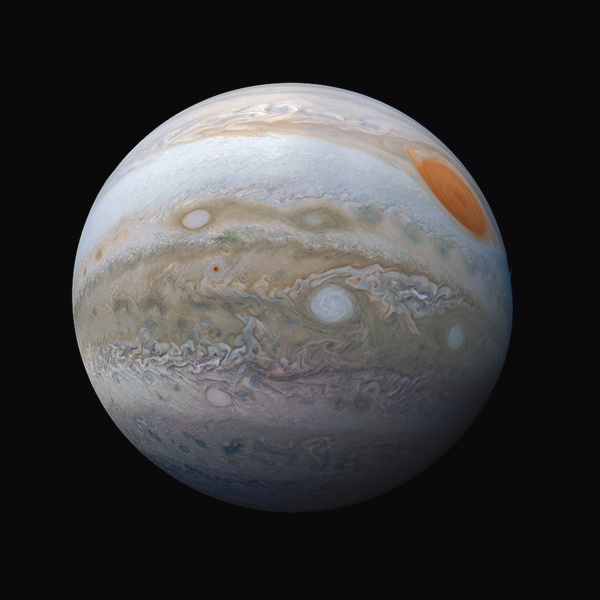

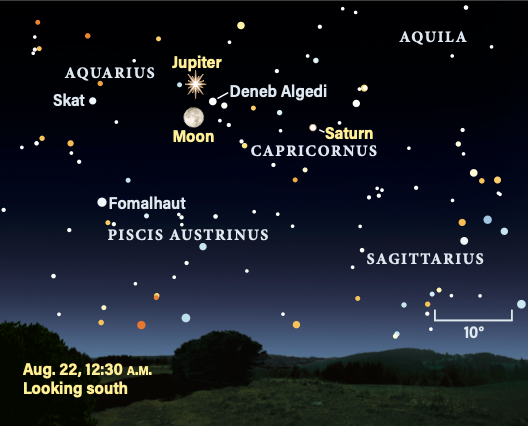

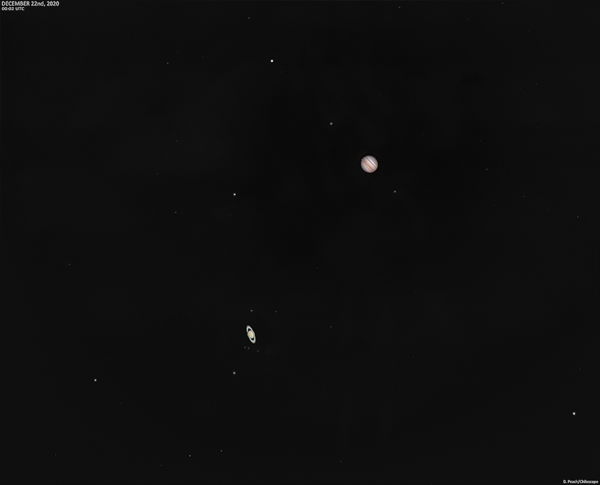

At opposition, Jupiter will shine at magnitude –2.9. It will be 373 million miles (600 million kilometers) from Earth and it will appear 49″ in diameter, which is only 1″ less than its maximum size. Fortunately, catching the exact moment of opposition isn’t critical, as the view will be essentially the same for roughly 10 days on either side of the event itself. This offers observers ample time to seek out the gas giant’s most intimate details. And from shredding cyclonic masses to spotted tropical storms, Jupiter’s ever-changing cloud tops never fail to reward.

As seen from mid-northern latitudes, Jupiter will culminate, or reach its highest point in the sky, around 1 a.m. local time, when it climbs nearly 36° above the southern horizon. Two nights after opposition, the bright planet passes nearly 5° due north of the Full Moon. Although the Moon’s bright light is a detriment to deep-sky observing, it will not hinder observations of Jupiter. In fact, it will help by reducing glare, which creates a more pleasant view of the planet. This night could be an optimal time for you to seek out something special. The question is, what should you look for?

An awe-inspiring world

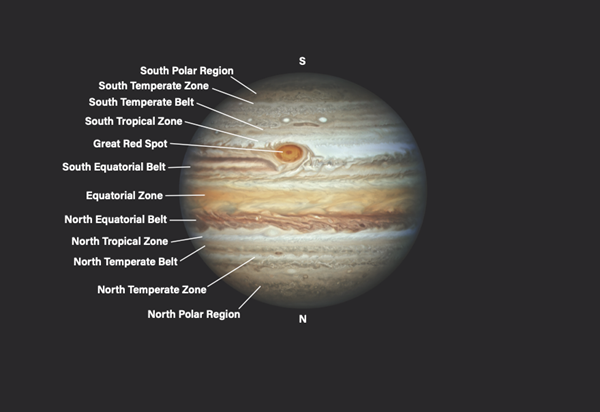

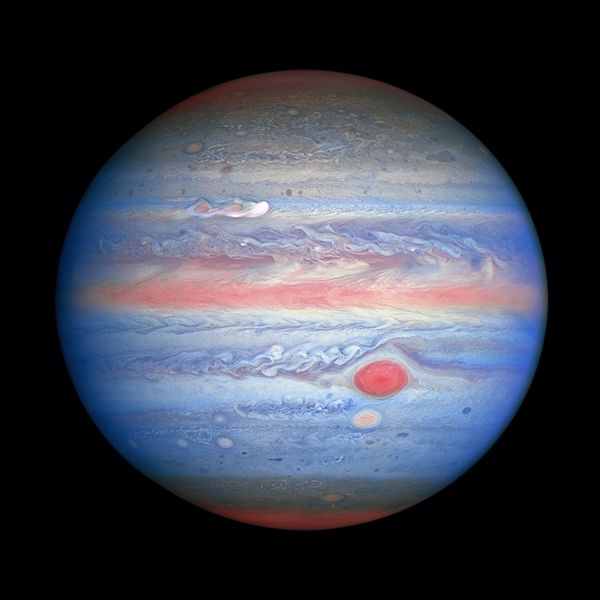

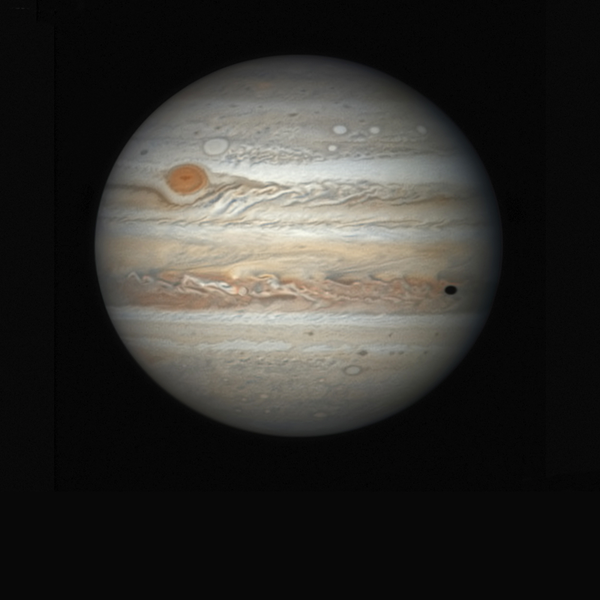

At a glance, Jupiter’s entire face is covered with reddish brown belts and bright zones of various hues, all of which run parallel to the planet’s equator. Careful observations during the most pristine moments of steady atmospheric seeing, however, reveal even finer details. These include bright and dark spots, looping festoons, and other shapes that, despite their solid appearance, are in a state of perpetual change. Such shapeshifting is a result of powerful jet streams whipping both west to east (prograde; in the direction of rotation) and east to west (retrograde; opposite the direction of rotation) across the planet.

These jets separate Jupiter’s bands, and the instabilities they introduce can spur atmospheric waves and cyclonic storms, as well as eruptive plumes that distort the flow and color of the planet’s zones. Trying to predict when such events might occur is a bit like forecasting storms on Earth, where one analyzes historical and current trends to attempt to presage future activity.

So, let’s start by exploring some past events on Jupiter to see if they’ll tell us anything about the future. What follows is based, in part, on information gleaned from reports by Glen Orton and Thomas Momary of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and John Rogers of the British Astronomical Association. Remember, though, that Jupiter is a dynamic world and it’s always ready to surprise.

The Great Red Spot

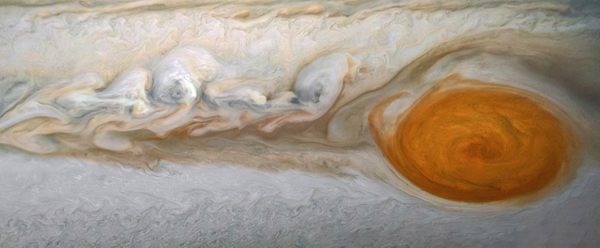

The mystifying colossus that is the Great Red Spot (GRS) is the largest and most enduring storm in the solar system. And since 2017, the development of particularly intense color within the storm (the likes of which hasn’t been seen for decades) has captivated observers — alongside its slivers of red flakes, blades, and hooks spinning off the Spot like ice skaters playing Crack the Whip. Some of these events were obvious enough to be spied through a 3-inch refractor at 300x. Given that the GRS had been shrinking in size at an accelerated rate since 2012, concerns arose that the flaking episodes signaled its demise was near.

These flaking events could continue through opposition, too. Either way, you might want to time your Jupiter observing sessions to track the Spot’s passage across the planet’s meridian, monitoring whether the storm’s apparent size grows or shrinks over time. Also pay attention to the GRS’s color, which has shown signs of fading recently.

The Little Red Spot

Observers should also keep an eye out for Jupiter’s long-enduring Oval BA, which formed in 2000 in the planet’s South Temperate Belt through the collision and merger of three smaller spots. Oval BA started off as white. But it began to redden in late 2005, leading to the catchy moniker the Little Red Spot (or Red Spot Jr.).

Then, in 2018, Oval BA’s reddish hue started disappearing, ultimately returning the storm to a brilliant white color in 2019. By late 2020, however, the oval’s core began to redden again. Astronomers believe atmospheric warming events are responsible for shifting the spot’s color from white to red. So, if the region continues to warm, we might be treated to a revived Little Red Spot during this year’s opposition.

Clyde’s Spot

Early in the morning on May 31, 2020, amateur astronomer Clyde Foster of Centurion, South Africa, imaged a curious new spot that had formed in Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. He did so using a filter sensitive to certain wavelengths of light that are absorbed by methane gas, which is prevalent in Jupiter’s atmosphere. The spot, however, was not visible in other images captured just hours earlier by astronomers based in Australia.

Only two days later, though, the Juno spacecraft snapped an image of what was quickly dubbed Clyde’s Spot, a feature that turned out to be a plume of material erupting above the upper cloud layers of Jupiter’s colorful atmosphere.

During this year’s opposition, make sure to keep your eyes peeled for new eruptions, which occasionally occur around this latitude.

Equatorial Region

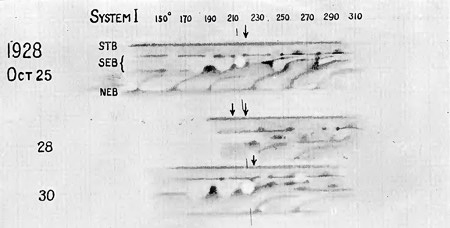

Jupiter’s dark bands are known to expand, contract, or whiten for many months at a time. And occasionally, they fade away entirely. For example, in February 2020, a white storm erupted in the gas giant’s South Equatorial Belt (SEB), ultimately spreading through the region to create a brighter zone that remains as of early 2021. However, it’s hard to know what will happen in the area during this opposition.

The most dramatic event would be an SEB revival, where eruptions of bright white plumes signal a return to the SEB’s standard brown appearance. SEB fade-and-return cycles can occur at intervals ranging from about three to 15 years. But then again, droughts between cycles can last as long as 36 years, with many intervening years of normal SEB activity. During this opposition, look for a possible color shift in the bright SEB zone, which has shown signs of yellowing in early 2021.

Every three to five years, Jupiter’s North Equatorial Belt (NEB) expands to both the north and south. This expansion is associated with the dramatic and chaotic mixing of bright and dark material. After such an event occurred in 2017, the NEB ballooned again, as predicted, in May 2020.

First, a bright rift developed in the northern part of the NEB. It soon ejected dark material to both the north and south — perhaps as gas from the bright, ammonia-depleted plumes fell back into the deeper (and darker) jovian atmosphere. Shortly after this activity, new dark elliptical features called barges, as well as white ovals, developed. While this action appears to be on the wane, it’s unknown whether renewed activity might follow.

Aspects of the EZ disturbance have continued into early 2021, though. Namely, the EZ’s northern section remains smoggy. Meanwhile, its southern section has brightened. Scientists are now interested in any changes to the EZ’s color, whether it returns to its normal brightness or experiences a renewed darkening that might presage a truly disruptive event.

Strip Sketches

Without question, today’s amateur astrophotographers can snap outstanding images of Jupiter that almost rival those taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. These photos are of immense scientific value and their creators should be applauded. In mere moments, they can capture planetwide details that are impossible for visual astronomers to reproduce by hand, given the gas giant’s fast rotation.

But visual astronomers can also record fantastic details on Jupiter by creating a strip sketch. This technique focuses on just one small section of the planet, allowing the observer to record as much detail as possible over the course of, say, 30 minutes to an hour or more. The method allows the sketcher to take advantage of crisp moments of perfect atmospheric seeing to record sub-arcsecond details in a small region of interest. It also allows them to track changes in that region over time, such as the rotation of the Great Red Spot, the movements of bright and dark features within a disturbance, or, as the illustration above shows, a revival of the South Equatorial Belt.

Just remember, make the sketches large so you don’t limit the space between features, which are difficult to render at a smaller scale. For telescopes with apertures of 6 inches and smaller, a general magnification of 200x to 250x is sufficient. But if Earth’s atmosphere is outstandingly steady, you can try pushing that limit to 75x per inch of aperture. Even if you make as few as four strip sketches of the same region during each apparition, you will create a general record of the changing aspects of this dynamic world. — S.J.O.

Northern tropical regions

On Aug. 18, 2020, a spectacular eruption occurred in Jupiter’s North Tropical Belt (NTB) jet stream, producing an elaborate wake. Scientists had forecast that the eruption would occur in 2021, but it went off a year early. As the storm stretched out over time, amateurs discovered two more storms at the same latitude. All of them were superfast plumes with turbulent wakes that disrupted the entire width of the North Tropical Zone (NTZ), as well as the southern edge of the NTB.

While it’s common for storms to pop up in this region every six years or so — often, multiple storms rage — it’s unknown whether more events will continue to materialize during this year’s opposition. While the individual plumes themselves are short-lived, color changes within the zone usually follow. And observations in early 2021 revealed that the NTZ has indeed become smoggy, mimicking the color of the northern EZ.

Galilean satellites

Several mutual events, such as occultations and eclipses, of Jupiter’s satellites are visible during August. And three of them occur near opposition, when the planet and its Galilean moons look largest, offering you the best opportunity to study the satellites in detail. While most events require modest or large telescopes and high magnifications to see well, small telescope users can witness some of the events — especially partial occultations and the dimming or brightening effects present during greatest eclipses or pairings, respectively. To find out which mutual events are visible from your location in August, visit http://nsdb.imcce.fr/multisat/nsszph517he.htm and enter the code for the observatory nearest you from the available list.

Considering all the exciting possibilities for dramatic jovian events, August’s opposition may prove to be one of the most memorable in recent years. The examples given here are but a few of the many potential sights that you might see at any time during Jupiter’s apparition. Plus, who knows: Your amateur observations might even be key to helping professionals unlock the mysteries of this fascinating world.

Good luck, and may the wonders of Jupiter delight you!