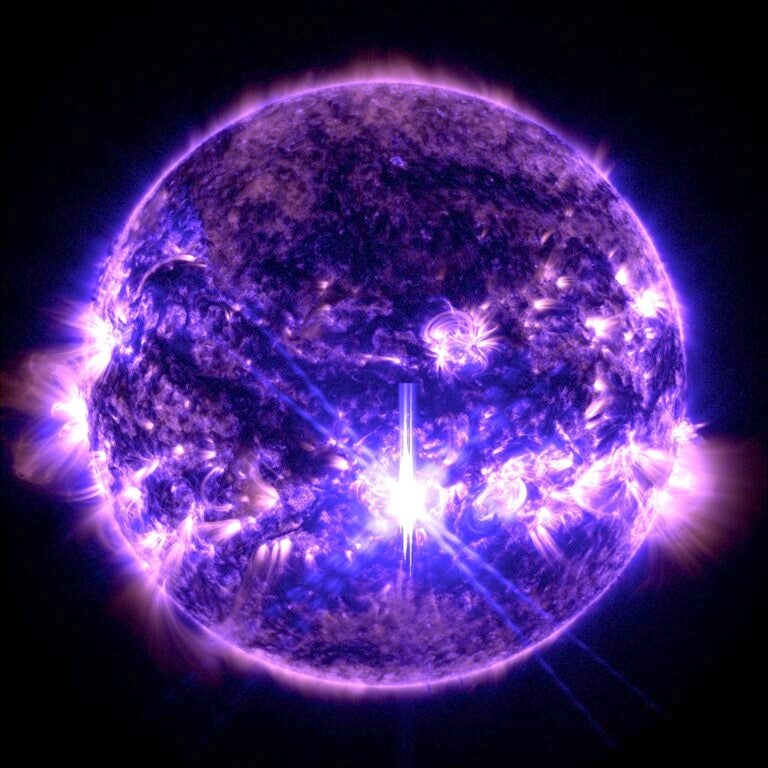

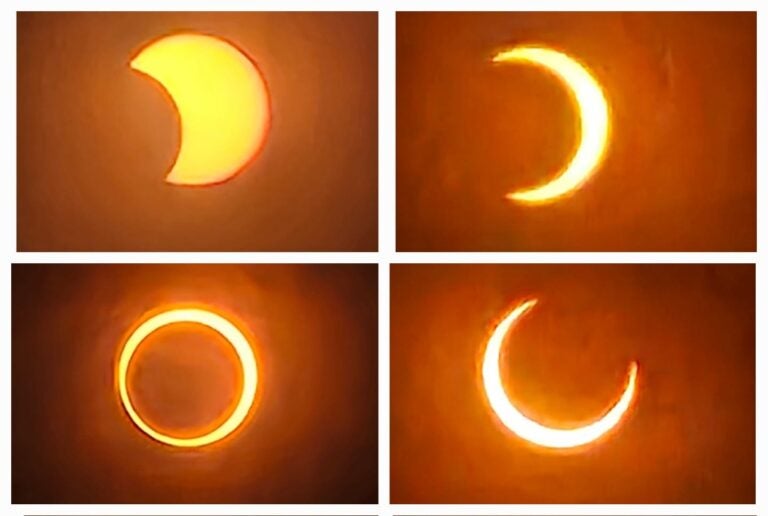

On any given day, there is a small continuous flow of natural electricity through the rocks and soil in the ground beneath our feet. This electrical current, created by changing magnetic fields in outer space and in the atmosphere, is harmless. Under certain conditions — during a geomagnetic storm — things can be very different. These storms are triggered when magnetic fields and particles from the Sun interact with Earth’s magnetic field, causing it to change quickly in the space of a few minutes. When this happens, strong electric currents high in the atmosphere can create induced currents in the ground.

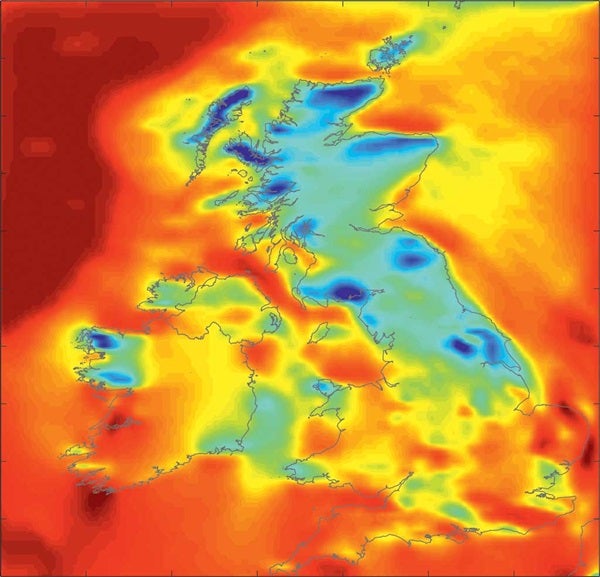

The size of the electrical currents generated depends on a number of factors, such as the local bedrock type and the amount of water within the ground. The ground currents can become large enough to potentially cause problems to technology such as high-voltage power grids, railway switches, and long pipelines.

To better understand when and how these electric currents form and flow, the BGS is now making measurements of the ground electric field at three sites in the UK (Shetland, the Scottish Borders, and Devon) — the first long-term continuous measurements of this kind in the UK. Monitoring the electric field at the three sites will help BGS predict the electric field across the entire UK, which will be used to better understand the impacts of space weather on our technology.

In their work at the BGS, Kelly and her colleagues use numerical models based on UK geology and measurements of the magnetic field to make predictions of the electric field. The new measurements of the electric field will help confirm that the model-based predictions of the electric field are correct. Knowing where large currents flow is important for reducing the potential damage to the power grid. For example, 6 million people were without power for around 12 hours in Quebec in 1989 following damage to a transformer caused when ground electricity leaked into the system after a major space weather event.

“The electric field measurement system consists of sites of two pairs of electrodes, perpendicular to each other and spaced 100 meters apart,” said Kelly. “Each electrode is buried one meter below the surface and the voltage is measured across each pair.” Although this sounds straightforward, the project could prove invaluable. “Society depends on an intricate set of electrical and electronic systems, many of which are vulnerable to adverse space weather. By measuring exactly what happens during a major storm event, we can work on better protection for our infrastructure and reduce the damage to the technology we rely on.”