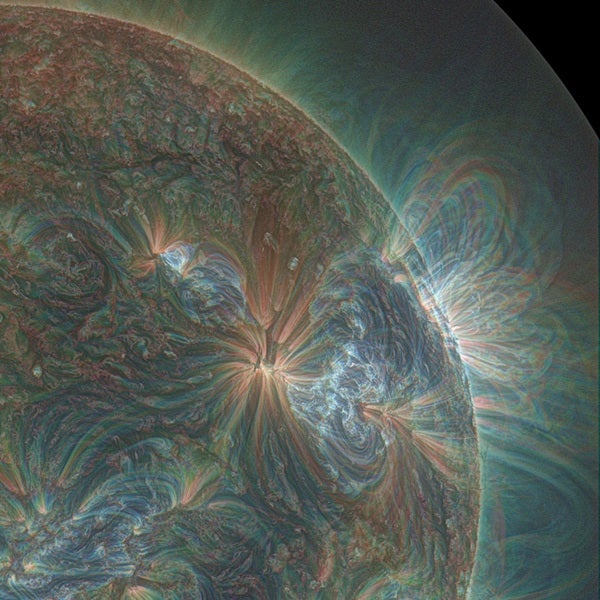

The Sun’s outermost atmosphere, the corona, is made of magnetized solar material, called plasma, that has a temperature of millions of degrees and extends millions of miles into space. On January 17, the joint European Space Agency and NASA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft observed puffs emanating from the base of the corona and rapidly exploding outward into interplanetary space. The puffs occurred roughly once every three hours. After about 12 hours, a much larger eruption of material began, apparently eased out by the smaller-scale explosions.

By looking at high-resolution images taken by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) and NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) over the same time period and in different wavelengths, Nathalia Alzate from the University of Aberystwyth in Wales and her colleagues could focus on the cause of the puffs and the interaction between the small- and large-scale eruptions.

“Looking at the corona in extreme ultraviolet light, we see the source of the puffs is a series of energetic jets and related flares,” said Alzate. “The jets are localized, catastrophic releases of energy that spew material out from the Sun into space. These rapid changes in the magnetic field cause flares, which release a huge amount of energy in a very short time in the form of super-heated plasma, high-energy radiation, and radio bursts. The big, slow structure is reluctant to erupt and does not begin to smoothly propagate outwards until several jets have occurred.”

Because multiple spacecraft observed the events, each viewing the Sun from a different perspective, Alzate and her colleagues were able to resolve the 3-D configuration of the eruptions. This allowed them to estimate the forces acting on the slow eruption and discuss possible mechanisms for the interaction between the slow and fast phenomena.

“We still need to understand whether there are shock waves formed by the jets passing through and driving the slow eruption,” said Alzate. “Or whether magnetic reconfiguration is driving the jets allowing the larger, slow structure to slowly erupt. Thanks to recent advances in observation and in image-processing techniques, we can throw light on the way jets can lead to small and fast, or large and slow, eruptions from the Sun.”