An international team led by Lockheed Martin scientists discovered this and other findings that show how the Sun’s atmosphere is energized. The team is using the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS), which has been providing new insight into the inner workings of the Sun’s atmosphere since it launched in June 2013.

“Our results provide new insight into what drives the counterintuitive rise of temperature from the 10,000° surface to millions of degrees in the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona,” said Bart De Pontieu from IRIS.

To address this long-standing problem, NASA launched IRIS, an Earth-orbiting small explorer satellite with a 7.9-inch (20 centimeters) telescope on board, which was built by Lockheed Martin.

“IRIS splits the Sun’s near- and far-ultraviolet light into its constituents in order to remotely probe the physical conditions in the interface region,” De Pontieu said.

The interface region consists of the relatively cool chromosphere (10,000°–20,000° F [5,500°–11,100° C]) and transition region (a few hundred thousand degrees). Recent research suggested that it is here, at the interface between surface and corona, that answers to some of the more vexing unresolved questions in solar physics might be found.

“Our findings can apply beyond our solar system,” said Alan Title from IRIS. “The physical processes that occur in our Sun can occur in other much more distant stars, so this is a local laboratory for wide-ranging discovery.”

IRIS discoveries

Details of these discoveries are in a new issue of Science. Five articles leverage high-resolution IRIS images and spectra to present major advances in understanding how the solar atmosphere is energized.

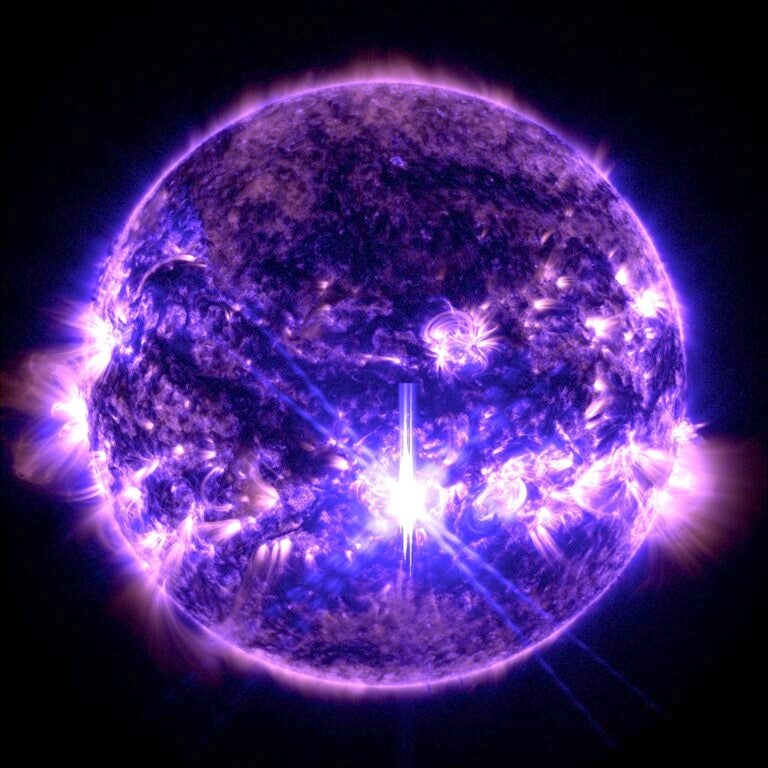

* Nanoflares: Scientists find compelling evidence for the presence of high-energy particles generated during coronal nanoflares. These are small-scale events long thought to drive coronal heating through the release of energy when magnetic field lines reconnect. This result provides new insight into how these electrons are accelerated to such high energies.

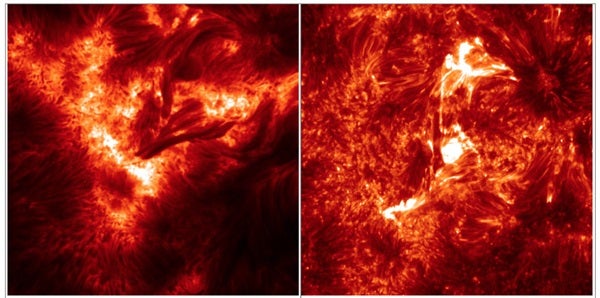

* Transition Region Loops: Small-scale magnetic loops were found in high-resolution images of IRIS and advanced 3-D models, resolving a long-standing debate about the nature of the emission in the transition region. These results vindicate a view that this emission does not originate in the usual transition region between the surface and hot loops, but occurs in previously undiscovered loop-like structures.

* Solar “Bombs”: Researchers saw in high-resolution spectra a solar atmosphere turned upside down: hot plasma at 100,000 kelvin is found closer to the solar surface than previously imagined. The plasma is sandwiched by cool plasma both below and above and heated by “bombs” where magnetic fields reconnect and lead to rapid heating. These unexpected results will likely lead to a reassessment of other phenomena in the low solar atmosphere, such as the mysterious Ellerman bombs discovered almost a century ago.

* Jets in the Wind: Scientists uncover evidence of high-speed jets at the root of the solar wind, a high-speed, continuous stream of particles that permeates space around Earth. The jets are fountains of plasma that appear to undergo rapid heating from 20,000°–180,000° F (11,000°–100,000° C) and may provide hot plasma to the solar wind.

* Twist: As described above, one paper shows the chromosphere is full of twisting motions on spatial scales of a few hundred miles. These motions are a sign of magnetic waves and support recent theories about heating of the solar chromosphere and corona.

Together, these results provide critical pieces in the still-unsolved puzzle of how the Sun shapes and affects the heliosphere, the Sun’s outer atmosphere in which we live. With solar activity at high levels, scientists are expecting more advances from the imaging spectrograph on board IRIS, especially regarding solar flares and coronal mass ejections, which are violent explosions that cause bouts of bad space weather that threaten power grids, satellites, and astronauts.