Known as the Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope until South Africa assumed two-thirds ownership in 1972, the observatory became so synonymous with this picturesque corner of Cape Town that the surrounding area appropriated its name. Say “observatory” to most Capetonians now and they’ll direct you to an eclectic and bohemian conurbation bordering the Salt River in the northeastern corner of the Western Cape. The SAAO itself is tucked quietly away on a hill in this suburb, calm and stately on a cool and sunny August day, the dramatic mountainscape of Devil’s Peak and Lion’s Head puncturing the sky on the western horizon.

Two centuries ago, the lush trimmed lawns of the SAAO complex were cattle pastures surrounded by disease-ridden swamps, the main building still a twinkle in the eye of a naval power casting increasingly amorous eastward glances. The British Empire invaded the Cape in 1806, and its navy needed a Southern Hemisphere observatory somewhere along its trading route to the Orient. Exploration of choppy southern waters could be perilous, and the development of sophisticated navigational equipment was still in its infancy; ships could sometimes find themselves hundreds of miles off-course.

The accurate resetting of chronometers required reliable time signals from a static station; scientists based at the proposed observatory would measure time using pendulum clocks and star positions, providing a standard chronological marker for vessels moored in Table Bay. This time would then be visually communicated to the ships by firing a flare pistol and dropping a colorful time ball on the observatory grounds (a cannon is still fired every day at noon on Signal Hill near Table Mountain).

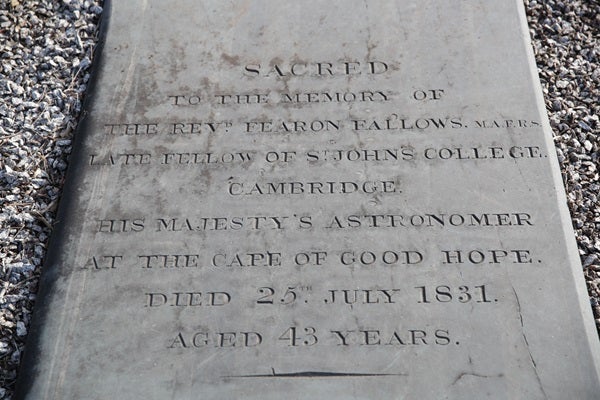

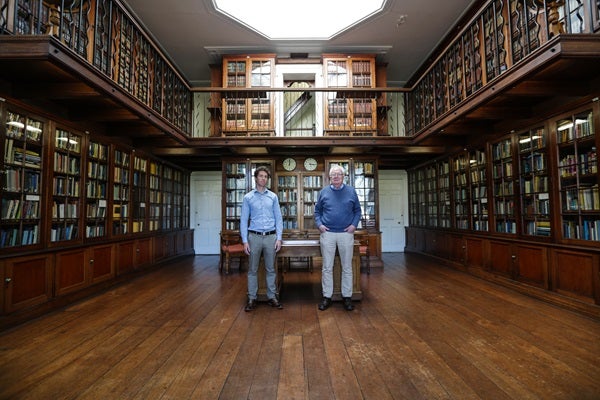

So it was perhaps fortuitous that imperial demand had overlapped with scientific appetite, which had long coveted an opportunity to properly map the Southern Celestial Hemisphere. Few, however, would volunteer to undertake the grueling task of overseeing the construction of the initial buildings and taking receipt of the first items of equipment. This responsibility fell to a British mathematician with the swashbuckling name of Fearon Fallows, who survived in the feverish and insanitary conditions just long enough to witness the completion of the main building — an impressive classical structure with teak floors and window frames, which now accommodates the observatory library (home to a 500-year-old copy of Ptolemy’s Almagest).

Over the course of its close to 200-year history, the observatory has hosted an impressive array of scientific trailblazers. Thomas Maclear, His Majesty’s Astronomer between 1833 and 1870, modified the famous French astronomer de la Caille’s assertion that Earth was pear-shaped (Maclear showed it is oblate and symmetrical, though American astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has recently suggested it may indeed be slightly portlier below the equator).

“They employed a lot of people called computers — that was their job, to just work out figures,” says Glass. “And they mostly wanted youngsters who had a good head for figures, but they would go crazy after a few years — they wouldn’t last very long doing this. Then photography became the technique of choice, and this place became a world center for photography, so some of the earliest photographic sky maps were made from here.”

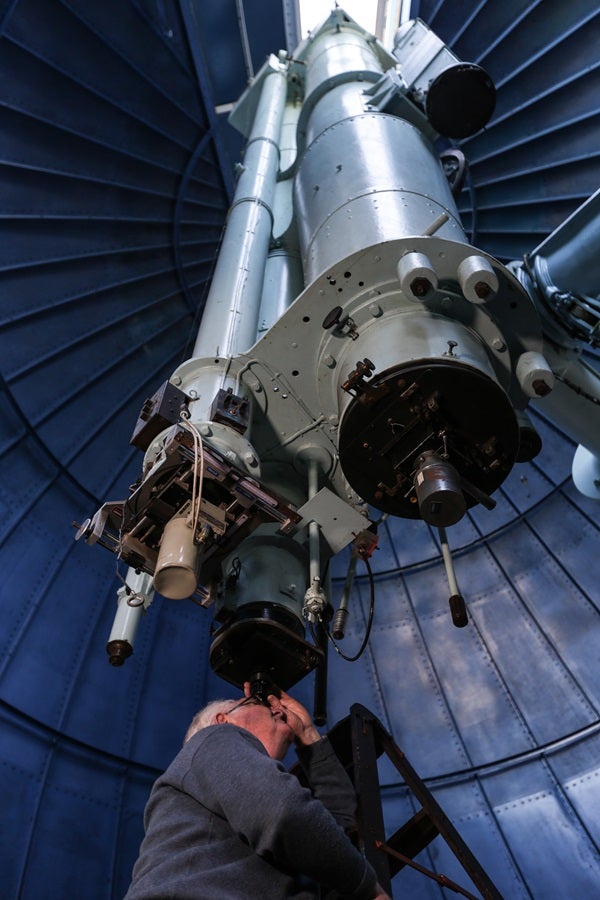

In 1896, Gill secured funding for the construction of the 36-foot McClean Dome, which houses the Victoria Telescope, the largest on the compound. The trichotomic telescope was retired in the early 80s but remains fully functional, and the star of the regular open nights co-organized by Dr. Daniel Cunnama, a computational astrophysicist who also contributes to the observatory’s busy outreach program.

The observatory also embraces concepts rooted in ethnoastronomy, an important allegorical compass for many African cultures with its own intricate cosmology of meanings and function. “I think it’s very important to understand it and engage with it, rather than push against it,” Cunnama says. “This sort of indigenous knowledge, these beliefs and understandings of the stars, of the universe, they’re important, in the same way that in western civilization we take for granted the cultural or societal knowledge we have, which isn’t necessarily taught at school. To not incorporate other societies’ cultural knowledge into your teaching is very short-sighted.”

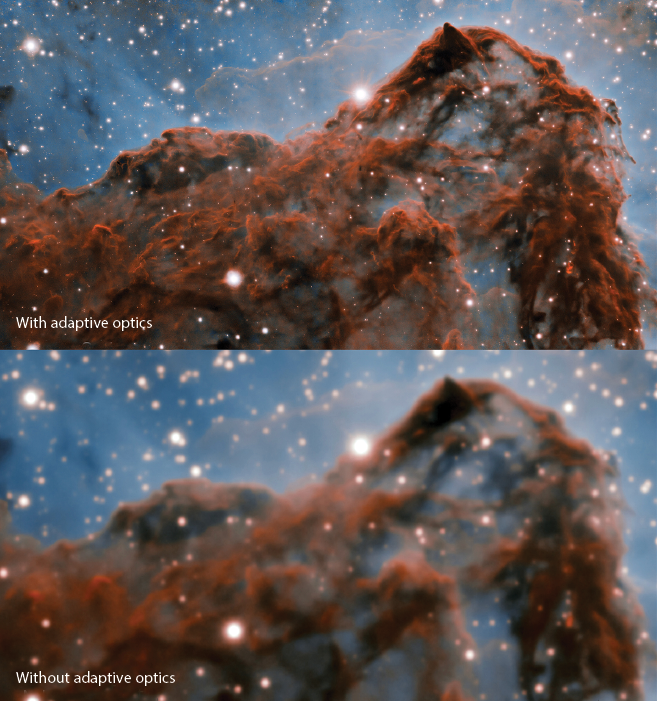

“Faced with the task of having so much data, one individual human cannot process that sort of information,” says Cunnama. “You can’t look at 100 million galaxies and try and work out what is interesting. Whereas if you can have some kind of machine learning algorithms that can process this data, look for interesting features, and identify them for you, you can then maybe understand better what’s going on.” Global astronomy’s mothership project, the jointly-financed Square Kilometer Array, is set to plant one foot in the Karoo in 2018, and is projected to boast the computing power of 100 million PCs.

“The thing about discoveries is that you don’t know what to expect,” says Glass. “There’s always a problem when you have a new instrument like SALT or the SKA — you expect because of its sheer size it’s going to find newer, fainter, more distant things, but you don’t know ahead of time.”

He’s about to be interrupted by the boom of the noonday gun on Signal Hill, 25 seconds away.

Dr. Glass’ book, The Royal Observatory at the Cape of Good Hope, can be purchased by contacting Dr. Glass at isg@saao.ac.za.