Orion the Hunter has a treat in store Friday morning, when the annual Orionid meteor shower will send tens of meteors streaking across the sky each hour before dawn. The Orionids are a favorite fall tradition for many amateur astronomers, but you don’t need to be a seasoned observer — anyone can easily catch this stunning show.

When, where, and how to watch

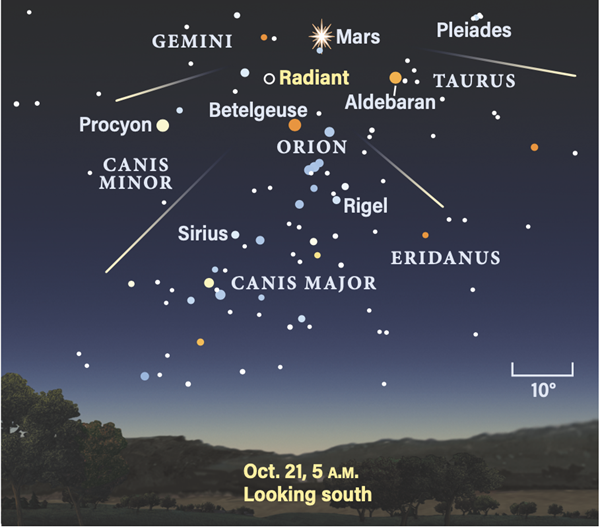

This year, the popular shower peaks the morning of Friday, October 21. The best time to watch for shooting stars is in the hours between about 2 A.M. local time and dawn. That’s when the radiant, or point from which shower meteors originate, is highest. The radiant is located in the southern sky, slightly northeast of bright Betelgeuse, Orion’s red shoulder star. The chart below will show you where to look around 5 A.M. local time on Friday morning, though the radiant may be slightly lower or higher depending on your latitude. You can also use this chart for several days after Friday, as the early-morning sky will look much the same.

This year, the maximum expected zenithal hourly rate, which is the highest rate of meteors you could expect to see if the radiant were 90° overhead, is 20 meteors per hour. However, the radiant won’t reach 90° high during dark hours, so you can instead expect to see some 15 to 18 meteors per hour before dawn. Although a crescent Moon rises around 3 A.M., its feeble light won’t interfere much in your meteor search.

To spot the longest trains, which are the bright streaks left behind as a meteor burns up, first find the radiant and then cast your gaze away from it. Why look away? Because meteors originate from the radiant point, trains in that region of the sky are shortest. But look about 45° to 90° from the radiant in either direction, and you’ll see much longer trains. These streaks form as the meteorite vaporizes on its way into the atmosphere and typically last for about a second or less.

The Orionids arise from the dusty debris left by arguably the most famous comet of all time: Halley’s Comet. Every time Halley rounds the Sun, it leaves behind a trail of dust particles in its wake. When Earth passes through this trail in the fall, we experience the Orionids. (When we cross through it again in the spring, we see the Eta Aquariids.) Although the shower peaks Friday morning, it will remain active through early November. So, if you can’t make it outside during the peak, you’re still more likely to see several shower meteors per hour over the next few mornings as well, though their numbers will diminish with time.

Because it’s getting chilly outside, make sure to bundle up — after all, the best way to see the most bright meteors is to be patient and scan the sky for an hour or more, rather than simply stepping out, looking up, and ducking back inside. Several layers and a hot drink can make your meteor-watching morning much more enjoyable. If you have a comfortable chair and some blankets, get yourself settled so you can lean back and look at the sky with even less effort. You won’t need a telescope or binoculars to enjoy the show — this celestial event is best seen with your naked eyes.

Sunrise: 7:17 A.M.

Sunset: 6:11 P.M.

Moonrise: 3:03 A.M.

Moonset: 4:44 P.M.

Moon Phase: Waning crescent (15%)

*Times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise, and moonset are given in local time from 40° N 90° W. The Moon’s illumination is given at 12 P.M. local time from the same location.

Much more to see

While you’re waiting for shooting stars to appear, there’s plenty else to enjoy in the morning sky. First off, there’s a bright trio of orangey-red objects on Friday morning: In addition to Betelgeuse in Orion, Taurus the Bull also hosts a famous red giant star, Aldebaran. And the mighty Red Planet Mars, glowing at magnitude –1, is also currently in Taurus, some 16° northeast of the Bull’s red eye.

Look about 25° to the left (north-northwest) of Mars, and you’ll land on the Pleiades star cluster (M45), a young grouping of bright, glittering stars. Some seven or so young suns are visible to the naked eye, and many people mistake them for the Little Dipper because they form a tiny spoon-shaped pattern. (The true Little Dipper, however, is over in the northern sky, its handle curving down from Polaris, the North Star.) The Pleiades isn’t the only young open cluster in Taurus — look to Aldebaran and nearby you’ll notice a spread-out sprinkling of stars. These are the Hyades, a slightly older open cluster.

Look back to Betelgeuse and drop down toward the horizon to spot one of the sky’s most famous asterisms, Orion’s Belt. Below the leftmost (southeasternmost) star is the Orion Nebula (M42), visible as a dim, dusky patch to the naked eye. Here, you’ll want to pull out binoculars or a telescope to enjoy its intricate structure, formed by gas and dust that is slowly creating new stars.

The Orionids are a wonderful fall tradition to observe, and this year’s show promises to be a good one. So, this Friday, grab your scarf and top off your morning joe, and enjoy!