Lucky is the word I’d use for any telescopic observers who got to see one of the most stunning spectacles in nature when Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 impacted Jupiter in July 1994. The collision left inky scars in the planet’s atmosphere that persisted for months, with the largest welts visible in even the smallest of telescopes.

While at the time, witnessing an impact on another world seemed like a once-in-a-lifetime event, amateur astronomers and space scientists alike have continued to record other, albeit much smaller, impacts on Jupiter. About a dozen such events are known to date; undoubtedly that number will continue to rise.

In a 2018 Astronomy & Astrophysics paper titled “Small impacts on the giant planet Jupiter,” Ricardo Hueso and colleagues estimated that small objects about 16 to 65 feet (5 to 20 meters) or larger should impact Jupiter and be observable from Earth once every 0.4 to 2.6 years. Most of these events have been captured as flashes without any discernible scarring — but larger events have occurred.

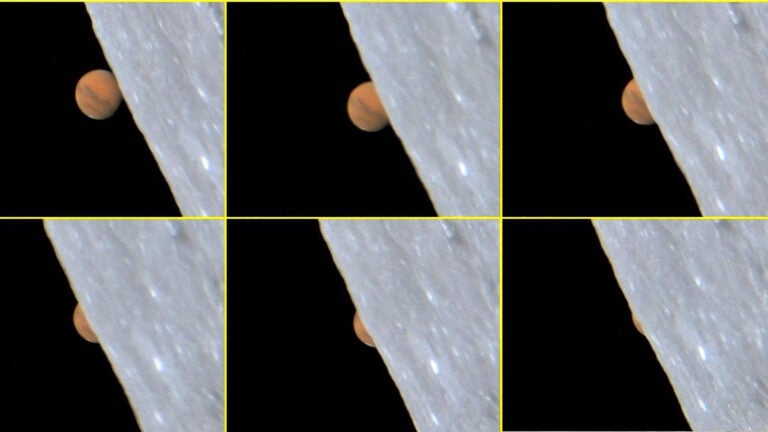

Most notable was the July 19, 2009, dark impact scar discovered by Australian amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley. In images taken with his 14.5-inch reflector, the impactor (approximately 650 to 1,600 feet [200 to 490 m] in diameter) left a 5,000-mile-long (8,000 kilometers) dark scar in Jupiter’s southern hemisphere.

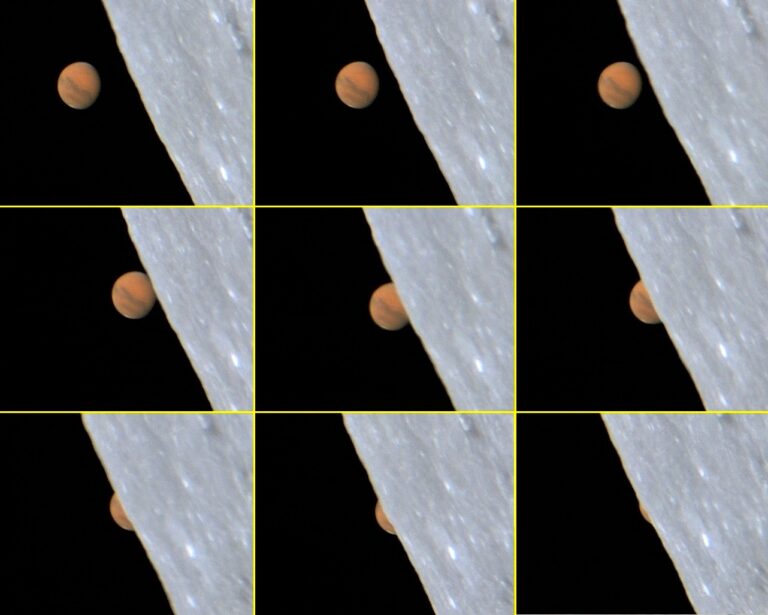

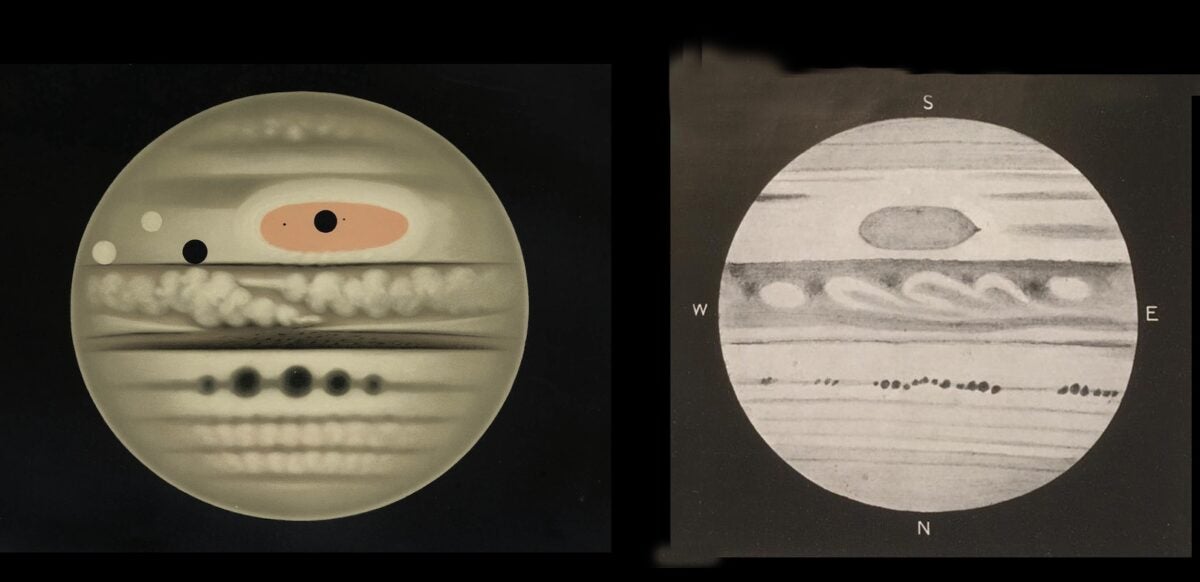

In April 2024, Pawel Drozdzal, a Ph.D. student at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poland, alerted me to a paper published Feb. 1, 1997, in Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. In “Discovery of a possible impact spot on Jupiter recorded in 1690,” lead author Isshi Tabe and colleagues reported their discovery of a dark spot drawn by Italian astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini in December 1690. They stated that the spot was similar to those produced by Comet D/Shoemaker-Levy 9’s impact. Over a period of 18 days, Cassini observed and sketched this spot as it was stretched out by Jupiter’s zonal winds into a series of wispy trails. Taking this series of drawings as circumstantial evidence — and using a simple simulation to confirm their suspicions — the authors concluded that the spot was “possibly produced by the impact of a single astronomical object around 1690 December 5.”

Another eyebrow-raising Jupiter drawing was created on Nov. 1, 1880, by French astronomical artist Étienne Léopold Trouvelot, recording five large black spots on the planet’s North Temperate Belt (NTB). He described the view in his 1882 book The Trouvelot Astronomical Drawing Manual, noting that in October 1880, a relatively calm four-year period on Jupiter ended “when considerable commotion occurred on the northern hemisphere.” He also stated that when the spots first appeared, they “had some resemblance to Sun-spots without a penumbra, with bright markings around them, resembling faculae. These round spots subsequently enlarged considerably, until they united along the entire line, encircling the planet, and finally forming a narrow pink belt…”

In his classic 1958 work The Planet Jupiter, British astronomer Bertrand Peek wrote that this occurrence was the first time in recorded history that an outbreak of dark spots had been seen at the south edge of the NTB. The spots also displayed the shortest rotation periods that had ever been observed on Jupiter. Planetary scientists now know this region has the fastest zonal jet on Jupiter.

The renowned British observer William F. Denning also observed the NTB dark spots, first recording them on Oct. 23, 1880. By the end of October and early November, he tried to identify them at succeeding transits across the planet’s central meridian but “found such considerable changes in their appearance and distribution that only the two principal spots could be followed,” he reported in The Observatory. Indeed, compared to the five substantially large spots that Trouvelot drew, a later drawing by Denning on Nov. 29, 1880, shows how the spots had evolved into a long train of tiny spots.

While these statements are remarkably reminiscent of the SL-9 impact scars, transforming into a smoky red band as they dispersed, scientists don’t have any direct evidence of an impactor. One could postulate that impacting objects may have triggered the creation of this disturbance, as observers had never seen dark spots at that location on the planet before, but there is no evidence.

I hope you continue to observe Jupiter, as one never knows when a comet or asteroid will strike. As always, send thoughts to sjomeara31@gmail.com