According to Astronomy magazine senior editor Richard Talcott, conditions should be good this year. “Although a waxing crescent Moon will share the sky with the Orionids before midnight, people will be looking away from it. The Moon shouldn’t cut the number of visible meteors by more than 20 percent.”

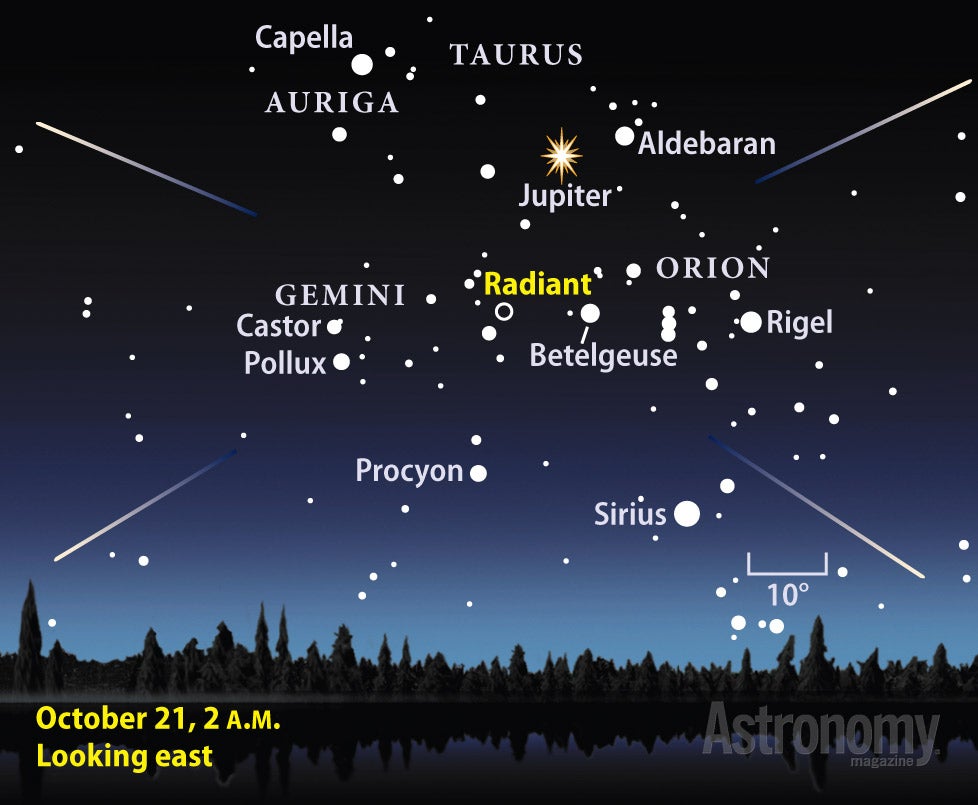

The radiant — the point in the sky where all the meteor trails trace back to — lies in northeastern Orion the Hunter, where that constellation borders Gemini the Twins. The Orionids’ radiant rises before midnight and stands high in the south by 4 a.m. local daylight time, a full two hours before dawn. This year, viewing conditions are favorable. At the shower’s peak, the waxing crescent Moon sets well before the prime observing hours after midnight.

Rates can reach 30 meteors per hour, and occasionally more. The predawn hours offer the best viewing because that’s when your location will face Earth’s direction of travel. Essentially, after midnight Earth will be running into the meteors.

The shower remains active all month, beginning October 2 and ending November 7. Meteor rates start and end with a trickle, but they achieve a substantial peak October 20/21. (The 1993 and 1998 Orionid showers showed higher rates three to four days earlier, so it’s worth watching the shower before its predicted maximum.)

Earth’s upper atmosphere at 148,000 mph (238,000 km/h). Many leave

persistent trains — glowing tubes of ionized gas created by the dust

particles burning up.

All Orionid meteors originate from debris

left behind by Halley’s Comet during its passages through the inner

solar system. Earth’s orbit intersects this debris trail in two places,

resulting in this fine autumn shower and another good one in May called

the Eta Aquarids.

It’s best to view meteor showers without

optical aid because binoculars or a telescope restrict the field of

view. If you must observe before midnight, face eastward and look about

halfway up. From midnight to 2 a.m. local time, looking overhead will

probably net you the most meteors. And from 2 a.m. until dawn, look

roughly halfway up in the west. Glancing around now and again won’t hurt

your chances of seeing the maximum number of meteors.

Meteor

showers are great social and family events. This year’s Orionids peak on

a Saturday night/Sunday morning, which makes getting a group together

easier. Head out of town to a dark location. Bring lawn chairs, sleeping

bags, and hot drinks to stay warm. Plan to wear winter gear — many

observers are surprised at the chill of autumn’s late-night air.

Fast facts:

- At

148,000 mph (238,000 km/h), Orionid meteors are the second-fastest of

any annual shower. Only the Leonids of November hit our atmosphere

faster, at 159,000 mph (256,000 km/h). - The Orionid meteor shower

is one of two that derive from Comet Halley’s debris. The other is the

Eta Aquarid shower, which peaks in May.

- Video: How to observe meteor showers, with Michael E. Bakich, senior editor

- Video: Easy-to-find objects in the 2012 autumn sky, with Richard Talcott, senior editor

- StarDome: Locate the shower’s radiant in Orion in your night sky with our interactive star chart.

- The Sky this Week: Get your Orionid meteor shower info from a daily digest of celestial events coming soon to a sky near you.

- Sign up for our free weekly e-mail newsletter.