We’re all excited about this extraordinary Mars opposition. That’s July 27, with Mars shining next to the Full Moon. And Mars comes closest to Earth on the 31st — the nearest martian visit since 2003. It won’t be surpassed until 2035. Very cool stuff.

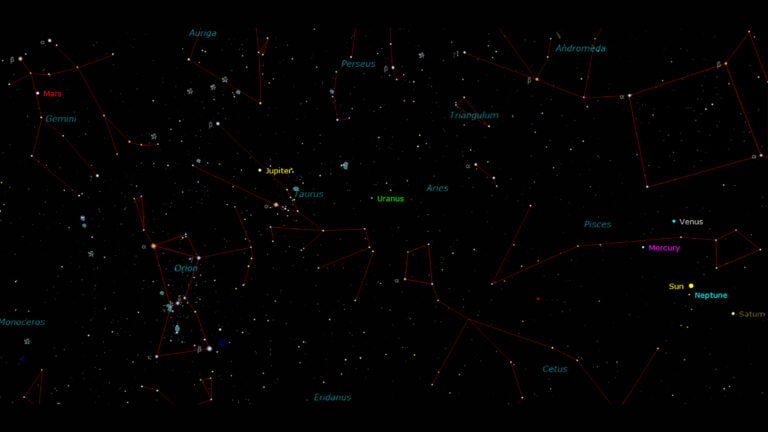

It’s a “perihelic opposition,” with Mars close to its nearest point to the Sun and Earth near its farthest, placing our two orbits at very nearly their narrowest gap. Mars at magnitude –2.8 is now brighter than Jupiter, which doesn’t happen very often. After Venus sets around nightfall, for the rest of the night, even a total newbie could find Mars just by picking out the sky’s brightest “star.” For confirmation, it’s as orange as a pumpkin — astronomy made easy.

The opposition will be a media event, and one of those cases where popular hyped astronomy is fully in sync with what we actual astronomers enjoy. Not that Mars is immune to hype. In August 2003, we had the closest martian visit in more than 50,000 years, and in the Old Farmer’s Almanac, where I’ve been the astronomy editor since forever, I wrote that through any telescope at a mere 100x, Mars would look bigger than the naked-eye Moon.

So don’t be surprised if you see that same ridiculous headline appear this year — except now, unlike all those previous summers, Mars actually has come close once again. And yes, 100x power will make it appear bigger than the Moon.

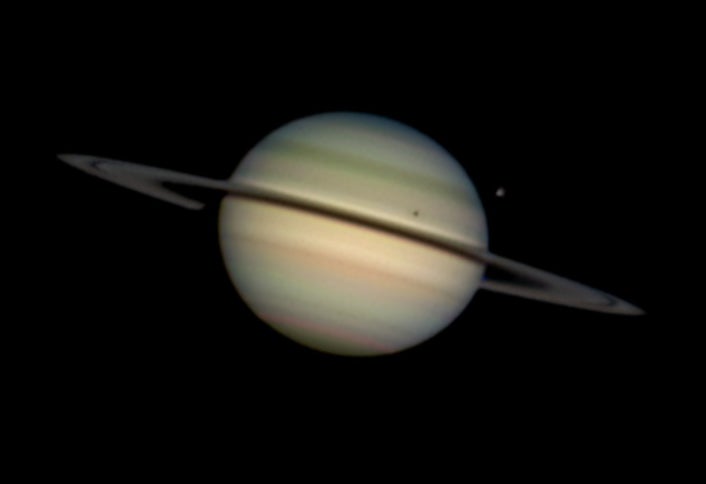

It’s fun to compare martian oppositions, which happen every 26 months, to those of, say, Saturn, which occur once a year. In both cases, speedier Earth passes the slower superior planet, making it appear big and bright for a month or two. But while Saturn always looks telescopically amazing, Mars usually has such a tiny disk that it’s hard to see detail on its 4,000-mile-wide (6,000 kilometers) body unless the opposition occurs near the narrowest gap between our orbits. And that occurs only during martian oppositions between July and October. Like right now.

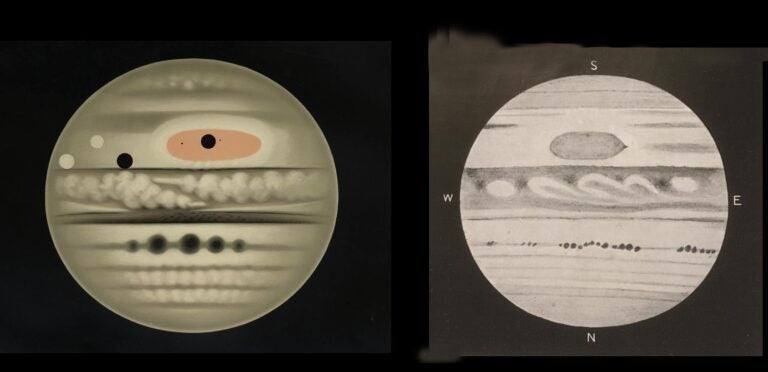

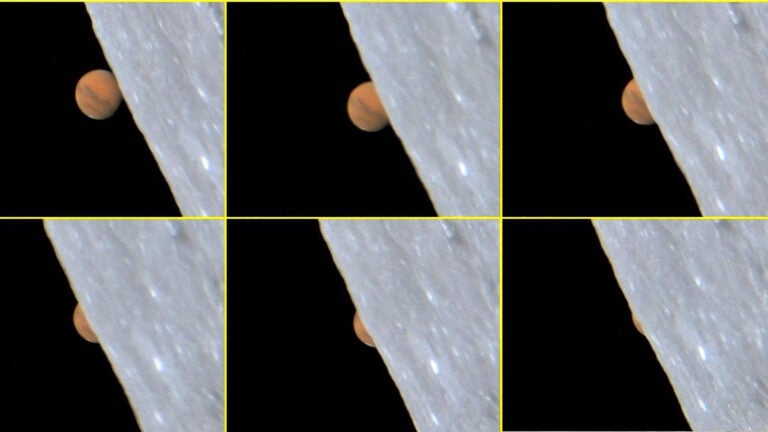

Fantastic up-close martian perihelic oppositions that happen in July and August give Mars a very high southern declination. It’s extremely low in the sky for U.S., Canadian, Japanese, Chinese, and European observers. The present martian declination of –25° makes it even lower than the winter solstice Sun. Its disk shines through three times more air than if it were high overhead, which almost always blurs the image.

This is no problem if you’re merely admiring Mars’ rare extreme brilliance. But if you’re hunting telescopically for surface detail, you need a steady night when the stars are not twinkling. Still, give it a try, because Mars appears this large only a few times in one’s life.

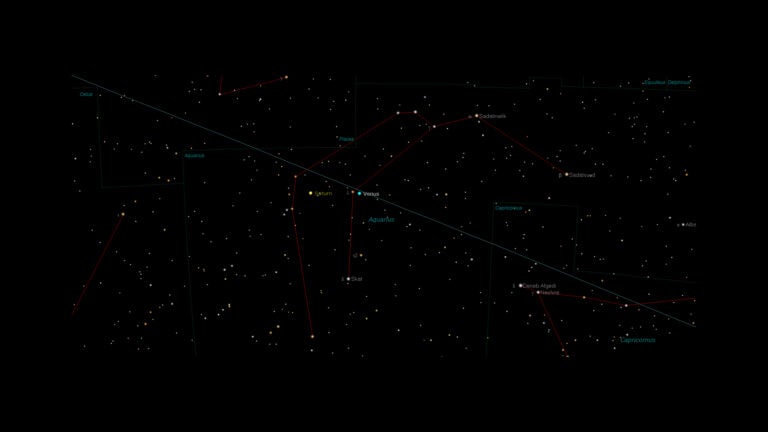

Just for fun, consider Saturn’s oppositions for a comparison. When the ringed planet comes particularly close to us, it always happens during our Northern Hemisphere winter when the planet is at its highest, in Taurus or Gemini. At the same time, its rings are always then tilted most favorably, in a maximally “open” orientation, at their best. So Saturn’s big perihelic oppositions automatically happen with optimal ring angle and maximum sky elevation. Everything comes together like gears meshing. We get three such winners, each a year apart, and then wait 27 years for the next trifecta.

By contrast, a series of two very close martian approaches, a bit more than two years apart, happens every 15 years, but with the planet mostly a low-down smudge — unless you can hang out with Aussie, Kiwi, or South African astronomers who have hit the jackpot.

Still, around here, you play the hand you’re dealt. This summer it’s the god of war at his closest and brightest.