In 2022, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) unveiled its first set of science images. Since then, JWST’s releases have continued to dazzle astronomers and the public alike, revealing stunning views of some of the darkest and most exciting places in the universe.

NASA’s new telescope is allowing us to see light from the universe in ways we never have been able to before. The JWST Deep Field, reminiscent of the groundbreaking Hubble Deep Field taken in 1995, shows thousands of distant galaxies. Almost every fleck of light is a faint object in the early universe.

Seeing in infrared

JWST is an infrared telescope, meaning that it observes a different wavelength of light than what our human eyes have evolved to see. Because infrared light is largely blocked by Earth’s atmosphere, JWST’s residence in space means it can view light that ground-based telescopes on Earth simply can’t detect. And because cosmic dust is largely transparent to infrared light, swaths of space that were otherwise obscured by dust are now open to astronomers.

Since it began operation, the JWST team has been busy pointing the telescope at myriad targets. There’s even a fun Twitter page (@JWSTObservation) you can follow with live updates about where the telescope is pointing, the exposure time, the instrument currently being used, and more.

Observe JWST’s first targets

In celebration of all the wonderful data and images that JWST will continue to deliver, I recommend running your own Webb mini-marathon to explore some of the objects the space telescope has captured. These targets are all within reach of a small backyard telescope (some even with a pair of binoculars) and have been chosen for observers in the Northern Hemisphere above a latitude of about 30°. Ideal times to view these objects run from early fall through winter.

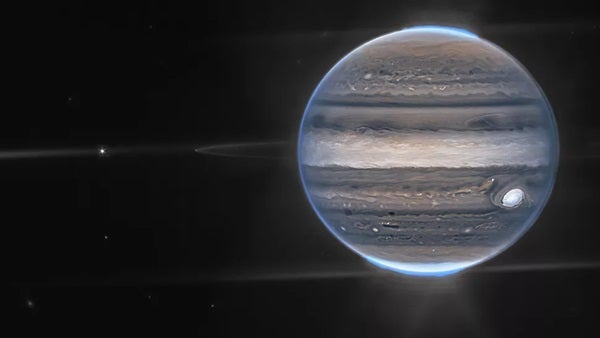

Starting in our own solar system, JWST has revealed breathtaking images of Jupiter. So begin your Webb mini-marathon by pointing your scope toward the gas giant, which sets around 11 P.M. local daylight time in mid-September and 3:30 A.M. local time in mid-December. Jove is a bright point of light in the dim constellation Aries, making it relatively easy to find. And if you target Jupiter while it’s still well above the horizon, you’ll have a good shot at spotting all four Galilean moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — through your scope. In total, Jupiter has 95 moons. Any small scope will show the Galilean satellites; a much larger scope might yield a few more moons as small pinpricks of light.

JWST also used its Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) to capture incredible shots of Neptune, including the planet’s turbulent atmosphere and ethereal ring system. In the image, Neptune’s moon Triton outshines the planet because Neptune’s atmosphere is rich in methane gas, which absorbs light at the wavelengths JWST is sensitive to.

Currently, Neptune is near Jupiter in the night sky. To find Neptune, start at Jupiter and move west (down and slightly to the right) toward Pisces and Aquarius. Neptune is not visible to the naked eye, so you will need binoculars or a telescope to find it. You may want to check planetarium software or our website’s observing section to determine the exact location of the faint planet when you plan to seek it out.

Next, as a last look at one of the most dazzling summer nebulae in the Milky Way, JWST has imaged the Pillars of Creation, which lies inside the Eagle Nebula (M16) in the constellation Serpens. You’ll want to look for this one earlier in the evening, before it sets. To find the soaring nebula, locate the star Gamma [𝛾] Scuti in the constellation Scutum, right next to Sagittarius. Point your telescope at this star and move slightly up and to the right (about 3° northwest) to the land on M16. Through a small telescope, the Eagle Nebula will appear to be a faint, grayish-green smudge of light. The famous Pillars of Creation will be small dark shadows within the misty light of the nebula.

If you are up for another challenge and have a medium-sized telescope, you can search for Stephan’s Quintet. This time, start at Pegasus, focusing on the bright star Scheat (Beta [β] Pegasi). Move one star northeast of Scheat to Matar (Eta [η] Pegasi). From there, move about the same distance upward and slightly to the right to find this faint group of galaxies. This object was one of the first images released from JWST. One thing that I like to do when challenging myself with fainter objects is to look at a detailed photograph of the object first — that way my mind already knows what to roughly look for in the night sky. I find that I am able to recognize an object faster using this technique.

As JWST points to more targets, you can add to this list and customize it to be as challenging or as relaxing as you want!