In the premier issue of Astronomy, dated August 1973, a page labeled “Wanted: Contributors to Astronomy” put this call out to imagers: “Photographs, preferably in color whenever possible, but black and white are acceptable. For color, transparencies are preferred over prints, made with as large a film print as possible. We would like to receive 4×5 transparencies, but accept 5mm. Black and white prints should be on glossy paper, 5×7 inches or larger. Photos are used with accompanying articles, singly in special ‘Star Gallery’ photo spreads and to illustrate articles by other authors.”

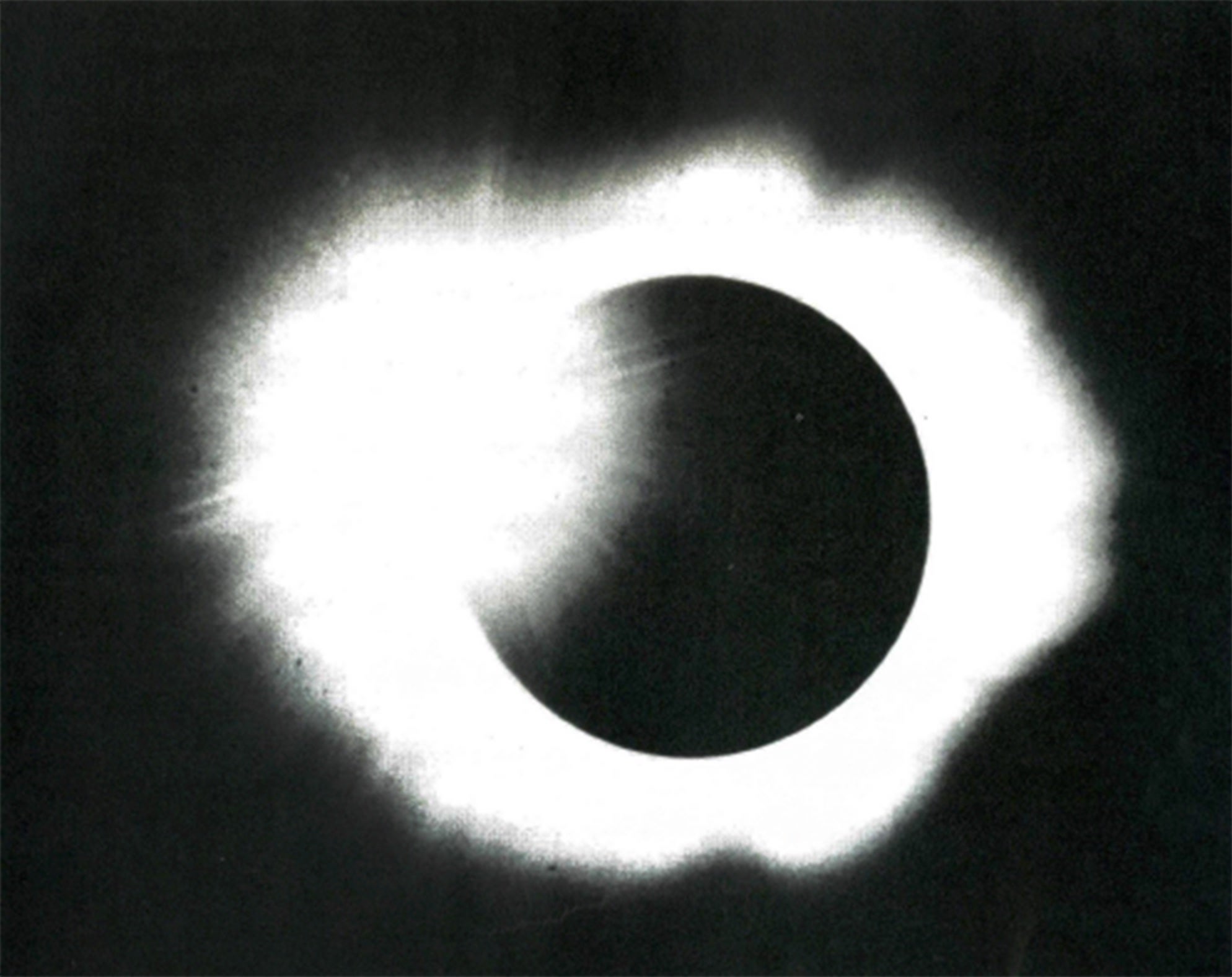

Let’s be honest. Nobody in the ’70s was taking great shots of celestial objects. Even the professional observatories were producing images that today would be considered substandard.

I used to purchase slides of deep-sky objects from Palomar Observatory in California to augment the simple talks I was giving at the time. They were created from glass plates attached to the 200-inch Hale Reflector. Many of them required multihour exposures over several nights. And all resulted in black-and-white images.

Capture it on film

The state of amateur astroimaging in early 1975 was still bad enough that, in a story titled “Piggyback Astrophotography” by Leo C. Henzl Jr., only two images accompanied the text — and both were of equipment! Indeed, backyard photographers were trying lots of new techniques to get the most out of their equipment and photographic emulsions.

As late as the November 1993 issue, Lumicon was still selling gas hypersensitization kits to improve film astrophotography. Such a technique stabilized photographic emulsions against a problem called “reciprocity failure,” where the sensitivity of the film would fall off dramatically as the exposure time increased.

The next issue saw the first true ad for a CCD camera, produced by Sirius Instruments of Villa Park, Illinois. The first story about CCD imaging appeared in March 1994. Titled “Virtual Sky,” by then-Editor Robert Burnham, the author wondered in the story’s subtitle, “If it comes at you out of a computer screen instead of an eyepiece, is it still astronomy?”

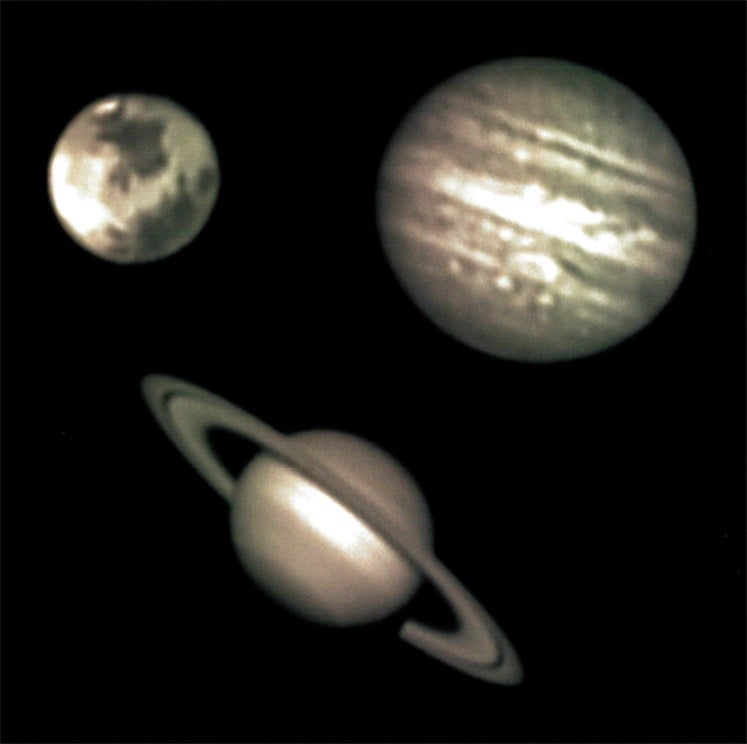

The next story about the benefits of CCD cameras was “Catching Comets with a CCD,” by Glenn Gombert and John Chumack. It appeared in the February 1995 issue. And — oh, my! — the images that accompanied the story were so miserable compared with what’s being produced today that they’re laughable. (See the images in the middle of page 56, and tell me you don’t agree.)

For the October 1996 issue, astrophotographer Tony Hallas wrote “Kodak’s Hot New Astrophoto Film.” In it he described his testing of Kodak Pro Gold 400 (also known as PPF) film. Accompanying his story were some impressive deep-sky shots — well, impressive for the time.

Then, for March 1997, Chris Schur wrote “Choosing the Right Film for Hale-Bopp,” which debuted a few images of the previous bright comet, C/1996 B2 (Hyakutake). It seemed the top imagers weren’t quite ready to make the jump to digital imaging.

The digital age

Astronomy announced two Santa Barbara Instrument Group (SBIG) CCD cameras in the April 1998 issue. Each sported a new advancement: an additional chip that made the cameras self-guiding. This was a huge moment for imagers. No longer would they have to sit with their eye glued to the eyepiece of a guide telescope, correcting for inconsistencies in the drive with tiny movements of the scope’s motors. In the September 1999 issue, a simple adaptive optics accessory, SBIG’s AO-7, promised relief from the curse of atmospheric seeing.

The first roundup and recommendations of CCD cameras appeared in the February 2000 issue. The story, “Capture the Sky on a CCD” by Gregory Terrance, was the first of a three-part series on CCD imaging. And, like most amateur efforts during that time, the pictures that appeared with the stories would be tossed out by today’s imagers.

When I became photo editor in 2003, the magazine was still receiving slides and photographs in a rough 3-to-1 ratio. To use them in the publication, I had to send each out to a photographic service company for scanning. Amateurs didn’t start sending digital images until 005, and those were all on CD-ROM disks. Things are so much simpler now.

A picturesque future

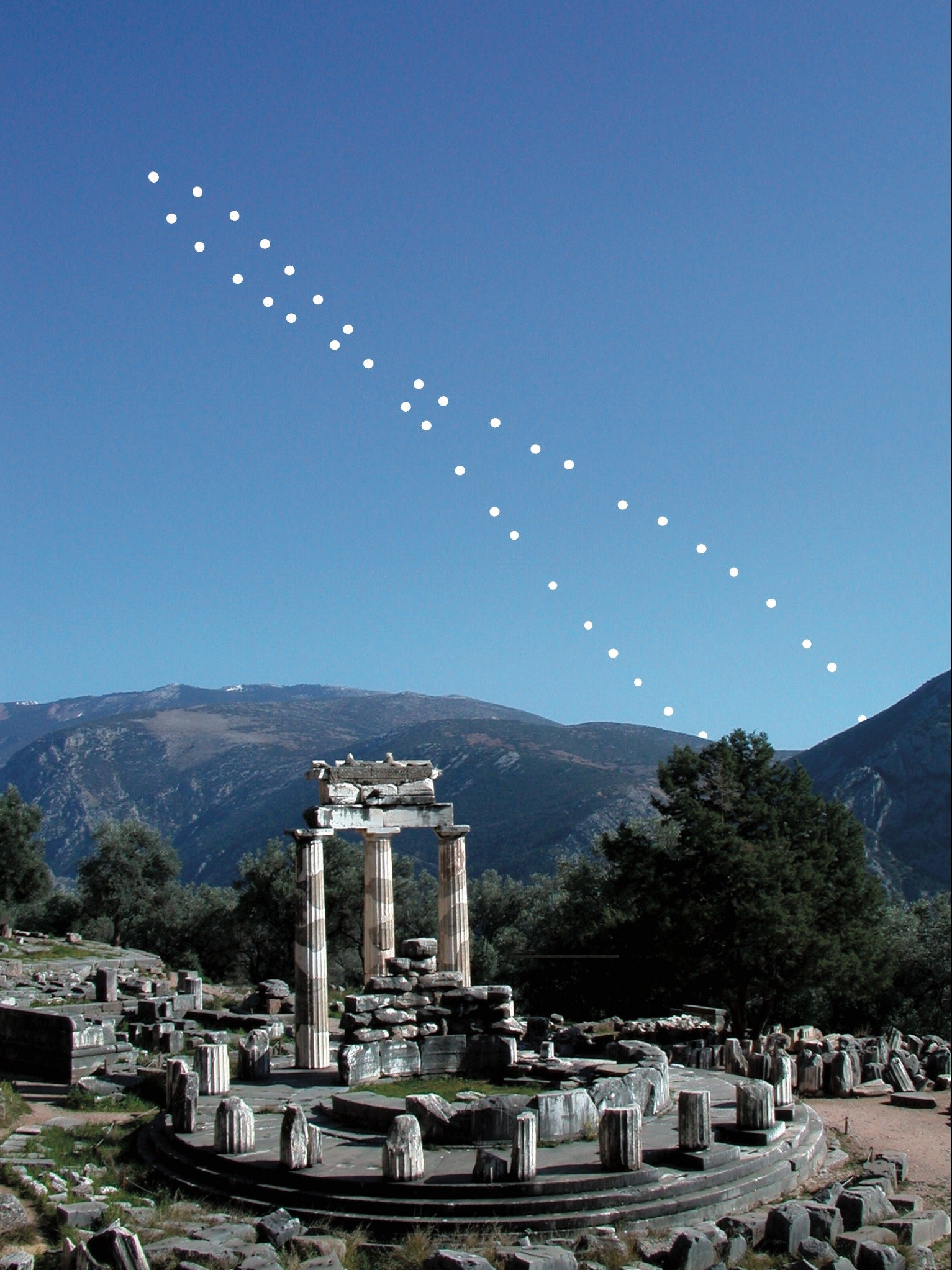

Today’s astroimagers benefit from a half-century of improvements in optics, drives and mounts, cameras, and software. We owe our thanks to lots of inventors and manufacturers who were willing to take a chance. Also, let’s not forget the hundreds of thousands of examples of trial and error by dedicated amateur astronomers that brought us to where we are now.

Hopefully, history will repeat itself so that when I write “100 years of astroimaging” in the August 2073 issue, we’ll all look back and chuckle at the “poor” state of early 21st-century imaging. Until then, keep shooting!