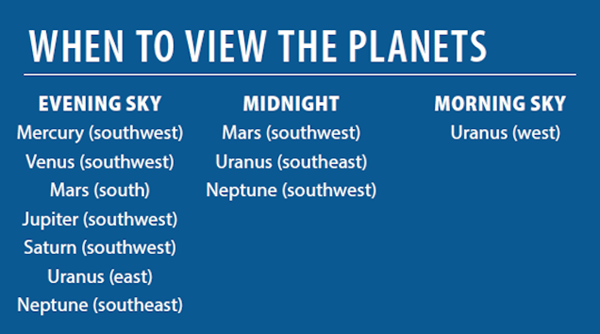

We’ll begin our tour of solar system wonders low in the west after sunset. If you’re blessed with a crystal-clear sky on the 1st, you might glimpse Uranus. Set against the background stars of southern Aries, the distant planet sets just as twilight fades to darkness. The magnitude 5.9 world appears as a faint dot through binoculars or a telescope. Uranus disappears from view after April’s first few days as it heads toward conjunction with the Sun on the 22nd. It will return to view before dawn in late May.

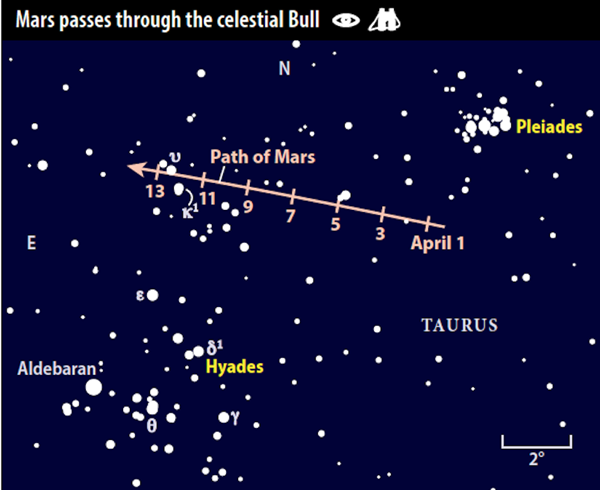

Mars fares much better than its far-off cousin. The Red Planet not only shines brightly (at magnitude 1.5 in mid-April), but it also stands quite high in the west after darkness falls. The ruddy world adds a striking focal point to the star-studded backdrop of Taurus the Bull.

Mars treks eastward through the constellation during April. It spends the month’s first week between the glittering Pleiades and Hyades star clusters. On the 1st, the planet lies 3° south of the Pleiades (M45) and some three times farther northwest of the V-shaped Hyades. Breathtaking views await those who scan this region through binoculars.

A waxing crescent Moon adds to the scene April 8. Our satellite then stands 6° south of Mars and 8° west of ruddy Aldebaran, the 1st-magnitude star that appears to anchor the Hyades but is actually a foreground object. The following night, a fatter crescent Moon lies 6° east of Aldebaran.

As Mars continues its eastward march, it passes 7° due north of Aldebaran on the 16th and traverses the open cluster NGC 1746 on the 26th. By the end of April, the planet forms an isosceles triangle with the two stars that represent the Bull’s horns: Beta (β) and Zeta (ζ) Tauri.

Mars doesn’t set until after 11 p.m. local daylight time all month. Planet watchers can then take a break before Jupiter pokes above the southeastern horizon. The giant planet rises shortly before 1:30 a.m. in early April and two hours earlier by month’s end. Gleaming at magnitude –2.3, it appears unmistakable against the backdrop of southern Ophiuchus and the magnificent central Milky Way.

Jupiter’s eastward motion relative to the Serpent-bearer’s stars comes to a halt during April’s second week. It then stands 6.5° west of the delightful Trifid Nebula (M20) in neighboring Sagittarius. Although the planet then starts heading westward against the starry backdrop, it traverses less than 1° of sky by month’s end. Be sure to mark your calendar for the morning of April 23, when a waning gibbous Moon passes within 2° of Jupiter.

The best telescopic views of the planet come once it climbs highest in the south an hour or two before dawn. It then lies nearly 30° above the horizon for observers at mid-northern latitudes. The greater altitude means that Jupiter’s light passes through less of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere and planetary details come into sharper focus.

Point any telescope toward Jupiter and you’ll see a broad disk featuring two dark equatorial belts straddling a brighter zone that coincides with the equator. Although the Equatorial Zone often appears bland, last year it sported several ocher-colored festoons. Any such features should become easier to see as the disk’s diameter swells during April, from 40″ across on the 1st to 43″ on the 30th.

Bigger scopes reveal an alternating series of more subtle dark belts and lighter zones that stretch north and south of their equatorial counterparts. Fine details along the edges of these bands pop into view during moments of good seeing.

As the innermost moon, Io orbits fastest and thus experiences the most events.

Each time Io transits Jupiter’s face, it also casts a pitch-black shadow onto the planet’s cloud tops. This month, the shadow crosses about an hour before the moon itself, and each takes about two hours to traverse the disk. For North American observers, the best shadow transits begin at 3:25 a.m. EDT on April 2, 5:19 a.m. EDT on April 9, 1:41 a.m. EDT on April 18, and 3:34 a.m. EDT on April 25.

The next moon out from Jupiter, Europa, has only one well-timed event during April. You can see its shadow first touch Jupiter’s clouds at 3:33 a.m. EDT on the 26th. The moon itself follows nearly two hours later.

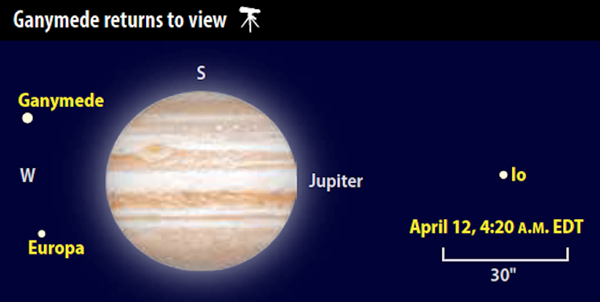

Perhaps this month’s most exciting event involves giant Ganymede. On the morning of April 12, the solar system’s largest moon starts to emerge from Jupiter’s shadow at 4:02 a.m. EDT. But Ganymede is so big that it takes 15 minutes for it to return to full sunlight. Seeing the moon slowly reappear is like watching a celestial magic act. The brightening dot appears 22″ west-southwest of Jupiter’s limb and 26″ south of Europa. Ganymede itself disappears behind Jupiter’s southwestern limb at 6:34 a.m. EDT, an event best seen from western North America.

All four moons orbit Jupiter in the planet’s equatorial plane. That plane currently tilts 3° to our line of sight, so the more distant moons cross the planet’s disk at higher latitudes. Callisto is so far out that it misses the giant world completely. You can see it near the planet’s south pole as Jupiter rises April 6, and near the north pole around dawn on the 14th.

Saturn rises shortly after 3 a.m. local daylight time April 1 and climbs some 20° high in the southeast as twilight starts to paint the sky two hours later. By the 30th, the planet clears the horizon by 1:15 a.m. and stands 25° high in the south-southeast as twilight commences. Saturn shines at magnitude 0.5 among the much fainter background stars of eastern Sagittarius. Its only real competition comes when a waning gibbous Moon appears less than 3° west of the planet April 25.

Saturn’s brightest moons are always on display. Because they orbit near the gas giant’s equatorial plane, which coincides with the plane of the rings, they all pass well north or south of the planet’s disk. Titan shines at 8th magnitude and shows up through any telescope. You can find it 1.1′ south of Saturn on April 2 and 18, and the same distance north of the planet April 10 and 26.

A trio of 10th-magnitude moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — circle Saturn inside Titan’s orbit. You’ll need a 4-inch scope to pick them out. A similar instrument should bring in distant Iapetus. This enigmatic moon, with one hemisphere as bright as snow and the other as dark as coal, stands 1.1′ south of Saturn on April 7. It then glows at 11th magnitude because we see roughly equal parts of each hemisphere. As the moon moves west of Saturn afterward, its brighter side rotates into view. It brightens to 10th magnitude by the time it reaches greatest elongation April 28, but it then lies 9′ from the planet and will be harder to identify.

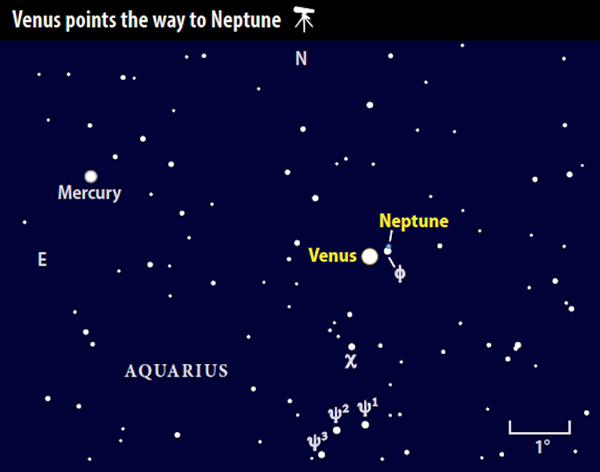

Twilight begins before the next bright planet appears. Venus rises in the east around 5:30 a.m. local daylight time April 1 and a half-hour earlier by month’s end. Unfortunately, the Sun also comes up earlier in late April, and Venus then appears deeper in twilight. Still, the inner planet shines brilliantly at magnitude –3.9 and stands out in the brightening sky.

You can use Venus to track down Neptune on April 10. The two then appear 0.3° apart and lie in the same field of view through a telescope at low power. You’ll need an exceptionally clear sky to spot 8th-magnitude Neptune, however, because it’s low and in twilight. From mid-northern latitudes, the pair stands 7° high a half-hour before sunrise. Conditions improve markedly the farther south you live; from mid-southern latitudes, the planets stand 15° high as twilight begins. Don’t confuse Neptune with the 4th-magnitude star Phi (ϕ) Aquarii, which lies 5′ south of the outer planet.

Sharp-eyed observers also should see Mercury through binoculars. The innermost planet shines at magnitude 0.3 5° east of the Venus-Neptune pair. Mercury reaches greatest elongation April 11, when it lies 28° west of the Sun but climbs only 4° high a half-hour before sunrise. Once again, Southern Hemisphere viewers have better views.

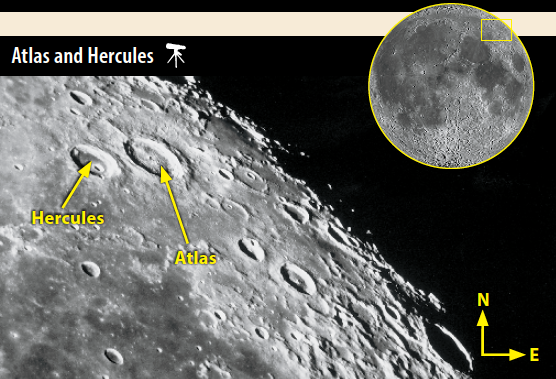

Observers of the waxing crescent Moon love spring. Naked-eye and binocular skywatchers have unparalleled views of the Moon bathed in earthshine, perched in an indigo sky painted with a horizon of fiery orange and red. Selenophiles — or “lunatics,” as friends call them — marvel at the large crater walls and mountains that cast long shadows on the lunar crescent. And the enjoyment lasts for a long time, because the Moon stands high in the twilight sky from the Northern Hemisphere, thanks to the steep angle the ecliptic makes to the western horizon after sunset. In other seasons, the crescent hangs lower and sets more quickly.

Some of the best views will come the evening of April 9. The terminator — the dividing line between sunlight and darkness on the lunar surface that marks where sunrise occurs on a waxing Moon — then cuts across the western walls of the large craters Langrenus and Petavius. Youthful Langrenus measures about 80 miles across. Although not as young as Copernicus, this crater’s features appear sharper than those of most older impact structures. A couple of prominent mountain peaks stand out at Langrenus’ center. Check back two or three nights later, and you’ll clearly see its secondary craters, debris apron, and ejecta rays.

Petavius to the south is nearly 30 miles wider, a bit older, and sports extra features. Its rim appears softer, a telltale sign of its longer life facing bombardment from solar system debris. Notice the huge radial fracture that emanates from the crater’s cluster of central peaks. Look more closely, and you should pick out a large, curved crack closer to the rim. Both of these fractures formed when lava from below heaved up the crater’s floor and later subsided.

The long wait is over. After the Quadrantid meteor display lights up early January’s sky, observers must hold out until April to view the year’s second major shower. The Lyrids peak the night of April 22/23. In the best of years, skywatchers can expect to see nearly 20 meteors per hour shortly before dawn. Unfortunately, 2019 is not the best year.

The Moon is just three days past Full at the shower’s peak and will drown out fainter Lyrids. The meteors appear to radiate from a point in the constellation Lyra the Lyre, which rises around 9 p.m. local daylight time. Although this radiant climbs 30° high by midnight and passes nearly overhead as morning twilight begins, bright moonlight fills the sky after our satellite rises around 11:30 p.m. Still, you should keep an eye out for the occasional meteor flash. Lucky observers could spot up to five per hour.

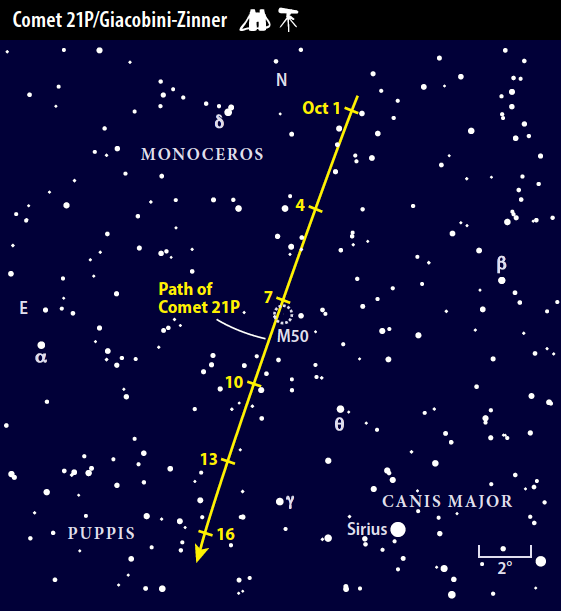

When it comes to observing comets, luck plays a role. We never know when the solar system will send us a surprise from the distant Oort Cloud, or when a periodic comet might brighten dramatically. That’s one of the lessons we can draw as we move from last autumn’s cosmic bounty to this spring’s bread crumbs.

Unless Comet C/2017 M4 (ATLAS) brightens unexpectedly, it will glow at 13th magnitude this month — a target for observers with large scopes. For the rest of us, let’s hone our skills by viewing the sky’s finest comet imposter: NGC 1931 in Auriga. The nebula and embedded star cluster lies 1° west of the bright open cluster M36.

This masquerader is bright enough to observe through a 2.4-inch telescope at 40x from under a dark sky or with an 8-inch instrument from a suburban backyard. At low power, NGC 1931 looks remarkably like a comet — it sports a relatively bright “head” and a fainter, fan-shaped “tail.” In bigger scopes, boost the power to 200x to get a closer look. The comet’s head turns out to be four closely spaced stars embedded in a cocoon of pale light.

NGC 1931 is a reflection nebula, a cloud of dust and gas that scatters starlight. Perhaps not too surprisingly, that’s pretty much what comet dust does to sunlight.

Try a range of magnifications. Although the field grows darker at higher powers, be patient and give your eye time to adjust to the reduced lighting. That’s when you can pick up finer structure that can’t be seen in a wider, brighter field.

Like spotting a lone sheep in a grassy field, it should be easy to find the 8th-magnitude asteroid 2 Pallas this month. It scoots within 5° of the sky’s fourth-brightest star, magnitude 0.0 Arcturus, the luminary of Boötes the Herdsman. Although this area remains visible all night, it climbs highest soon after midnight local daylight time.

We even get a prominent stepping-stone with magnitude 2.7 Eta (η) Boötis. On the evening of April 10, one night after it reaches opposition, Pallas slides just 2′ east of Eta. You should be able to detect its motion in as little as 30 minutes. Another good chance to see Pallas shift positions comes when it approaches a wide pair of 9th-magnitude stars April 29.

On other nights, use the chart below to figure out where Pallas will be and then swing your scope to that spot. The field will be otherwise empty from April 3–8 and 14–23. Because Pallas currently lies far from the Moon’s path, Luna’s light won’t interfere with your asteroid hunting this month.

When Heinrich Olbers discovered Pallas in March 1802, it was just the second asteroid known. (Giuseppe Piazzi spotted the first, Ceres, in January 1801.) Astronomers initially designated both objects planets, netting both discoverers considerable fame.