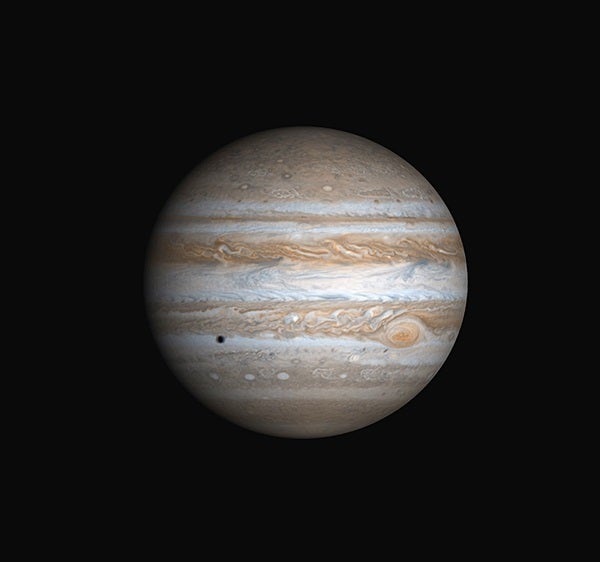

Jupiter’s dynamic atmosphere displays a wealth of detail through telescopes of all sizes, particularly in the weeks surrounding its early April opposition.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

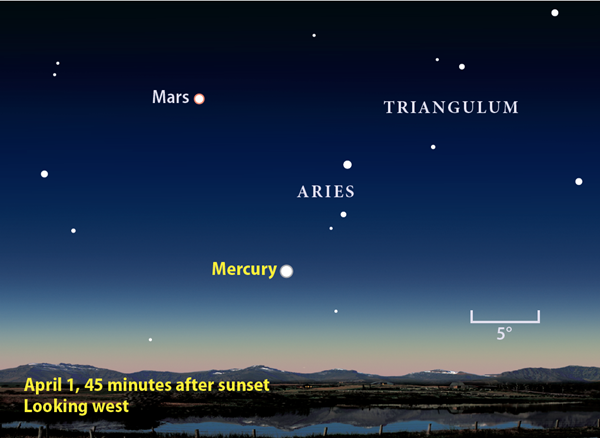

Mercury, Mars, and the Moon will delight evening observers in early April. The three create a fine prelude for the month’s “star” performer, Jupiter. The solar system’s largest planet reaches peak visibility in April and remains visible throughout the night. As Jupiter dips low in the west before dawn, early risers can enjoy nice views of ringed Saturn in the south while brilliant Venus dominates the east.

Although Mercury has a reputation for being hard to see, novices who head out in evening twilight April 1 might wonder why. The innermost planet stands 12° high in the west a half-hour after sunset and dips to a still-respectable 7° high 30 minutes later. Mercury shines at magnitude –0.1 and shows up easily against the fading twilight. Meanwhile, fainter Mars appears 15° to its upper left and the waxing crescent Moon gleams some 30° to the Red Planet’s upper left.

April 1 marks the peak of Mercury’s best evening appearance of 2017. Point a telescope at the planet and you’ll see its 8″-diameter disk and 39-percent-lit phase. A week later, Mercury appears 9″ across and the Sun illuminates just 16 percent of its Earth-facing hemisphere. Unfortunately, the planet has dimmed to magnitude 1.6 and hangs lower in the twilight sky. The Sun’s glare swallows the fading world just a few days later.

Mars glows at magnitude 1.5 for most of April. It’s a conspicuous point of light above the western horizon as darkness falls and doesn’t set until shortly after 10 p.m. local daylight time. A telescope won’t help you enjoy the ruddy world — even the best instruments show only a featureless disk 4″ across. Instead, Mars shines this month by the company it keeps.

The Red Planet moves from Aries into Taurus on April 12, setting up a string of pretty binocular conjunctions. Mars passes less than 4° south of the Pleiades star cluster (M45) on the 19th and 20th, but the pair appears in a single field of view for more than 10 days. And during the month’s final week, the planet stands between the Pleiades and Hyades clusters.

A waxing crescent Moon punctuates this scene April 27 and 28. On the 27th, the slender crescent lies 9° south of the Pleiades and 11° west of 1st-magnitude Aldebaran, the luminary that marks one tip of the V-shaped Hyades. The following evening, a slightly fatter crescent Moon stands 4° east of Aldebaran. With Mars entrenched between the two clusters, the star-studded gathering creates a stunning scene in the deepening twilight.

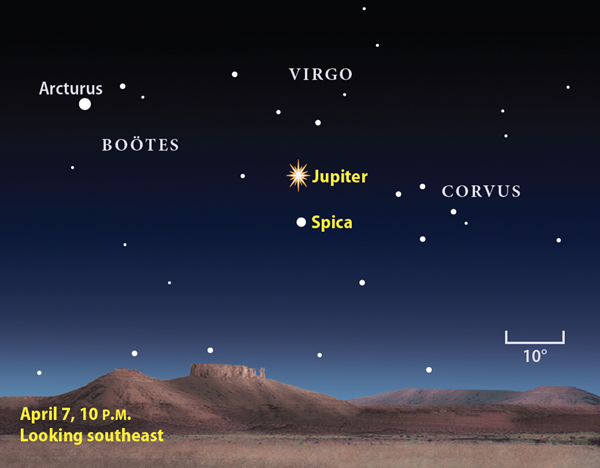

The solar system’s biggest planet lies in Virgo at its April 7 peak, not far from that constellation’s brightest star, Spica.

Astronomy: Roen Kelly

If you shift your gaze from west to east as darkness falls, Jupiter immediately grabs your attention. The giant planet reaches opposition April 7, when it lies opposite the Sun in our sky and thus stays on view all night. Opposition also brings the planet closest to Earth, so it shines brightest and appears largest through a telescope.

You won’t mistake Jupiter for any other object. Blazing at magnitude –2.5, it shines 25 times brighter than Spica, the 1st-magnitude luminary of its host constellation, Virgo. The gap between planet and star grows from 6° to 9° as Jupiter moves westward during April. The giant world has a closer encounter when it slides 10′ south of 4th-magnitude Theta (θ) Virginis on April 5.

Jupiter pulls within 414 million miles of Earth at opposition. The gas giant thus looms large and shows dramatic detail when viewed through a telescope. Great views come when it’s higher as midnight approaches.

At opposition, Jupiter spans 44.3″ across its equator. If you look carefully, you’ll notice that its polar diameter comes up short, measuring just 41.4″. This polar flattening — obvious even through small scopes once you know to look for it — arises from Jupiter’s gaseous nature and rapid spin.

The top of Jupiter’s atmosphere breaks into a series of bright zones and darker belts. Two belts stand out in particular, one of either side of a zone that coincides with the planet’s equator. During moments of good seeing, you’ll likely see several more belts and zones. Also keep an eye out for the Great Red Spot. If you don’t see it on first look, wait a few hours for the planet’s spin to bring it into view.

While you relish watching Jupiter’s dynamic atmosphere, don’t forget that NASA’s Juno spacecraft enjoys a better view from orbit. The probe concentrates on the planet’s polar regions, with the JunoCam instrument taking images during each close pass. You can follow the mission’s progress at missionjuno.swri.edu.

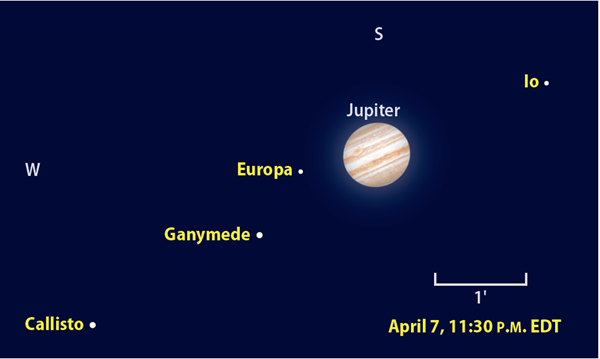

Four bright satellites string out east and west of the giant planet on the night it reaches opposition and peak visibility.

Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Equally captivating are Jupiter’s four big moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of distance from the gas giant. The satellites spend most of their time either east or west of the planet, but each of the three inner ones passes in front of the jovian disk once an orbit. During such a transit, the moon also casts its shadow onto the planet’s bright cloud tops, where it appears as a distinct black dot. Half an orbit later, the moon passes behind Jupiter (an occultation) and disappears in the planet’s shadow (an eclipse).

Although satellite events occur every day, some appeal more than others. Here we highlight several of the best for North American observers. Io transits Jupiter on the evening of April 2. The Moon’s shadow touches the planet’s disk at 11:31 p.m. EDT followed eight minutes later by Io itself. The moon seems to hover just east of the shadow throughout the transits. This is a sign that the Sun lies almost directly behind Earth, as it will at opposition on the 7th.

Compare these transits to the ones the night of April 9/10. In the latter case, Io first appears against Jupiter’s cloud tops at 1:22 a.m. EDT followed by the shadow three minutes later. The moon now leads its shadow as they cross the planet’s disk.

On the night of opposition, April 7/8, Jupiter’s shadow falls directly behind the planet. Although all four moons show up in the evening, Europa passes behind the planet from 1:36 to 4:04 a.m. EDT. In a rare circumstance that can happen only at opposition, Jupiter simultaneously occults and eclipses the moon. A day later, on April 9, Io emerges from behind the planet’s eastern limb at 6:15 a.m. EDT, but you won’t see it until it emerges from Jupiter’s shadow three minutes later.

On the evening of April 14, watch Europa and Callisto approach Jupiter almost in lockstep. After midnight, Europa passes behind Jupiter’s limb at 3:52 a.m. EDT and emerges from the planet’s shadow at 6:38 a.m. (after the planet sets from eastern North America). Meanwhile, outermost Callisto passes above the planet’s south pole.

Saturn rises near 1:30 a.m. local daylight time at the start of April and some 30 minutes earlier with each passing week. The magnitude 0.3 ringed planet lies against the Milky Way star fields of northwestern Sagittarius. It moves slowly eastward during the month’s first few days, then reaches a stationary point on the 6th before starting a westward trek.

The inner world appears at its best for the year in early April, when it shines brightly and displays a pretty crescent disk through amateur scopes.

Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Although binoculars won’t reveal details on Saturn, they will show the delightful backdrop. Throughout April, the planet lies within 4° of the open star clusters M21 and M23 as well as the spectacular Lagoon (M8) and Trifid (M20) nebulae.

The best views of Saturn through a telescope come when it climbs highest in the south near the start of twilight. The planet’s disk measures 17″ across at midmonth while the ring system spans 39″ and tips 26° to our line of sight. The large tilt lets you see exquisite ring detail. First, take in the Cassini Division — the dark gap between the outer A ring and the brighter B ring. You should be able to see Saturn’s disk through this opening. Next, notice the outer edge of the A ring poking above the planet’s north pole. Finally, look for Saturn’s shadow on the backside of the rings just off the planet’s western limb.

Like Jupiter, Saturn has a family of moons, though only 8th-magnitude Titan is bright enough to see through all telescopes. Look for it north of Saturn on April 6 and 22 and south of the planet April 13 and 29. Three 10th-magnitude moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — orbit inside Titan and show up through 4-inch and larger scopes. The quick pace of these inner three satellites means they often change positions noticeably over the course of an hour or two.

The approach of dawn brings the brightest planet into view. On April 1, Venus rises an hour before the Sun and climbs 5° above the eastern horizon 30 minutes later. By month’s end, it pops above the horizon 100 minutes before sunup and stands 13° high a half-hour before sunrise. The planet brightens considerably in April as well, from magnitude –4.2 on the 1st to its maximum of magnitude –4.7 on the 30th.

Observers who target Venus through a telescope in April will see it undergo striking changes. On the 1st, the planet spans 58″ and shows a dramatic, 3-percent-lit crescent. By the 30th, the planet’s diameter has dwindled to 38″ while the crescent has fattened to 26 percent illumination.

The solar system’s ice giant planets fare poorly in April. Uranus remains lost in the Sun’s glare all month. Neptune briefly returns to view at month’s end, but it lies only 5° high in the east as morning twilight begins. You’ll be hard-pressed to see the 8th-magnitude planet so close to the horizon.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS | ||

| Evening Sky | Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (west) | Jupiter (south) | Venus (east) |

| Mars (west) | Jupiter (west) | |

| Jupiter (southeast) | Saturn (south) | |

| Neptune (east) |

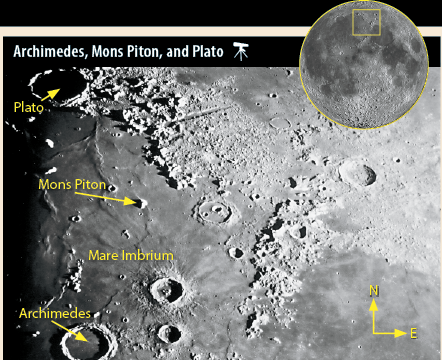

The eastern edge of Mare Imbrium features giant craters and isolated mountain peaks.

Consolidated Lunar Atlas/UA/LPL;inset: NASA/GSFC/ASU

On the shoals of a rainy sea

Chances are pretty good that your first memorable view of the Moon through a telescope revealed a landscape packed with dramatic craters arrayed along the dividing line between lunar day and night known as the terminator.

You can rekindle those memories on the evening of April 4, a day after First Quarter phase. Notice the perfectly circular crater Archimedes, which rests on the terminator halfway from the lunar equator to the north pole. The ragged eastern rim of this 52-mile-wide crater projects sharp shadows onto its smooth, lava-filled floor, while the western rim throws even longer spikes to the west. Galileo Galilei realized in 1610 that even the gentlest lunar hill would cast a long shadow under a low Sun angle.

To the north and a little east of Archimedes, the solitary Mons Piton rises from the wrinkled floor of Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains). The large elliptical crater Plato to its northwest appears as a broken outline early on the evening of the 4th. Watch it become whole during the next couple of hours.

Over the next few nights, the Sun gradually illuminates Mare Imbrium and reveals its true extent. No one recognized this circular feature as an enormous impact basin until the early 1960s, when planetary scientists noticed a pattern of multiple rings centered on Mare Orientale at the Moon’s western limb. Researchers quickly noticed similarities to many other large maria, and connected these features to giant impacts. Mons Piton and some other nearby isolated peaks suddenly fit into a broader picture as the tallest mountains in a ring largely submerged under lava that welled up long after the basin formed.

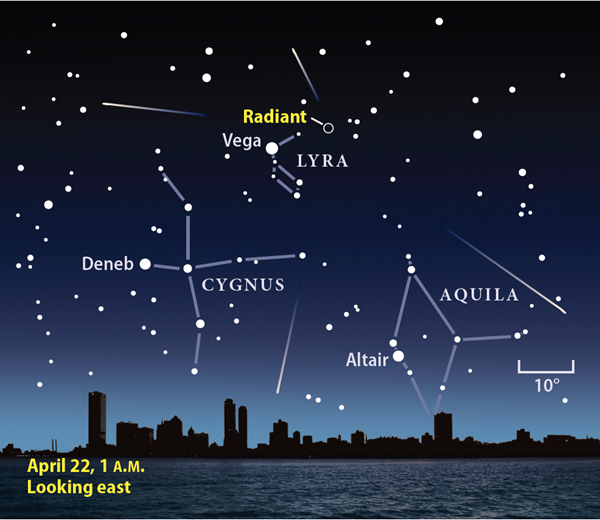

With a slim crescent Moon rising around 4 a.m. local daylight time, conditions should be great for April’s top meteor shower.

Astronomy: Roen Kelly

The Lyre plays a sweet song

Although the Lyrid meteor shower often rates as an afterthought on the calendar of annual showers, this year should be different. Peaking under a waning crescent Moon the morning of April 22, the Lyrid shower promises the best viewing conditions of any spring or summer shower this year. Observers who seek out dark skies should see up to 18 meteors per hour before dawn.

The “shooting stars” appear to radiate from the constellation Lyra the Lyre, a region that rises in late evening and climbs nearly overhead by the time twilight commences. Be sure to dress warmly to ward off the morning chill. Then, use your naked eye to scan the sky roughly 30° to 45° from the radiant.

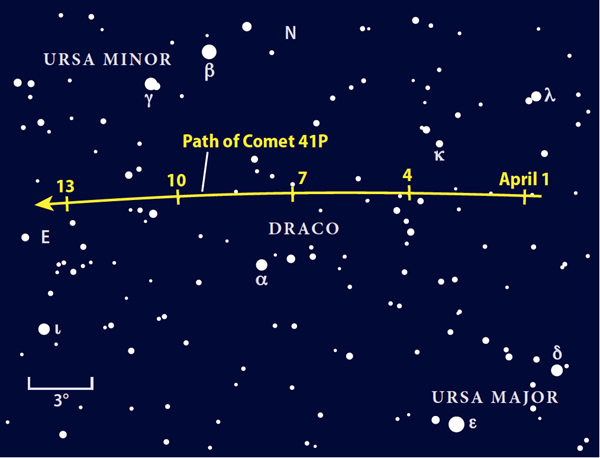

This icy visitor puts on a fine show for Northern Hemisphere observers in April when it makes its closest approach to both the Sun and Earth.

Astronomy: Roen Kelly

A bright comet’s all-night performance

It’s hard to believe that just six months ago, we had to scour the sky to find a 12th-magnitude comet. This month, we’re not featuring two 7th-magnitude objects because we have something better. Comet 41P/Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresak could reach 5th magnitude and be visible to the naked eye from dark-sky sites.

Comet 41P sails across the northern sky during April. It spends the first half of the month among the background stars of Draco, between the brighter patterns of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor. This region remains on view from dusk to dawn. The periodic visitor passes closest to Earth on April 1 and closest to the Sun on the 13th.

Remember that comets are notorious for defying brightness predictions. Conservative estimates peg 41P at 8th magnitude, which would make it a decent telescopic comet. More optimistic scenarios have it reaching as high as 5th magnitude — within the range of the naked eye from the country and binoculars from the suburbs. Those are the extremes we should plan for, but a plan C exists: In 1973, the surface of this dirty snowball cracked and gushed gas and dust for a couple of weeks, forging an outburst of 10 magnitudes. If that happens again, we could have the comet of the decade on our hands.

In early April, the best viewing comes in the moonless hours before dawn. Comet Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresak then should be near peak brightness and quite active. As the Moon moves into the morning sky toward the end of April’s second week, optimal viewing shifts to the evening sky.

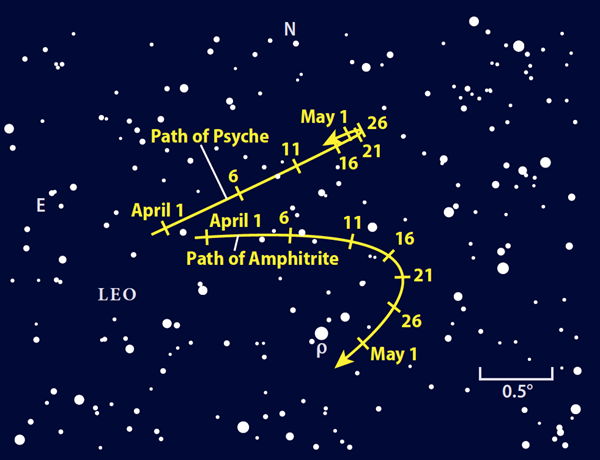

Psyche nips at the heels of Amphitrite as the two minor planets march through the background stars of southern Leo the Lion.

Astronomy: Roen Kelly

Two space rocks for the price of one

By late evening in April, you can find Leo about two-thirds of the way from the southern horizon to the zenith. The Lion’s heart, 1st-magnitude Regulus, dominates this constellation. Head 7° east-southeast from it and you’ll land on magnitude 3.8 Rho (ρ) Leonis. Asteroids 16 Psyche and 29 Amphitrite lurk near this unassuming star during April.

Amphitrite begins the month at magnitude 9.8 while Psyche glows about a magnitude fainter. To snare these minor planets from the suburbs, you’ll need a 4-inch or larger telescope. Try a magnification of about 75x to bring in the fainter background stars you see on the map below. Avoid the nights of April 6 and 7, when the nearby Moon’s glare overwhelms the faint objects.

To help with your identifications, the asteroids straddle a magnitude 9.5 star April 1. Amphitrite moves a noticeable amount against the background stars each night. It heads west during April’s first half before looping south and then east, curving back toward Rho as May approaches. In contrast, we view Psyche’s orbit almost edge-on, so its westward motion appears to halt before it turns back to the east.