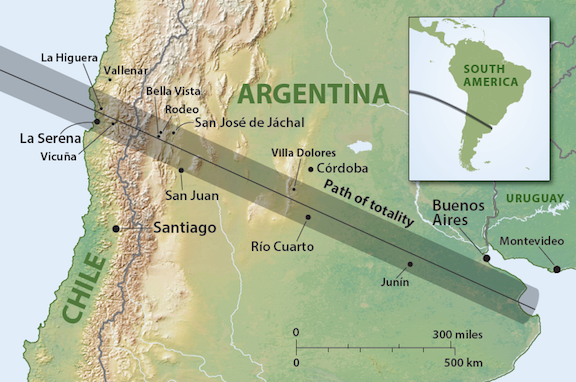

As it turns out, the next total eclipse of the Sun occurs July 2, 2019. Its path starts in the South Pacific near Pitcairn Island and ends over land, having touched just two countries: Chile and Argentina.

Totality of the 2019 eclipse will be 70 percent longer than the 2017 event. This is because Earth is not always at the same distance from the Sun, and the Moon is not always the same distance from Earth. Since the Earth-Sun distance varies by 3 percent and the Moon-Earth distance by 12 percent, the length of totality fluctuates from one eclipse to the next. So, while the eclipse of August 2017 had a totality lasting 2 minutes 40 seconds, the next one will be a bit longer.

Maximum eclipse, a worthy 4 minutes 33 seconds, occurs over water 665 miles (1,070 kilometers) north of Easter Island — and some people may travel there to experience that length of totality. Most people who want to see this eclipse, however, will be standing on terra firma, and that means South America.

The central path of the Moon’s shadow first touches Chilean soil at 19h22m38s UT, just south of the berg of Chungungo, which has a population under 400. If you’re in that small village, totality will last 2 minutes 36 seconds. You’ll lose only 0.3 second off the central path’s time.

Some tourists will no doubt head for the centerline in or near La Higuera, a town of about 4,300 inhabitants. Totality here also lasts 2 minutes 36 seconds. If you travel north along Chile Route 5, La Higuera is a five-and-a-half-hour drive from Santiago.

Most travelers probably will opt to stay in La Serena, which lies only 38 miles (61 km) south of La Higuera. With a population near 200,000, it’s the fourth-largest urban area in the country. There, eclipse seekers will also find lodging, transportation options, fine dining (including terrific local cuisine), and more. And if by chance you find yourself stuck in the city on eclipse day, you’re not out of luck. The Moon’s shadow will cover La Serena for 2 minutes 13 seconds.

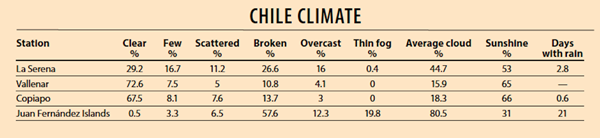

Observations from La Florida Airport, about 4.5 miles (7 km) inland from the coast at La Serena, show that the city receives only about 53 percent of the maximum possible sunshine during the month. Cloud cover is about the same, with an average amount of 45 percent at 21h UT. (Totality is at 20h39m UT, or 4:39 P.M. local time.) Despite these somewhat pessimistic statistics, a frequency graph of daily sunshine hours for the city (see the chart on p. 53) shows a large number of clear or mostly clear days.

Anderson says most of the clouds at La Serena come from the marine stratus that pushes on shore, but satellite observations show that the clouds typically evaporate around noon. A large number of days have four or more hours of sunshine, and most of these hours are in the afternoons.

If eclipse day promises to be sunny along the coast, La Higuera may prove particularly attractive. It’s protected from the marine cloudiness by a range of 3,000-foot-high (1,000 meters) hills that lie near the coast. When the coast at La Serena is overcast, La Higuera may be clear, although it would be unusual for clouds to persist to eclipse time in either location.

Argentina

As the path of totality leaves Chile, it enters Argentina. This marks the eclipse’s last leg. The centerline actually crosses the point where Chile Highway 41 becomes Argentina Highway 150. And because we’re approaching the endpoint of the eclipse, the maximum durations of totality continue to shrink as the path treks to the southeast.

The small hamlet of Bella Vista is the first place eclipse chasers may head. There, you’ll experience 2 minutes 30 seconds of totality. Bella Vista lies 20 miles (32 km) from the sizable town of Rodeo and 50 miles (80 km) from the much larger San José de Jáchal. The two communities have good visibility west toward the sinking Sun (11° high at mid-eclipse). Another option for lodging is San Juan, which boasts a metropolitan area of 500,000 inhabitants and lies about 100 miles (160 km) away.

Buenos Aires offers a lot to tourists. And indeed, the southwestern outskirts of the city do get about 50 seconds of totality. But — you guessed it — the Sun at mid-eclipse stands a meager 1° above the horizon.

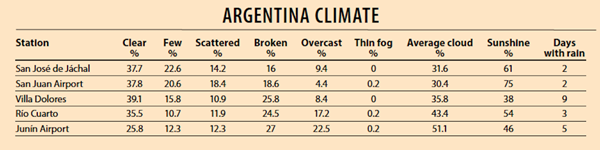

For what travelers can expect from the weather in Argentina, we turn once again to Jay Anderson. He says that the available evidence — satellite and ground-level measurements — points to a location against the eastern slopes of the Andes as having the best chances of seeing the eclipse. In particular, Bella Vista and Iglesia to its north lie on an open plain where satellite imagery promises the lowest average cloud amount anywhere along the track.

July finds this region in the middle of winter with little precipitation. But although the climate is dry, the terrain still has a modest effect on clouds. From a minimum of about 28 percent at Bella Vista, the cloud cover rises a fraction at San José de Jáchal and then climbs more distinctly to 43 percent at Río Cuarto.

Bella Vista, along with Iglesia and Rodeo, lies in a deep, narrow, north-south tectonic valley. The valley has a climate and geography comparable to that in Death Valley, California. It has one of the driest and sunniest climates in Argentina. So, if you plan to observe from there, make sure the eclipsed Sun won’t slip behind a mountain.

Two editors from Astronomy are headed south to experience the eclipse. Associate Editor Jake Parks will be the astronomer for TravelQuest International, the magazine’s partner on such trips. His group will first visit Peru, where it will tour Machu Picchu, Cuzco, and other sites. At the time of this writing, only a few spots remain in his group, so it’s likely not an option for last-minute planners.

I’m heading to northern Chile with a group of about 20 intrepid eclipse chasers. I’ve recruited several friends and eclipse photographers (among them Astronomy Contributing Editor Mike Reynolds), so I’m just going to sit back and watch. We’ll travel in large vans, so on eclipse day we can change our location if clouds intervene.

On July 2, I’ll witness my 15th total solar eclipse. I’ve written numerous stories and even a book about these events, so I feel qualified to offer a few words of advice.

My first point cannot be overstated: The only time you can view the Sun safely with the naked eye is during totality. It is never safe to look at a partial or annular eclipse, or the partial phases of a total solar eclipse, without the proper equipment and techniques. Even when 99 percent of the Sun’s visible surface (the photosphere) is obscured during the partial phases of a solar eclipse, the remaining crescent Sun is still intense enough to cause a retinal burn. So, protect your eyes!

Second, if you plan to photograph the eclipse, rehearse. Set up the exact equipment you’re taking and photograph the Sun. Of course, you’ll do a few things differently on eclipse day. The one to be sure of is that you take the solar filter off your telescope or camera lens at the start of totality — or, as many imagers do, just prior to the first diamond ring. You’ll also change the exposure times once the Moon hides the brilliant solar disk. Because the Sun’s corona is the same brightness as the Full Moon, you can practice those exposures (under similar lighting) on it.

Finally, if you’re planning to photograph the event and anything goes wrong . . . stop! Just back away from your equipment and watch the eclipse. The maximum duration of totality is a scant 273 seconds, and that’s from a ship on the ocean. On land, it’s about half that. Really, how many problems do you think you can fix in two minutes? Sure, you might not get the classic shot of the corona, but you’ll still have a memory that will last a lifetime.