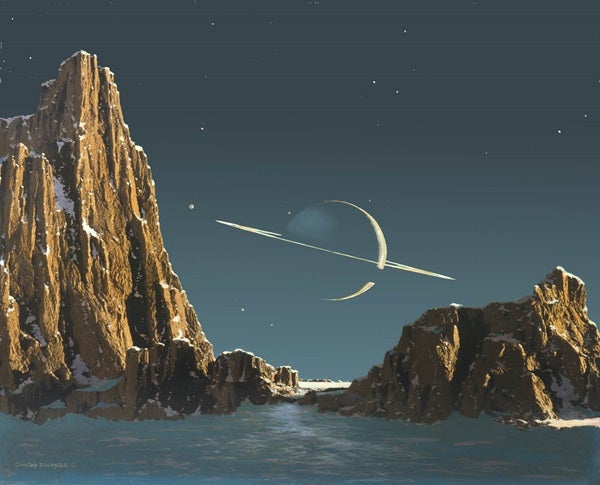

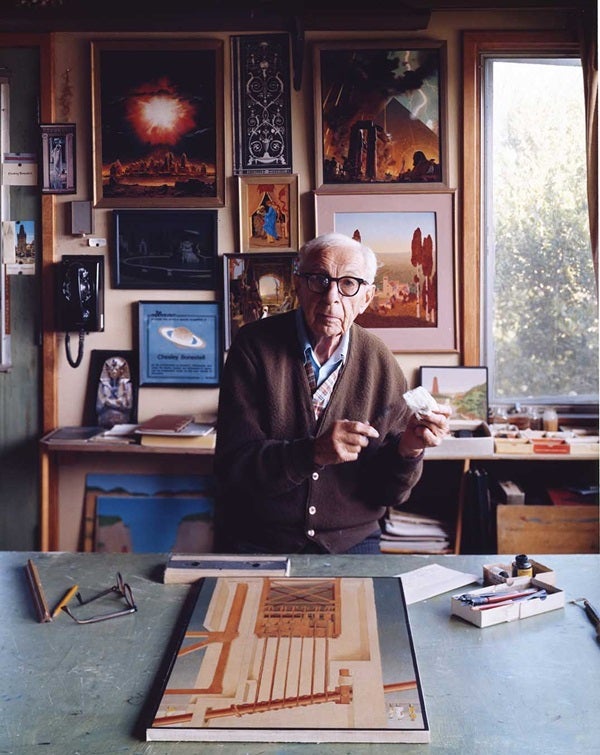

And yet, even before there were spacecraft to show us, in the 1940s and ‘50s, readers of magazines such as Collier’s, LIFE, and Sky & Telescope had a pretty good idea what kinds of scenery we might find on the Moon, Mars, Pluto, and the moons of the outer planets. All these worlds came to life in paintings by a single visionary artist: Chesley Bonestell (pronounced BONN-uh-stell). He’s the subject of a new feature-length documentary, “Chesley Bonestell: A Brush with the Future.” If you’ve never heard of Bonestell, you’ll come away from the film wondering why not. And if, like me, you knew something of Bonestell’s life and work, you’ll be astonished to discover how much more you didn’t know.

Bonestell was born in San Francisco in 1888 and survived the earthquake and fire that destroyed the city in 1906. His artistic talents were evident early. After training as an architect, he helped rebuild his hometown then moved to New York, where he worked on the Chrysler Building. After the stock-market crash of 1929 he returned to California where, among other projects, he helped design the Golden Gate Bridge. His technical drawings of the span’s support structures, and his beautiful renderings of what the finished bridge would look like, convinced skeptics that the project was both technically feasible and worth the monumental effort to erect.

In his new documentary, filmmaker Douglass M. Stewart Jr. tells Bonestell’s story largely through interviews with people whose own work was inspired by Bonestell’s. These include such luminaries as Douglas Trumbull, who created the special effects for “2001: A Space Odyssey” in 1968, and space artist Don Davis, who apprenticed with Bonestell and worked on Carl Sagan’s PBS series “Cosmos” in 1980. Unfortunately Bonestell passed away in 1986, shortly after seeing Halley’s Comet for a second time, so he couldn’t be interviewed for the film, but Stewart turned up some rare footage of him as well as an interview with Ray Bradbury in which the acclaimed author of “The Martian Chronicles” cited Bonestell as the artist whom all other science-fiction illustrators have worked to emulate.

My favorite part of “Chesley Bonestell: A Brush with the Future” was when Trumbull described how he created the lunar landscape for 2001. He modeled the Moon with smooth cratered plains and undulating hills, but director Stanley Kubrick didn’t think it looked sufficiently alien and told Trumbull to try again. What we see in the film is a forbidding landscape of craggy mountains and sharp-edged craters that looks like a Bonestell painting from the 1940s. In a brief clip from 1969 Bonestell is asked what he thought of the historic Apollo 11 Moon landing. He responds with obvious disappointment that the Moon turned out not to look as he envisioned it. It’s too bad he didn’t live to see how closely some of his other paintings, such as those of Jupiter and Saturn seen from orbit, resemble photos from subsequent NASA missions.

Most of the story-telling is done by voice-over narration, and most of the on-camera interviews show scientists, engineers, filmmakers, and artists talking about the significance of Bonestell’s work and its influence on their careers. But occasionally the film switches to an on-camera narrator, and it’s not the same person who does the voice-over. I found this a bit jarring but otherwise found the film to be informative, entertaining, and inspiring — so much so that after my wife and I saw it at a film festival near Boston, we went on Netflix to watch “The Magnificent Ambersons” (1942), another of the major movies Bonestell worked on, and one that neither of us had seen before. It was fun recognizing Bonestell’s artwork in several critical scenes.

One of the hottest areas of modern astronomical research is the discovery and characterization of planets around other stars. We know of thousands of them, and we have reason to believe there are billions more, but even today’s best telescopes show them as indistinct dots. To share with us what these worlds might actually look like, scientists collaborate with space artists such as Lynette Cook, who appears in Stewart’s documentary, to create visualizations that are as engaging as they are astronomically correct. From now on, whenever I see an artist’s imagining of a distant world, I will think of Chesley Bonestell and his remarkable legacy.

“Chesley Bonestell: A Brush with the Future” isn’t in widespread distribution yet; check the schedule of upcoming screenings here (and note that additional screenings are in the works). Meanwhile, you can view the trailer for the film here.

Rick Fienberg is Press Officer of the American Astronomical Society, former Editor in Chief of Sky & Telescope magazine, and an enthusiastic stargazer and astrophotographer.