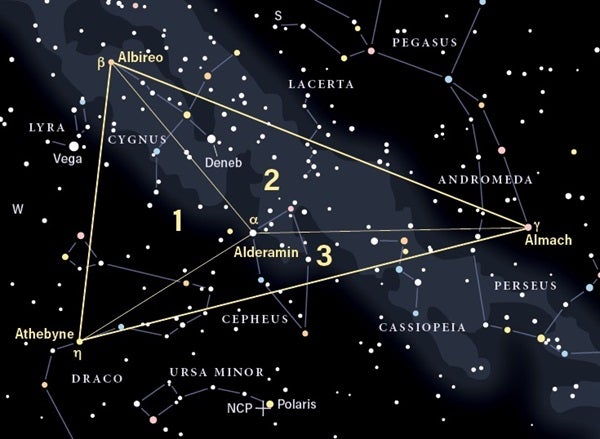

I’ve trisected the Golden Triangle into three smaller triangles of roughly equal area centered on Alderamin (Alpha [α] Cephei). Region 1 covers the area within the triangle formed by Athebyne, Alderamin, and Albireo. Region 2 covers the area within the Triangle formed by Albireo, Alderamin, and Almach. And Region 3 covers the area within the triangle formed by Almach, Alderamin, and Athebyne.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

▼ Region 1

Athebyne is a challenging binary system. The 3rd-magnitude yellow primary has a 9th-magnitude pip of light 5″ to the southeast. Try magnifications ranging from 200x to 300x in late twilight. A 2˚ sweep eastward brings us to the 12th-magnitude galaxy NGC 6223. While this highly concentrated (3.5′ by 2.5′) system may appear desolate, in high-resolution images it’s a mystifying concoction of warped spiral arms, a double nucleus, and an extended and misshapen outer elliptical halo.

Let’s return to Athebyne and look 6˚ east-southeast to find the binary star Struve 2155. The 7th-magnitude yellow primary has a 10th-magnitude blue companion 10″ to the east-southeast. This dim cousin to Albireo shares the same field of view with the mystifying orange giant star VW Draconis. In 1911, this star was listed as variable, ranging in photographic magnitude from 6.0 to 7.0 every 170 days, but it has since been “demoted” to a star of constant brightness. Take a look at it once a month for three or four months and see what you think. Now move about 10˚ east-southeast to 4.5-magnitude Omicron (ο) Draconis, a pumpkin orange star with an 8th-magnitude lavender companion some 34″ to the southwest.

Reversing direction, we drop our gaze to 4th-magnitude Iota (ι) Cygni, and look nearly 3˚ west-southwest for Struve 2486 — near twin yellow stars (magnitudes 6.6 and 6.8) separated by 8″. Its “big brother,” 16 Cygni, performs only 4½˚ to the east and slightly north, displaying two yellow 6th-magnitude stars separated by 40″. What’s more, the 9th-magnitude Blinking Planetary (NGC 6826) lies in the same field of view ½˚ to the east-southeast. The 30″-wide nebula displays a pale blue-green disk and appears to blink (swell and contract) as you alternate between averted and direct vision, respectively.

Let’s now center 4th-magnitude R Lyrae (also known as 13 Lyrae) in our telescopes and move 2˚ northeast to the 11th-magnitude face-on lenticular galaxy NGC 6703. This tiny glow with a bright core has a magnitude 13 elliptical companion, NGC 6702, about 15′ to its north-northwest; through an 8-inch telescope at moderate power, I first mistook the latter for a star because it’s so tiny (1.8′).

Zigging east-southeast to 3rd-magnitude Delta (δ) Cygni, we now look about 1¾˚ northeast for the 7th-magnitude open cluster NGC 6811. Popularly known as the “Hole in the Cluster,” this aptly named visual enigma looks, at a glance, like an amorphous smoke ring. But with more power, the smoke dissolves into a sparkling annulus of twinkling starlight. The cluster’s unusual distribution of stars — including a dense corona of brighter stars around the cluster’s center — explains the visual hole.

We end our tour of Region 1 by centering 4th-magnitude Theta (θ) Lyrae in our telescopes and looking about 1˚ east-southeast for the magnitude 9.5 open cluster NGC 6791. This galactic phantom’s pale and paltry stars span 16′ of sky. But don’t let that dissuade you from looking; German astronomer Friedrich Winnecke discovered this cluster using only a 3-inch telescope in 1853.

▼ Region 2

Our journey into Region 2 begins with a visual punch: beautiful Albireo, twin jewel of the north. This 3rd-magnitude golden gem has a 5th-magnitude emerald-blue companion 34″ to the northeast. Visual astronomers have adored it ever since they first turned their telescopes to it.

Once again we return to Delta Cygni, but hop 3½˚ east-southeast to another Caroline Herschel discovery: the Frigate Bird Cluster (NGC 6866). Shining at magnitude 7.5, this dynamic stellar aggregation displays about 130 stars of 10th magnitude or fainter across 16′ of sky. Splayed out in avian form (like its namesake), this long-tailed celestial “bird” even has a throat pouch of glittering stars.

Now look 3˚ to the north-northeast of NGC 6866 to 4th-magnitude Omicron1 Cygni, which has a 5th-magnitude line-of-sight companion 5.6′ to the northwest, making a great naked-eye test. But only 1.2˚ southwest of ο1 lies another small (7.5″) planetary nebula that glows at 11th magnitude. In a 3-inch refractor, it requires high magnifications to perceive its pale blue disk well; try 225x.

We now turn our attention about 8˚ north-northeast of Deneb (Alpha Cygni) to the “other” coalsack of Cygnus, Le Gentil 3. Near the northern shore of this 5˚-wide black lagoon we find the delightful Coatbutton Nebula (NGC 7008). At low power, the 10th-magnitude planetary nebula looks like a wide (100″) skirt of light dangling from a 9th-magnitude star. Use moderate magnification to spy its dark eyes at the core, which makes the nebula look like a button sewed onto the velvet sky.

Continuing our northeastward trek, we come to the stunning 4th-magnitude star Mu (μ) Cephei, otherwise known as Herschel’s Garnet star — one of the most brilliant of all the red giants and arguably the reddest star visible to unaided eyes. Less than 1½˚ south and slightly west is the 4th-magnitude Misty Clover Cluster (Trumpler 37) and its associated emission nebula IC 1396 (170′ x 140′), which together form the core of the Cepheus OB2 Association. This celestial delight has one more prize: 5.5-magnitude Struve 2816, a striking triple star system at the center of Tr 37. All the components reveal themselves admirably at 72x.

Returning to Delta Cephei, head about 3¼˚ north-northeast to the 12th-magnitude planetary nebula NGC 7354. At 60x, the nebula appears as a 20″ glow with a bright core and a ghostly, somewhat elongated outer halo. Moderate- to large-aperture telescopes and magnifications beyond 200x may reveal the collection of bright knots that girdle the nebula.

Our next object, Caroline’s Spiral Cluster (NGC 7789), lies 3˚ southwest of 2nd-magnitude Caph (Beta Cassiopeiae) and was discovered by — who else? — Caroline Herschel. Binoculars show it as a circular “cloud of minute stars” that sparkle in and out of view with averted vision. Telescopically, this magnitude 6.5 cluster spans 25′ of sky and is one of the finest and richest open clusters. The challenge is to see it with your unaided eyes.

Returning to Caph, we slide about 30′ south-southeast to find the tiny (5′) reflection nebula van den Bergh 1. This pale breath of light is illuminated primarily by three roughly 9th-magnitude stars, burning through the haze like streetlights seen through fog.

Now glide about 1¾˚ east and slightly north of vdB 1 to the 10th-magnitude dwarf irregular galaxy IC 10, a member of the Local Group of galaxies, and the closest known starburst galaxy. Knowing that it lies 2.2 million light-years away (closer than the Andromeda Galaxy) will help you to appreciate its tiny size (7′).

We begin our final region with our third golden double star, Almach. A gem for telescopes of all sizes, the 2nd-magnitude primary sports a 5th-magnitude sapphire companion 10″ away. Jumping northwestward to 5th-magnitude Phi (φ) Cassiopeiae, we arrive at the adorable Owl Cluster (NGC 457), one of the most popular showpieces at amateur gatherings and an object named by Astronomy Editor David J. Eicher. The magnitude 6 cluster has two prominent stars (Phi1 and Phi2) as its eyes, a roughly T-shaped arrangement of dimmer stars, and two isolated suns marking the owl’s feet.

Now let’s center Eta Cassiopeiae in our telescopes. Dubbed the Easter-Egg Double, the 3.5-magnitude topaz primary shares the field with a magnitude 7.5 lilac companion 13″ to the northwest. A short 1½˚ hop to the southeast brings us to another treasure: the irregularly shaped Pacman Nebula (NGC 281). The comma-shaped, 30′ glow contains a 4′-wide open cluster (IC 1590) at its core.

Next up is a triad of disparate clusters. We begin with the Widow’s Web Cluster (NGC 7790) about 2½˚ northwest of Caph. Although the cluster shines dimly at magnitude 8.5, its two dozen or so stars are compacted into a 5′-wide region of sky and appear as a highly concentrated east-west-trending Y-shaped web of starlight against a rich Milky Way backdrop. NGC 7788, a 9th-magnitude, 9′-wide cluster, lies only about 15′ to the northwest, while the 10th-magnitude open cluster Berkeley 58 is about 20′ to the southeast, looking like a 5′-wide ghostly gathering of minute stars.

Moving northward to 3rd-magnitude Gamma Cephei, we look about 5½° southeast for the 35″-wide disk of the Bow-tie Nebula (NGC 40). The 12th-magnitude planetary’s magnitude 11.5 central star overpowers the surrounding glow. Magnifications greater than 150x are required to perceive the dark cavity between the central star and its shell.

Let’s slip over to 3rd-magnitude Alfirk (Beta Cephei), then about 3° southwest to the 8th-magnitude Iris Nebula (NGC 7023) — a high-surface-brightness reflection nebula surrounding a 7th-magnitude star. Here is one of the first regions where astronomers found direct evidence of dust grains in molecular clouds.

Another 3˚ sweep toward the southwest brings us to the small (4′) 11th-magnitude barred spiral galaxy NGC 6951 also in Cepheus. This overlooked extragalactic wonder was discovered by American astronomer Lewis Swift with a 4½-inch refractor. Images show it as seen through galactic cirrus, or clouds of interstellar dust.

Returning to Draco, we head to 4th-magnitude Phi Draconis and look about 2¾˚ northeast for the 10th-magnitude Lost-in-Space Galaxy (NGC 6503). German astronomer Arthur von Auwers discovered this 6′-long dwarf spiral with a 2.6-inch refractor. Seen only 16˚ from edge-on, it somewhat resembles a glowing meteor train.

We end our tour just 4˚ south and slightly east of NGC 6503 at one of the sky’s finest planetary nebulae: the 8th-magnitude Cat’s Eye Nebula (NGC 6543). Lying just 3′ east of an 8th-magnitude star, this sizable 23″-wide nebula shines with a pale green color even at low power. High powers will separate well its sharp 11th-magnitude central star from its luminous inner ring. A tenuous outer shell of nebulous matter surrounds these features, giving the planetary a slightly elongated appearance.

I hope you enjoyed exploring the Golden Triangle. The objects we reviewed are but a sampling of the wonders in the region. But, as with any journey, it’s always best to leave some things unseen for when we next return.