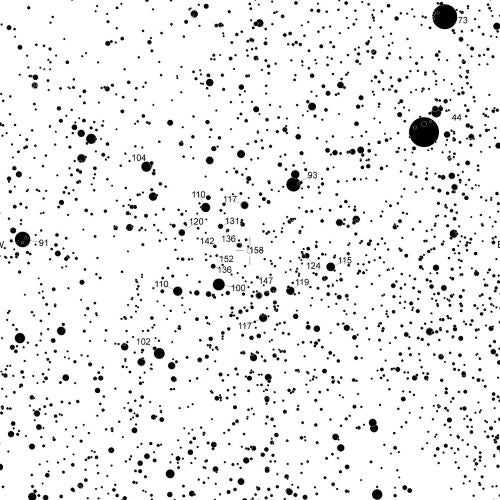

Aside from sky conditions, one’s ability to snag the central star requires seeing to at least magnitude 15 through your telescope. To find out how faint a star you can see, try using the American Association of Variable Star Observers’ star chart for HS Sagittae (bottom right) before heading for the Ring. This star lies about 17° southeast of M57 in the tiny constellation Sagitta the Arrow. Comparing the eyepiece view with this chart will reveal your scope’s limiting magnitude.

Seeing faint is only part of the equation, however. What’s paramount to success is your ability to overcome yet another obstacle: the feeble “mist” filling the Ring’s annulus. When seen at low magnification, the mist appears bright, thus lowering the contrast between the central star and its background. In 1988, several observers at the 18-inch f/14 Clark refractor at Wilder Observatory in Amherst, Massachusetts, couldn’t detect the Ring’s central star when viewed at 250x in a wide field of view because M57’s “hole” was filled with light. After they changed the magnification to 1,000x, however, the Ring filled the field of view and everyone saw the central star.

In August 1995, at Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton in California, the Ring’s inner edge rimmed the small field of view of the 36-inch f/19 Clark refractor at 1,176x. The sight of its dark well revealed the central star and another field star shining brightly against a dark, high-contrast background. An immediate walk down the hall to Lick’s 40-inch Nickel reflecting telescope and a glance at the Ring through it at a much lower power showed a magnificently bright ring filled with a luminous mist. The central star, however, was invisible despite the increase in aperture.

The smallest telescope through which I’ve seen the Ring’s central star is the 9-inch f/12 Clark refractor at Harvard College Observatory in 1976, and the story was no different. Seeing the star required magnifications between 600x and 700x with the Ring nearly filling the field of view. Much time and patience behind the eyepiece were also required — two other important factors needed to achieve success when using smaller apertures.

A final consideration is the eye’s sensitivity to color. Observers with blue-sensitive eyes have a better chance of seeing the Ring’s hot central star than those with red-sensitive eyes. Young stargazers — and people who have had cataracts removed — have a much better chance at achieving success than more senior observers whose eye lenses have begun to yellow.