Although you’d never know from looking at it casually, Deneb is one of the most luminous stars in the entire sky. Even though it appears fainter than Vega and Altair, Deneb actually emits much more energy than either.

So, why is Deneb fainter? It’s simply a matter of distance. Altair lies 17 light-years away. Vega is not much more distant at 25 light-years. Deneb, however, lies nearly 1,500 light-years away. Were it as close to us as Altair, Deneb would shine as brightly as the Quarter Moon. Wow!

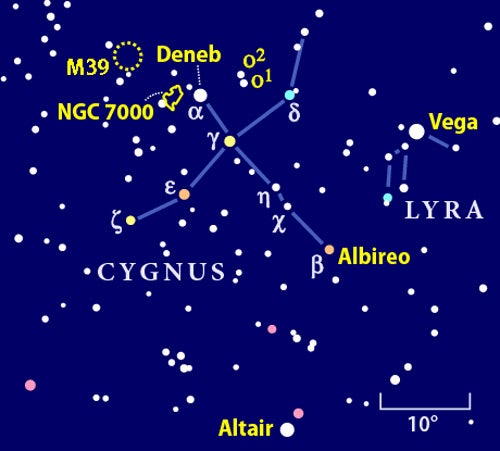

Cygnus marks one of my favorite binocular playgrounds. Even from my moderately light-polluted suburban backyard, I can sit back on a chaise lounge, peer through my modest 10×50 binoculars, and trace the gentle glow of the Milky Way from Deneb southward to the star Albireo, which marks the bird’s beak.

Small telescopes reveal Albireo’s true identity as a showpiece double star with a 3rd-magnitude golden primary star accompanied by a 5th-magnitude sapphire-blue companion. Their colors don’t show up as well, but both stars can be spotted through steadily held 10×50 binoculars.

If double stars interest you, then stop by Omicron (ο) Cygni, one of the sky’s finest objects through binoculars. Look for it 5° — or about two-thirds of a binocular field — northwest of Deneb. The Omicron system is another colorful pair, with a 4th-magnitude orange star accompanied by a 5th-magnitude bluish sun. Their colors stand out even in their rich neighborhood.

Up for a couple of challenges? Good. Let’s begin with the open star cluster M39 (NGC 7092), found along the lane of the Milky Way about 9°, or approximately 1.5 binocular fields, northeast of Deneb.

To find it, scan from Deneb to a small arrowhead of stars just to the northeast. Follow the arrowhead’s aim to a string of six faint stars that continues to the east-northeast. M39 lies to the east of the sixth (easternmost) star in that line. Through most binoculars, M39 will look like a tiny, triangular grouping of about two-dozen faint points. Whenever I am fortunate enough to view from a dark location, M39 appears suspended in front of a blanket of faint stardust.

Let’s finish with the North America Nebula (NGC 7000). Although spotting this celestial continent is tough, it is actually easier to see through binoculars, or even with the naked eye, than through the narrow fields of most telescopes. Still, you’ll need dark, perfectly clear skies, a steady hand, and sharp eyes to make it out. Take aim at Deneb, and then look about 3°, or half a binocular field, to its east.

No luck? Here’s a hint. Look for the “East Coast,” from the Carolinas to Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. These are the easiest parts of the nebula to see thanks to the darkness of the “Atlantic Ocean” formed by a separate dark nebula silhouetted in the foreground. The “West Coast” is much more difficult to distinguish.

Even though the North America Nebula photographs beautifully, we can never see its distinctive red color no matter how hard we try. Our eyes’ color blindness in dim light reduces it to a faint grayish glow.

Tom Strobel, from White Bear Township, Minnesota, asks how to hold binoculars steadily. Grasp the barrels around the objective lenses, cradling them with your forefingers and thumbs. This seems to work best, although I prefer putting binoculars on a tall photographic tripod or, better still, a parallelogram mount. A separate support also makes it easier to go back and forth between binoculars and star maps.

Cygnus holds so many beautiful star fields, it’s easy to spend the evening casually scanning the sky through binoculars. Next month, we’ll pay a royal visit to the queen of the fall sky. Till then, remember: Two eyes are better than one.