In the pioneering days of long-exposure astrophotography in the late 19th century, the use of dry plates over wet collodion plates simplified the photographic process. The increased light sensitivity of the emulsion coatings on dry plates allowed for shorter exposure times and produced sharper images of the night sky. In 1881, the French inventors brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière made improvements to these plates, rendering them easier and more convenient to use.

The results led to a new wave of scientific inquiries, and brought to light many features that weren’t obvious to the eye. One such feature in Cygnus likely appears in many images taken by modern astrophotographers with basic equipment, though few may have noticed it.

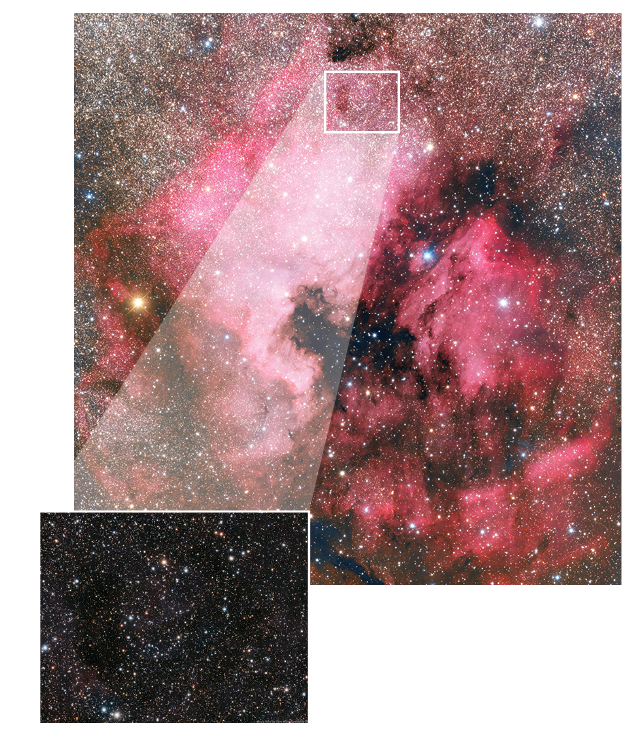

In 1910, American astronomer Daniel Walter Morehouse used a Sigma Lumière dry plate to make a long exposure of the North America Nebula (NGC 7000) — the central figure of a region “most remarkable,” he wrote, for its variety of bright and dark nebulae. When Morehouse was developing the plate, “a number of curious spots appeared.” This was no surprise, as such features were characteristic to this brand of plate. However, a prominent dark ring appearing “a little to the north of the ‘St. Lawrence River’ region” — treating the North America Nebula as a map of its namesake — attracted his attention. Morehouse described it as “a ring formed by the absence of stars.” A second photograph at that time verified the structure’s existence, although, he said, it was not as conspicuous.

Not until 1926, however — when Morehouse was president of Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa — did he return to observing the object. That summer, he saw the dark ring standing out “with tantalizing clearness” in a 9¾-hour exposure taken over the course of two nights by Theodore G. Mehlin and Richard S. Zug with Drake Observatory’s 8.25-inch refractor, newly equipped with a Brashear photographic doublet. “A careful examination of the negative,” Morehouse said, “convinced me that the structure is a ring of black nebula … [that] forcibly reminds one of the Ring Nebula in Lyra except that it is much larger.”

The following year, he published his findings in the February issue of Popular Astronomy, in which he postulated that this feature is caused by a ring of black absorbing material that appeared to be in abundance throughout this portion of the Milky Way.

In June 1927, Morehouse and Zug took an additional 6½-hour exposure at Drake Observatory. They used the image to count the stars in the ring and its immediate vicinity. Their results, published in the 1928 Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, confirmed the existence of a dark, absorbing nebula that appeared to lie some 1,500 light-years distant. However, they did not toss out the possibility that the ring could be composed of two nebulae at different distances.

After Edward Fath, director of Goodsell Observatory at Carelton College in Northfield, Minnesota, studied the ring on numerous photographs, he wrote to Morehouse in a private correspondence saying, “It is certainly a very peculiar structure in that it is so nearly circular,” and, like Morehouse, wondered if it was a dark Ring Nebula.

You’ll find Morehouse’s dark ring at R.A. 20h56m, Dec. 45°31′, measuring 30′ by 12′ across. For several years prior to imaging this dark ring, Morehouse had referred to the structure as “The Bird’s Nest.” In 1927, Edward Emerson Barnard cataloged the dense eastern segment as dark nebula 353 (B353). In the ring’s hollow region, toward its southern end, lies NGC 6996. It is currently uncertain whether this star group is an actual open cluster. However, recent data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission — as well as the ground-based 2MASS survey and other independent studies — have found associated members.

While this fascinating and puzzling dark ring is easily captured in images, I’m wondering what it takes to see the complete ring visually, not just the dense eastern portion that comprises B353. I would hazard a guess that low-power views will be best, as it will condense the fainter segments of the ring, making it more apparent. As always, be sure to send reports on what you see or don’t see to sjomeara31@gmail.com