One luminary in this region looks different, however. If you’re new to observing, you might not even notice the object that’s not twinkling, lying to the left of the other bright stars. The steady light signifies a planet in this case, Saturn. Binoculars provide an additional treat: Saturn sits on the edge of the striking Beehive star cluster (M44). A telescope reveals the planet’s rings, which captivate even experienced observers. The best views come in midevening, once Saturn has risen well above the turbulent heat escaping from rooftops.

At the end of January, the Sun, Earth, and Saturn lined up in a configuration astronomers call opposition. During the next several weeks, look closely at where the planet’s disk blocks the rings from view. You will see a thin black line develop — the shadow of the gas giant’s atmosphere — and slowly grow as Earth’s vantage point shifts.

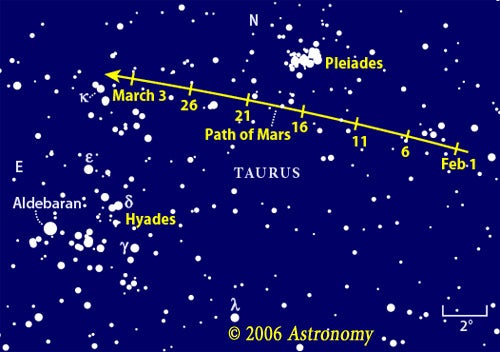

Mars glows with a fiery orange hue high in the south as darkness falls. Compare its color and brightness with nearby Aldebaran. Throughout the month, watch the planet slide eastward against the stars and south of the Pleiades star cluster (M45). This is a chance echo of Saturn’s dance around the Beehive. As enticing as Mars looks to the naked eye, through a telescope, its tiny disk will disappoint all but experienced observers and imagers. Mars’ next good visual appearance comes in late 2007.

Speedy Mercury climbs into the twilight for its best evening appearance of 2006. After February 10, point your binoculars just above the point on the horizon where the Sunset 30 to 40 minutes earlier. No bright stars lurk in this area to confuse you. During the next 2 weeks, the innermost planet climbs into a darker sky, making it even easier to see.

Spying an ultra-thin crescent Moon is a popular challenge among skywatchers. Newcomers have a chance to log a personal best February 28, when the Moon will be only 23 hours old as seen from the East Coast. Look below Mercury for a thin, Cheshire Cat smile. The next night, the lunar crescent appears more beautiful because it is filled with earthshine and set against a darker sky.

The two brightest planets rule February mornings. Jupiter rises around midnight, but it arcs low across the southern sky for northern observers. It will stay low for the next 5 years as it travels through Libra, Scorpius, Ophiuchus, Sagittarius, and Capricornus. To get the best view through a scope, wait until near dawn, when Jupiter has climbed highest. This avoids the worst atmospheric turbulence low in the sky.

Venus passed Earth on the inside of the orbital racetrack in mid-January. So when we now look toward the planet, we see mostly its shadowed side. Through a telescope, Venus’ huge, thin crescent is a sight to behold. Watch this month as the disk rapidly shrinks in size and waxes in phase.

Coursing through the pattern of bright stars called the winter hexagon, the Milky Way brightens noticeably in Gemini. A view through binoculars from under a dark sky reveals countless stars. The bright star cluster M35 stands out as a glowing patch of light.

Splendid sparkles

M35 in Gemini ranks among the sky’s finest open star clusters. In fact, observers knew of it well before it became part of Charles Messier’s famous catalog of deep-sky objects in the 1760s. Although not as prominent as the Beehive Cluster (M44), which now lurks in Saturn’s glare, M35 has a hazy glow visible to the unaided eye on a moonless night from a decent rural site.

You can see M35 through binoculars from the suburbs. The best views, however, come under a dark sky. Wait until after February 15, when the Moon no longer interferes, to see it against the rich tapestry of the winter Milky Way. Your scope will need to cool down anyway, so take a nice long look with your binoculars before jumping to the eyepiece.

Keeping this duo in mind, jump to NGC 2266, located 2° north of Epsilon (ε) Geminorum. It appears as a hazy spot through binoculars or an 8×50 finder. Located 11,000 light-years away, NGC 2266 gives an appearance halfway between the other two clusters. Notch up the power to bring NGC 2266’s fainter stars into view and see the cluster’s triangular shape.

Blast from the past

A long time ago in this part of the galaxy, the core of a massive star collapsed and blasted its outer layers of gas deep into space. Today, we can see this supernova’s remnants as a shell of expanding gas. IC 443 appears as a diffuse arc glowing with the energy released as this gas rams into the surrounding interstellar medium.

IC 443 is easy to locate but tough to see. Head to Eta (η) Gem — the star most people use to hop to M35 — and shift 0.5° east-northeast. At a magnification of 50-80x, that’s about one-half of the field of view.

IC 443’s low surface brightness renders it almost invisible straight through the eyepiece. Thanks to technological marvels called nebula filters, however, you can spy IC 443 in an 8-inch scope. Your best choice is to use a high-contrast (narrowband) filter or OIII filter. To get the most out of any nebula filter, cloak your head at the eyepiece with a dark cloth. The filter’s shiny surface reflects stray light, even at a dark site, and reduces the contrast you’re fighting so hard to enhance. If you don’t have a filter, borrow one from a fellow observer.

While you’re in this area, seek out asteroid 4 Vesta. This 7th-magnitude space rock is easy to see through binoculars from a dark site. You can find it west of Epsilon Gem.

The best evening views of Mercury this year come between February 8 and March 6. During this 4-week period, the planet sets long enough after the Sun to be seen as a bright “star” low in the western sky. On February 8, Mercury sinks below the horizon 45 minutes after the Sun. Look for it in the bright twilight about 20 minutes after sunset, when its altitude is just 4°. Its elongation from the Sun is then 10°, a value that grows to 18° by February 23/24.

After the 8th, Mercury climbs 1° higher each day. Its visibility benefits from the steep angle the ecliptic makes to the western horizon. This orientation occurs in the evening sky each February and March, and it favors the visibility of any evening planet by causing it to set longer after the Sun than at times when the ecliptic lies more horizontal to the horizon.

As Mercury climbs, it passes within 1° of distant Uranus February 13 and 14. Although this line-of-sight effect is interesting, Uranus glows dimly at magnitude 5.9 and likely will be lost in the twilight or atmospheric haze.

Mercury stands 18° east of the Sun February 23/24 at its greatest elongation for this apparition. For North American observers, the evening of February 23 should provide the best view. Mercury then shines at magnitude –0.5, and a telescope reveals its 7.2″-diameter, 50-percent-lit disk. You can capture nice images of the planet with a simple camera-on-tripod setup. The most interesting photos include striking foreground objects placed in silhouette. By the 28th, the planet fades to magnitude 0.1, while its disk grows to 8.1″ and its phase slims to a 31-percent-lit crescent.

Notice the similarity in brightness and hue between Mars and Taurus’ brightest star, Aldebaran. By the end of the month, the two appear equally bright, shining at magnitude 0.8. Aldebaran is a red giant star with a diameter roughly 50 times that of the Sun. Its red hue comes from its cool surface temperature of 6,600° Fahrenheit (3,900° Celsius). The color of Mars comes from sunlight reflecting off its non-luminous, rust-colored surface. Mars currently lies 10 light-minutes from Earth, while Aldebaran is located 65 light-years away.

You won’t find a better telescopic target this month than Saturn. It stands fairly high in the east among the background stars of Cancer the Crab once the sky gets dark. Opposition occurred in late January, so Saturn continues to shine brightly at magnitude –0.2. Binoculars will show the planet nestled against the southern edge of the star cluster M44, also known as the Beehive. Chance alignments like this add sparkle to the already beautiful telescopic visage of the ringed planet.

Saturn’s rings currently span 46″ and have never been described as bland or subtle. The rings tilt 19° to our line of sight, which affords excellent views. You should have no trouble seeing the dark Cassini Division, which separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring. And on exceptional nights, the innermost, dusky C ring comes into view.

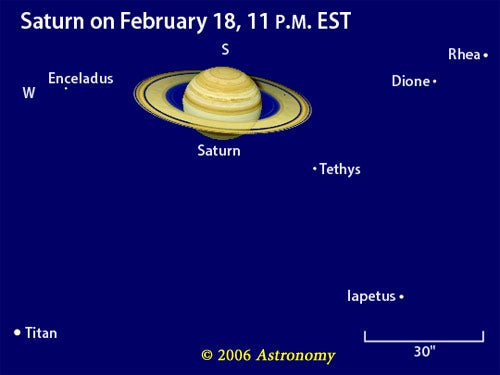

Any telescope will show Saturn’s brightest moon, Titan, throughout its 16-day orbit of the planet. Glowing at 8th magnitude, Titan is typically the brightest starlike object in the same field of view as Saturn, although field stars occasionally confuse the situation. Titan passes due north of Saturn February 2 and 18 and due south February 10 and 26.

The Cassini spacecraft has been taking spectacular images of Saturn’s smaller moons. See how many of these moons you can spot through your telescope. The easiest to see are 10th-magnitude Tethys, Dione, and Rhea, all heavily cratered worlds that orbit Saturn in periods between 2 and 5 days. Enceladus proves more of a challenge because it’s fainter and closer to Saturn. Cassini has shown this moon to be a water-rich world that is almost certainly geologically active.

Iapetus reached greatest eastern elongation from Saturn at the end of January, when it glowed dimly at magnitude 11.9. The moon brightens throughout February, however. It passes due north of the planet February 19/20 and appears brighter than magnitude 11.0 the rest of the month. You can find this moon in Titan’s vicinity February 14, 15, and 16.

Jupiter appears over the east-southeastern horizon by 2 A.M. February 1 and is 20° high by this time at month’s end. You’ll find it 6° above the Last Quarter Moon February 20.

Jupiter spends most of 2006 in the constellation Libra the Scales. Shining at magnitude –2.1 in mid-February, it dominates this region of sky.

You’ll get excellent views of Jupiter in the early morning hours. Typically, any daytime turbulence in our atmosphere has settled down by then, dust has subsided, and the spectacular winter sky beckons. The giant planet shows delicate and complex cloud patterns in its atmosphere through any telescope. Jupiter’s appearance changes every hour as the planet’s speedy rotation carries these features before us.

Jupiter spans 38″ in February and grows to 45″ by the time it reaches opposition in May. Take advantage of the dark, early morning sky to practice observing this planet and training your eye to see detail. You can also try webcam imaging. The salmon-pink Great Red Spot, a rather subtle telescopic feature by eye, shows up easily in digital images.

Jupiter passes 3′ north of Nu (ν) Librae, which glows at magnitude 5.2, February 28. Despite a similar brightness, you won’t confuse it with Jupiter’s four major moons. Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto always lie along a line passing through Jupiter’s equator, so any bright object away from this line must be a field star and not a jovian satellite. Each night, the moons’ relative positions change. Io orbits Jupiter in 1.8 days, while Europa takes twice as long. Ganymede’s orbital period, 7.2 days, doubles Europa’s, and Callisto takes 16.8 days. We see their orbits edge-on at all times, so they appear to wander east and west of the planet.

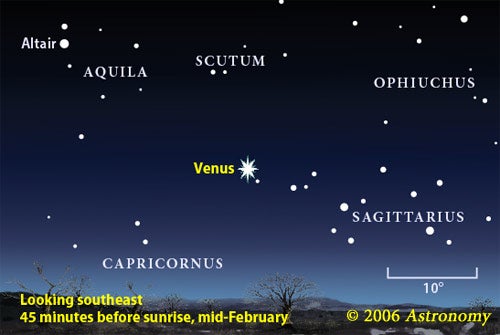

Venus lies in the constellation Sagittarius the Archer. By late February, the planet appears against a dark sky and the spectacular Milky Way — if you’re lucky enough to have clear weather and can observe away from the city. On February 24, watch shortly after 5 A.M. local time as the waning crescent Moon rises with Venus. A healthy 13° then separate the pair.

Through a telescope, Venus changes quickly this month. On February 1, the disk appears 53″ across and shows a thin, 11-percent-lit crescent. The disk shrinks all month as the distance between Earth and Venus steadily increases. Likewise, the percentage of illumination increases. On February 28, Venus shows a 34″-diameter disk that appears 34-percent lit.

Traditionally, February is a quiet month for meteors. Only one shower — the Alpha Centaurids — exists, and it’s a minor one located deep in the southern sky.

The background rate of sporadic meteors can reach as high as 7 per hour under the darkest skies. These random pieces of flotsam don’t occur with enough frequency, however, to deduce any significant meteor stream.

Occasionally, Earth runs into a large lump, and a stunning fireball erupts. Patience and good luck are the bywords for viewing meteors in February. As you watch the fine display of planets during the night, keep an eye out for that big piece of space dust that will create a brief moment of exhilaration.

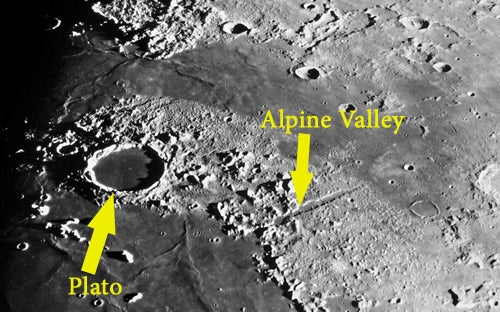

Small telescopes show the Moon’s Alpine Valley in all its glory. Also known by its Latin name, Vallis Alpes, this striking gorge slices through the lunar Alps not far east of a prominent, 63-mile-wide crater, Plato. The valley stretches 110 miles long and links the vast Mare Imbrium with the lenticular Mare Frigoris. Huge flanking mountains appear to constrict the valley at its narrow southwestern end.

Farther northeast, the valley floor opens into a wide expanse that spans nearly 7 miles. The valley floor appears dark, similar to the lava-filled maria. Running down its middle is a thin, snaking channel, or rille. It’s visible under good conditions in a 5-inch refractor and in a well-collimated 8-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain under less-ideal conditions. The Sun rises over this feature around First Quarter phase (February 4/5 this year), and changing lighting conditions reveal the valley’s full nature through Last Quarter (February 21).

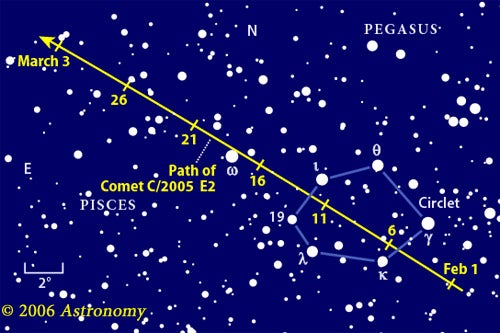

We’ve been following Comet C/2005 E2 (McNaught) for a few months now. Actually, it’s been following us — orbitally speaking — because Earth has been leading the comet around the solar system racetrack in much the same way we’re now leading Mars. Even as the comet falls behind our pace, it brightens gradually as it approaches its closest point to the Sun, or perihelion, in late February.

Bump up the magnification to 100x or so, and look for the comet’s stubby tail. If you have trouble detecting it at first, search the side opposite the Sun’s direction. The tail lies on that side because the solar wind pushes comet dust outward. Don’t forget that many scopes flip images.

Under a dark sky, you should notice a prominent naked-eye star pattern in this area: the Pisces circlet. The circlet’s easternmost star, 19 Piscium, varies slightly in brightness and shines with a lovely deep-yellow to orange hue in small scopes.

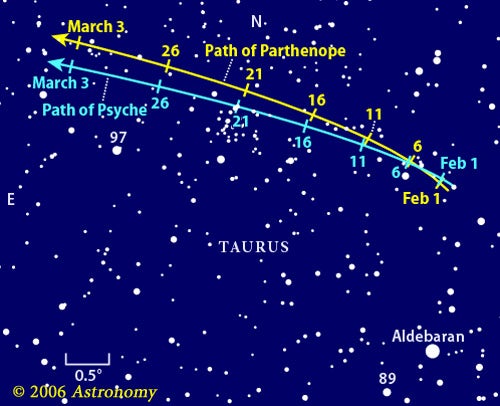

Occasionally, two asteroids lie near enough to each other that they can be viewed together. But rarely are two as close as this month’s pair. For several nights in a row, 11 Parthenope and 16 Psyche keep within 2′ of each other, less than 10 percent of the Moon’s apparent size. Their proximity is just a line-of-sight effect, however. In reality, Psyche lies 15 million miles farther away than its apparent neighbor.

The red giant star Aldebaran, the ruddy eye of Taurus the Bull, makes an easy starting point for a star-hop to these space rocks. Both asteroids glow around 11th magnitude, similar to the many background stars littering the Taurus Milky Way. To be confident of a positive identification, photograph or make a sketch of the region and return to the same spot 2 or 3 nights later. The pair’s movement should be obvious. Don’t bother trying between February 4 and 10, when light from the nearby Moon makes seeing the objects difficult.

Two other, brighter asteroids are worth tracking this month, even though they don’t lie next to each other. Asteroid 4 Vesta reached opposition January 5, so it spends February high in the evening sky. Although it has faded slightly to 7th magnitude since opposition, it should still be easy to spot through binoculars from a rural site. It’s probably too faint to see from a suburban backyard without the help of a small scope. Throughout February, it remains the fifth-brightest object in the field of Epsilon (ε) Geminorum.

Another large asteroid, 3 Juno, shares this general area of sky. Juno glows at 9th magnitude this month as it makes a beeline for Orion’s head.