during the late evening hours and remains on view the rest of the night. It begins July just a couple of degrees northeast of the Water Jar asterism in the constellation Aquarius the Water-bearer. The two 4th-magnitude stars at the asterism’s eastern edge, Eta (η) and Zeta (ζ) Aquarii, appear at the bottom of the finder chart.

From there, the comet heads northwest through Pegasus the Winged Horse. It passes 2° north of 4th-magnitude Theta (θ) Pegasi during July’s third week and skims a similar distance north of 2nd-magnitude Enif (Epsilon [ε] Peg) at month’s end.

Like all comets, Garradd grows brighter as it approaches the Sun. Radiation from our star heats the ices in the comet’s nucleus until they turn directly to gas. The liberated molecules carry dust particles with them, which gives rise to a spherical shell around the nucleus that can span a million miles. The Sun’s ultraviolet light ionizes the gas molecules, and the solar wind then carries them away, forming a gas tail. Meanwhile, radiation pressure pushes the dust particles away from the Sun, creating a dust tail.

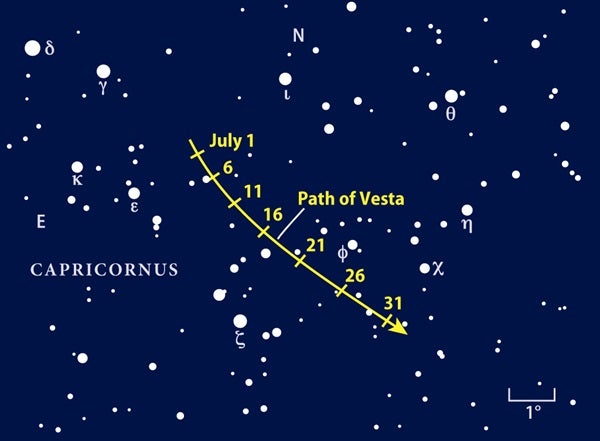

An asteroid that will be in the news later this summer puts on a nice show in July’s night sky. Vesta glows at 6th magnitude among the background stars of Capricornus the Sea Goat and is easy to see through binoculars. Vesta rises in late evening but becomes easier to find once it climbs higher after midnight.

At the beginning of July, Vesta forms the southern tip of an isosceles triangle with the 4th-magnitude stars Gamma (γ) and Iota (ι) Capricorni. It then heads southwest, passing a few modest stars, but not many that surpass the solar system’s brightest asteroid. Avoid looking between July 15 and 19, when a bright Moon passes north of Vesta.

Vesta reaches opposition and peak visibility in early August, when it will glow at magnitude 5.6. But the big story next month will be the arrival of NASA’s Dawn spacecraft at Vesta. The probe will orbit the third-largest asteroid until next May. Earth-based studies show that frozen lava covers Vesta’s surface, and a huge crater lies near the object’s south pole. After completing its Vesta reconnaissance, Dawn will fire its engines and head toward Ceres, the largest asteroid.

Martin Ratcliffe provides professional planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. Alister Ling is a meterologist for Environment Canada.