Let’s kick off our planet viewing this month with a final glimpse of Mars. The Red Planet lies low in the west-northwest after sunset in early June. You’ll likely need binoculars to spot the magnitude 1.7 object against the twilight glow. Scan for it well below and a little to the right of Gemini’s twin stars, Castor and Pollux. Mars becomes lost in the Sun’s glare during June’s second week and won’t return to view until September.

You’ll have no such trouble finding Jupiter. The giant world blazes at magnitude –2.2, far brighter than any other evening object except for the Moon. You can compare these two standouts June 3, when the waxing gibbous Moon passes 2° from the planet. The stunning pair stands high in the south after sunset and remains on view until well past midnight.

Jupiter appears nearly stationary against the background stars of Virgo the Maiden during June. It starts the month 3° southeast of 3rd-magnitude Gamma (γ) Virginis. The planet’s glacial westward motion comes to a halt the night of June 9/10; it then begins a slow eastward trek that carries it 4° from Gamma by the 30th. The Moon returns to this vicinity that same night, and actually passes in front of Gamma for observers across much of North America.

It’s always worth exploring Jupiter through a telescope. Catch it during the evening hours this month — seeing conditions deteriorate when it dips low in the west after midnight. The planet spans 39″ at midmonth and offers lots of detail to patient observers. Any instrument should reveal Jupiter’s two dark equatorial belts, one on either side of a brighter equatorial zone coinciding with the planet’s equator. In moments of good seeing, a series of alternating belts and zones comes into view. And keep an eye out for the Great Red Spot — it shows up clearly as long as it’s on the hemisphere facing Earth.

As darkness falls the night of June 1/2, Io and Europa both lie off the planet’s eastern limb. Europa begins its transit at 1:18 a.m. EDT and Io follows 80 minutes later. Europa’s shadow appears on the jovian cloud tops starting at 3:31 a.m., with Io’s shadow trailing 11 minutes behind.

Io teams with Ganymede’s shadow the night of June 3/4. Io strikes first, crossing in front of the planet’s eastern limb at 9:06 p.m. EDT. The moon’s shadow appears beginning at 10:10 p.m. Eleven minutes later, Ganymede’s large shadow initially falls on the gas giant’s north polar region. These shadows dramatically alter Jupiter’s appearance all evening. Io’s transit ends at 11:16 p.m. Its shadow lifts back into space at 12:21 a.m., and Ganymede’s shadow follows 16 minutes later.

Three moons take center stage the night of June 10/11. In eastern North America in the early evening, Ganymede and Io appear against Jupiter’s disk. Ganymede exits at the stroke of midnight EDT, five minutes before Io’s shadow appears at the opposite limb. Io’s transit ends at 1:07 a.m., while its shadow remains on the planet’s disk until 2:15 a.m. Ganymede’s shadow starts a transit five minutes after that. The night’s final event occurs around 3:10 a.m., when Europa emerges from Jupiter’s shadow some 30″ from Jupiter’s eastern limb.

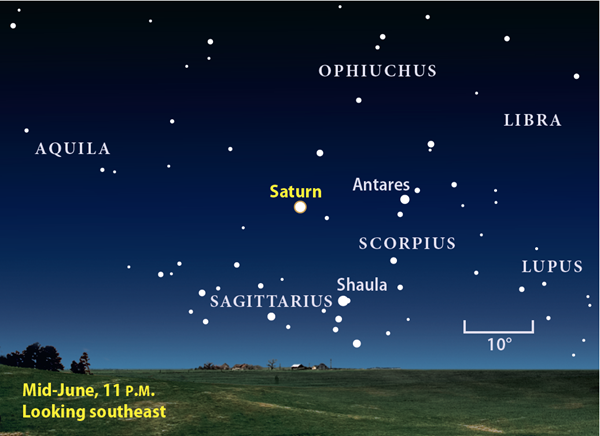

Saturn reaches opposition June 15, when it lies opposite the Sun in our sky and thus remains visible all night. The planet also comes closest to Earth at opposition, so it shines brightest and looms largest when viewed through a telescope. Although you can view the ringed planet any time of night, the best observing comes when it lies high in the south from late evening through early morning.

Saturn lies against the star fields of eastern Ophiuchus, just over the border from neighboring Sagittarius. Shining at magnitude 0.0 at opposition, the planet appears far brighter than any star in the surrounding constellations.

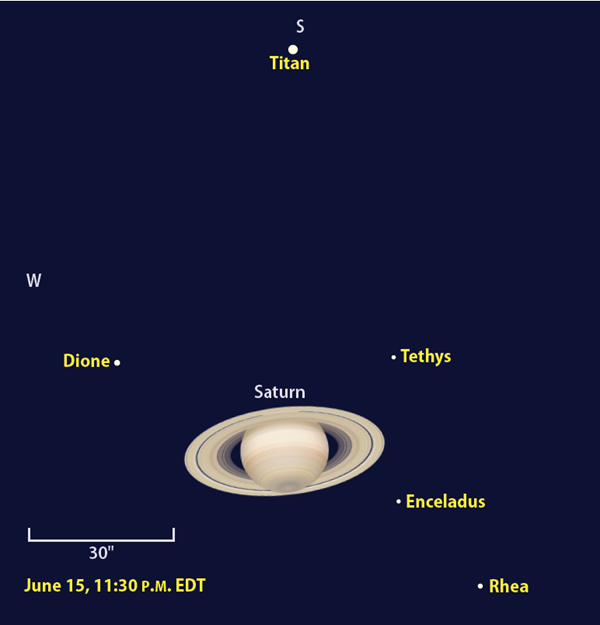

Several of these moons are in range of small telescopes. Giant Titan shines at 8th magnitude and appears as the brightest object near Saturn through any instrument. It orbits the planet in 16 days, passing north of the gas giant June 8 and 24 and south of it on the night of opposition, June 15/16. When Titan lies farthest east or west of the planet, it stands 3′ away.

Three 10th-magnitude moons lie less than half that distance from Saturn. Tethys, Dione, and Rhea all show up through 4-inch scopes. You’ll likely need an 8-inch instrument to see 12th-magnitude Enceladus. This active world — the Cassini probe discovered geysers erupting from its south pole — proves challenging because it orbits close to the glare of Saturn’s rings. You can pinpoint these five satellites on the night of opposition with the help of the chart above.

By the time Saturn climbs highest in the south, Neptune rises in the east along with the stars of Aquarius. Glowing at magnitude 7.9, it’s an easy binocular target in the southeastern sky an hour before twilight begins. Use the western side of the Great Square of Pegasus as a guide. Extend a line from Beta (β) to Alpha (α) Pegasi to the south about twice the distance between those stars and you’ll be in the planet’s vicinity.

Neptune lies roughly midway between 4th-magnitude Lambda (λ) and Phi (ϕ) Aquarii. Grab binoculars and locate 6th-magnitude 81 Aqr between them. Neptune lies about 15′ east of this star throughout June.

Uranus rises less than two hours after Neptune. In early June, this means near the end of twilight. Brilliant Venus stands near Uranus, however, and serves as a useful guide to finding the distant planet through binoculars. On the 1st, Uranus lies 2.4° northeast of Venus and appears in the same binocular field. As Venus wanders eastward, it passes 1.8° due south of Uranus on the 2nd and remains within 2° of the outer world through the 4th. Target Venus with your binoculars and imagine it as the center of a clock’s face. You’ll find Uranus just above the 9 o’clock position June 1, at 10 o’clock on the 2nd, at 11 o’clock on the 3rd, and at 12 o’clock on the 4th. You’ll need to look carefully to spot magnitude 5.9 Uranus, which glows some 10,000 times fainter than Venus.

Venus reaches greatest elongation June 3, when it lies 46° west of the Sun. The inner planet then rises two hours before our star and climbs more than 10° high in the east an hour before sunup. Venus shines at magnitude –4.4 and appears far brighter than any other morning object. The planet’s solar elongation shrinks by a couple of degrees during June, but by month’s end, it rises 2.5 hours before the Sun and stands 5° higher than it did early in the month. That’s because a line joining Venus and our star makes a steeper angle to the horizon as the month advances.

A majestic vista awaits observers on June 20 and 21, when a waning crescent Moon appears near Venus. Another photogenic scene arrives at month’s end. On the 30th, Venus stands 8° to the right of the Pleiades star cluster (M45). The two rise together in a dark sky. As morning twilight starts to paint the sky an hour later, the Hyades star cluster pokes above the horizon.

When viewed through a telescope June 1, Venus shows a 24″-diameter disk that appears slightly less than half-lit. As the planet moves away from us during the month, it shrinks in size while turning more of its sunlit hemisphere in our direction. On the 30th, the planet spans 18″ and shows a 62-percent-lit phase.

You might catch a glimpse of Mercury before dawn in early June. On the 1st, the innermost planet lies 4° high in the east-northeast a half-hour before sunrise. It shines brightly, however, at magnitude –0.4, and should show up through binoculars if you have an uncluttered horizon. Mercury disappears soon after as it heads toward superior conjunction June 21.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS | ||

| Evening Sky | Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mars (northwest) | Jupiter (southwest) | Mercury (east) |

| Jupiter (southwest) | Saturn (south) | Venus (east) |

| Saturn (southeast) | Saturn (southwest) | |

| Uranus (east) | ||

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

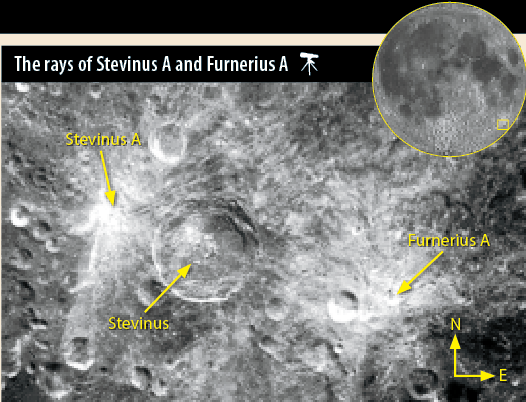

Few lunar features grab more attention near Full phase than the rayed crater Tycho. The impact that gouged out Tycho launched huge quantities of pulverized dust across the Moon’s nearside. This material lights up under the Sun’s overhead illumination around Full Moon. Because the impact happened quite recently in lunar history, its bright ejecta has not had time to darken under the weak but relentless sandblasting of particles blowing in the solar wind.

Although Tycho may be the brightest rayed crater, it’s not the only one. The most conspicuous features near the Full Moon’s southeastern limb are two smaller cousins: Stevinus A and Furnerius A.

Zoom in on the area between June 2 and 9 to separate the sources of these white rays. Stevinus A glows brighter than Furnerius A, which lies closer to the lunar limb. Yet Furnerius A is slightly larger — spanning 7.5 miles compared with its neighbor’s 5.1-mile diameter. The two straddle the modest 45-mile-wide crater Stevinus. Don’t expect to see Stevinus under the high Sun, however. Topographic features show up best when sunlight hits them at a shallow angle. It’s better to look for Stevinus during June’s final week.

If the Full Moon’s glare is too much for your eyes, try using a Moon filter. Other techniques for dimming the Moon include pumping up the scope’s power and putting on sunglasses.

Although no major meteor showers occur during June, it’s worth keeping an eye to the sky for sporadic meteors. These flashes of light arise when tiny dust particles enter Earth’s atmosphere and friction with the air vaporizes them. On a dark night, observers typically see a half-dozen or so of these sporadics per hour.

But this fine meteoritic dust also plays a role in creating summer’s beautiful noctilucent clouds. These highly reflective, silver-blue clouds develop in the coldest part of Earth’s atmosphere, about 50 miles above the surface, where ice crystals form on the dust particles. They appear most often in early summer from latitudes between 50° and 60° north. Look for them during twilight an hour or two after the Sun sets (or before the Sun rises), when our star still illuminates these high-flying clouds but the lower atmosphere is dark.

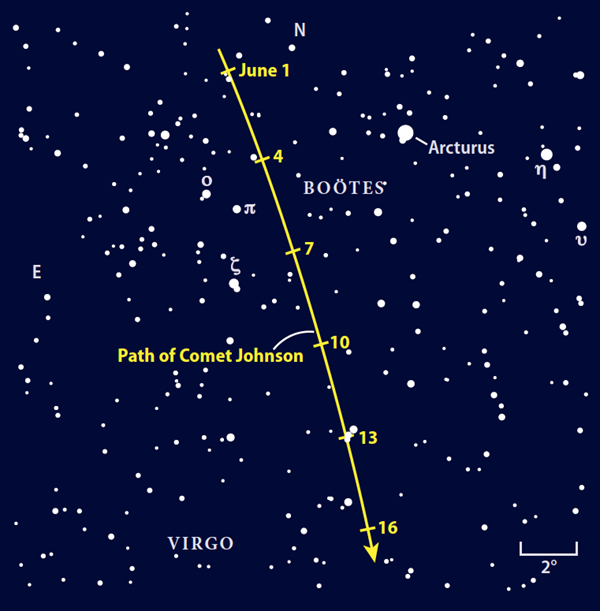

Our current comet cornucopia will last only a couple more months, so take advantage of it while you can. Comet Johnson (C/2015 V2) has been brightening for more than a year and should reach its peak in June. This first-time visitor to the inner solar system makes its closest approach to Earth on the 5th, one week before it passes closest to the Sun. And Johnson also remains visible all night. The 6th-magnitude object moves from Boötes into Virgo this month, passing east of magnitude 0.0 Arcturus on June 3 and 4.

Earth also swings from one side of the comet to the other. Imagine viewing a picture of a classic V-shaped comet taped to a window as you approach a door next to it. The comet transforms into an edge-on knife as you walk through the door and then returns to its V shape once you reach the other side. Comet Johnson appears edge-on May 30 and returns to normal two or three nights later.

Comet 41P/Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresak also stays out all night. Look for this 9th-magnitude object once the Moon exits the evening sky on the 11th. It’s then heading south along the eastern border of Ophiuchus. It skims west of the open star cluster NGC 6633 from June 12–14.

Comet PANSTARRS (C/2015 ER61) rounds out our comet trio. It should reach 7th magnitude in this month’s morning sky. The best views come in June’s first week as it speeds eastward against the backdrop of Pisces.

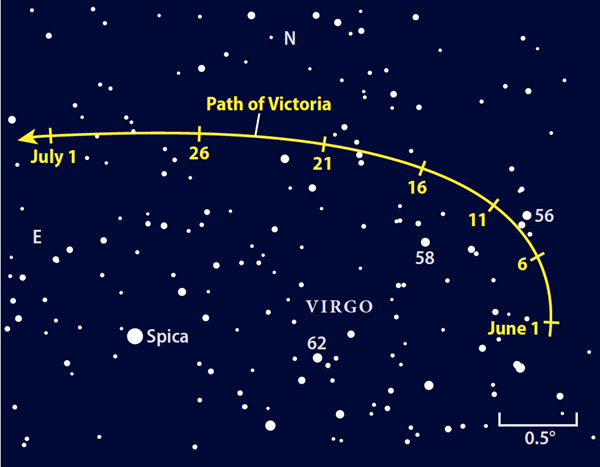

We usually feature bright asteroids because they tend to be easier to track against the starry background. But brighter is not always better. You’ll never get lost looking for 12 Victoria this month because it lies no more than 2.5° from 1st-magnitude Spica, Virgo’s blue-white luminary. This area lies high in the southwest once evening twilight fades away.

Still, you’ll need to pay close attention to the star patterns to identify this 70-mile-wide minor planet. Victoria dims from magnitude 10.5 to 11.0 this month, and lots of similarly bright stars populate its vicinity.

Use the chart below, which shows objects to magnitude 11.0, to home in on the right region. Your best strategy is to notice its movement from night to night against the background lights. Good times to try include June 7 and 8, when Victoria skims east of a triangle of stars that includes 56 Virginis, and June 18–20, when the asteroid slides through a crooked line of stars.

Sketch the field on one night and pencil in the point of light you think is Victoria. By the next night, you should be able to detect Victoria’s displacement and thus confirm its identity.