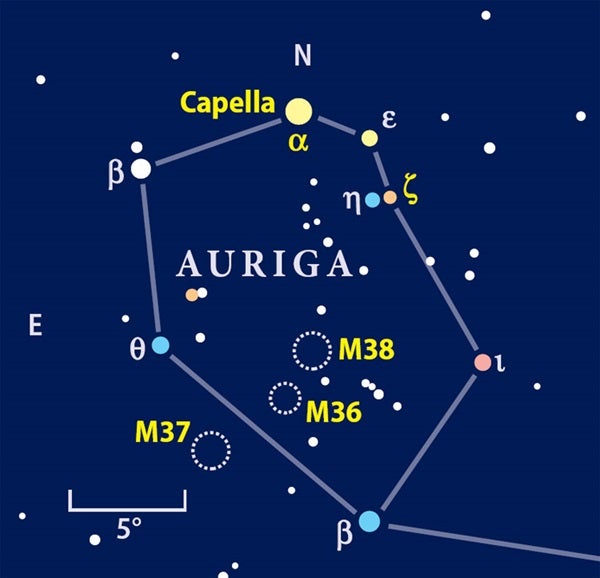

Just south of Capella lie three 3rd-magnitude stars in the shape of an isosceles triangle. Often referred to as “The Kids,” this trio represents two young goats held by Auriga. They glisten beautifully through binoculars. Two shine pure white, while the third, Zeta (ζ) Aurigae, appears orange.

Hop a little more than a binocular field south of, or below, the triangle to see a neat little pattern of five faint stars. Four form a parallelogram, while the fifth lies just below. This isn’t a star cluster, but an asterism — one of those fun shapes you bump into every now and again.

Given March’s windy days, the pattern reminds me of a box kite with a tail being whipped about. With your unaided eyes from a dark site, you might see the kite’s oblong glow slightly west of the constellation’s center.

While looking for M38, you might notice M36, a second fuzzy glow snuggled between two faint field stars about half a binocular field to the east. M36 is smaller and more condensed than M38, so you should be able to spot it more easily. If you have good eyes and 70mm or larger binoculars, you might see a few faint stars peering back at you. Telescopes reveal that the cluster’s brightest stars fall into a pattern resembling a crooked Y.

The third and brightest Messier open cluster in Auriga, M37, rests about a binocular field east of M36. Because its brightest stars shine at only 9th magnitude, M37 appears as a faint, misty patch of light through binoculars.

March is traditionally the best month to spot all 109 Messier objects in a single dusk-to-dawn observing session. The Sun’s position in the sky around the vernal equinox March 20 leaves all but M30 in view sometime during the night. This year, the Moon stays out of the way the weekend of March 25, so that’s prime time.

Astronomy columnist Glenn Chaple has challenged me the last few years to run the marathon against him. He knows he can’t win, but clouds have let him save face. You’ll have nowhere to hide this year, Chaple! I’m ready for you, armed with my trusty 10×50 and 16×70 binoculars.

My best binocular marathons were 85 objects through a pair of 7x35s in the 1980s and 101 through 11x80s some years later. How about you, dear reader? Care to join us? E-mail me at the marathon to let me know how you made out. I’ll publish the best binocular tallies in a future column.

Next month, we celebrate spring by visiting two of the season’s finest binocular star clusters. Till then, remember: Two eyes are better than one!