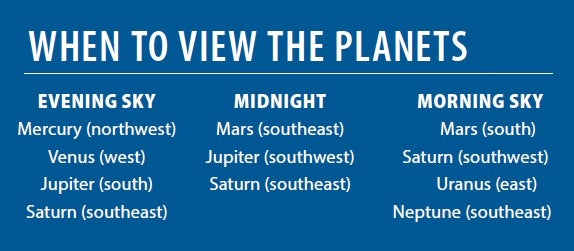

Our great run of spring and summer planets continues this month as Saturn comes to opposition and peak visibility. Meanwhile Jupiter, a month past its own opposition, lights up the sky from evening twilight until the wee hours. And Mars, which will reach opposition in July, stands out from late evening until dawn.

But the planetary delights begin with splendid appearances by the two inner planets shortly after sunset. We’ll start our tour with innermost Mercury as it climbs into view after midmonth.

Your first good chance to spot this world comes June 19. Scan the area above your west-northwestern horizon starting 30 minutes after sunset. Mercury lies 7° high and should be fairly easy to spot in the twilight with your naked eyes, because it shines brightly at magnitude –0.8. That same evening, the planet forms a skinny triangle with Gemini’s twins, Castor and Pollux. These bright stars stand side by side 10° above Mercury.

As the month progresses, Mercury’s visibility improves as it climbs away from the Sun. Its ascent coincides with Gemini’s descent, and on June 27, the planet sits in line with Castor and Pollux. Mercury (now at magnitude –0.3) appears on the left with Pollux 7° to its right and Castor 4.5° beyond it. The trio stands 10° high a half-hour after sundown.

Mercury typically appears as a blurry disk through a telescope because its light has to pass through a lot of Earth’s turbulent atmosphere. On June 19, the planet spans 5.6″ and shows an 81-percent-lit phase. By the 27th, it appears 6.3″ across and 66 percent illuminated.

As you gaze at Mercury, you no doubt will notice a much brighter object higher in the west. Venus brightens from magnitude –3.9 to –4.1 during June and is by far the brightest point of light in the sky. As the month opens, the dazzling object lies in central Gemini 9° below Pollux. By June 11, it stands 6° to the left of this 1st-magnitude star.

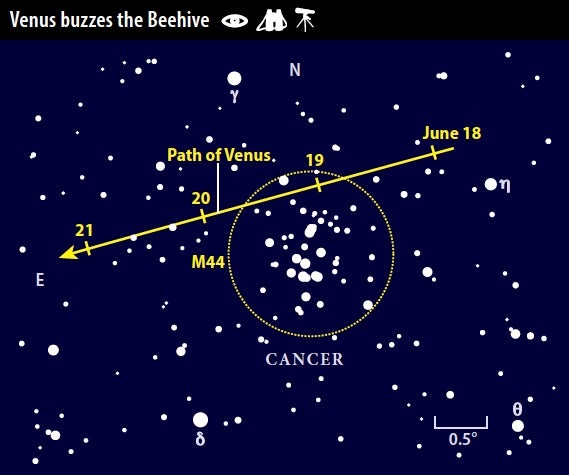

Venus skirts the northern edge of M44 on the 19th, passing just 44′ from the cluster’s center. This presents a golden photo opportunity. The stunning jewels of the Beehive are a favorite target for astroimagers, and Venus’ brilliant light adds a nice touch.

The planet continues eastward through the rest of June, crossing into Leo on the 29th and ending the month 10° shy of the Lion’s brightest star, 1st-magnitude Regulus. Surprisingly, Venus hangs a bit lower in the evening sky as June wraps up. It stood 16° high an hour after sunset in early June, but its altitude drops to 15° by month’s end. And by the time it reaches greatest elongation from the Sun in mid-August, it will appear only half as high. Blame the ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun and planets across the sky — which makes a steeper angle to the western horizon after sunset in spring.

Your best telescopic views of Venus come in twilight because the planet’s glare is almost overwhelming in a dark sky. On June 1, it appears 13″ across and 80 percent lit. By the 30th, the planet spans 16″ and the Sun illuminates 70 percent of its disk.

Despite the inner planets’ charms, June belongs to the solar system’s outer worlds. Jupiter rides high in the south at dusk, a brilliant object set against the backdrop of Libra the Scales. It shines at magnitude –2.5 in early June and fades only to magnitude –2.3 by month’s end.

The giant planet reached opposition and peak visibility in early May, and it spends June moving slowly westward relative to the background stars. It begins the month 0.9° north-northeast of Zubenelgenubi (Alpha [α] Librae) and ends the month 2° northwest of this 3rd-magnitude star.

Although Jupiter’s diameter shrinks from 44″ to 41″ during June, that’s big enough to show nice detail through any telescope. Begin observing in early evening when the gas giant stands high in the south and its light passes through less of Earth’s atmosphere.

The planet’s four Galilean moons also show up clearly through small scopes. Be ready to observe an intriguing event the night of June 7/8. Ganymede lies in Jupiter’s shadow in early evening but gradually returns to view between Io and Callisto. At 12:40 a.m. EDT, Io and Callisto appear 25″ apart southeast of the planet. If you watch the space between these moons, you’ll see Ganymede emerge into sunlight starting at 12:43 a.m. It returns to full visibility by 1:02 a.m.

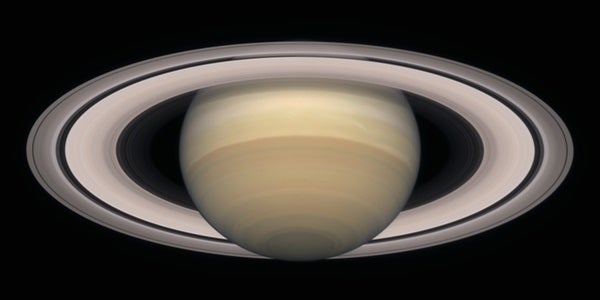

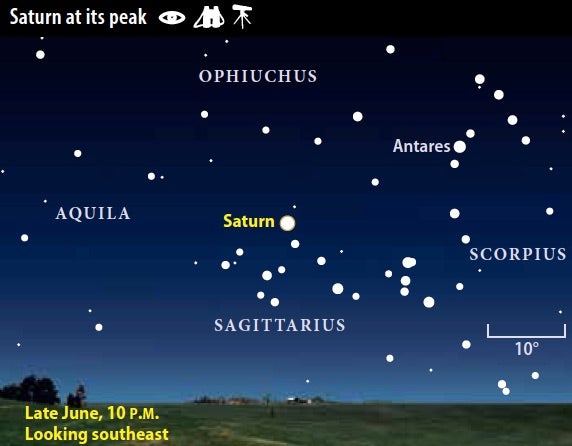

Saturn rises shortly after 10 p.m. local daylight time in early June, but your best views will come around the time it reaches opposition June 27. It then lies opposite the Sun in our sky and remains visible all night. It also shines brightest at opposition, cresting at magnitude 0.0.

Saturn lies among the background stars of Sagittarius. Binoculars reveal several outstanding deep-sky objects in its vicinity. On June 1, the planet stands 1.9° northwest of the 5th-magnitude globular star cluster M22 and 3.2° south of the similarly bright open cluster M25. The Lagoon and Trifid nebulae (M8 and M20, respectively) lie 7° west of Saturn. By month’s end, Saturn’s westward motion brings it about halfway between M25 and M8. Unfortunately, a Full Moon lies within 2° of Saturn on opposition night and ruins the binocular view.

Of course, nothing really detracts from the view of Saturn through a telescope. At opposition, the planet’s equatorial diameter extends 18.4″ while the rings span 41.7″ and tilt 26° to our line of sight. Saturn is only 1 percent smaller in early June, so its appearance hardly changes this month. Look for the Cassini Division that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring. An 8-inch scope shows the narrow Encke Gap near the A ring’s outer edge.

Saturn’s brightest moon, 8th-magnitude Titan, shows up through any telescope. A 4-inch instrument also reveals Tethys, Dione, and Rhea closer to the planet.

If you observe Mars all month, you can’t help but notice rapid changes in its appearance as it approaches a spectacular late July opposition. Mars more than doubles in brightness during June, climbing from magnitude –1.2 to –2.1. And the improvement visible through a telescope is no less striking — the planet’s diameter grows 35 percent, from 15.3″ to 20.7″. At its peak in late July, Mars will gleam at magnitude –2.8 and will swell to 24.3″ across.

From its position in southern Capricornus, Mars remains low in the sky for Northern Hemisphere observers. The best telescopic views come when it climbs highest in the hours before dawn. The ruddy world rotates on its axis once every 24.6 hours, so the hemisphere we see changes slowly from night to night. Oddly enough, the planet’s darkest feature, Syrtis Major, lies near the same longitude as its most prominent bright feature, Hellas. From North America, both lie near the center of Mars’ disk on mornings from about June 6–10.

The two outermost planets appear best before dawn. Neptune rises around 2 a.m. local daylight time in early June and two hours earlier by month’s end. Look for it in the southeast among the background stars of eastern Aquarius just before twilight starts to paint the sky. It glows at magnitude 7.9 and shows up through binoculars just 1° west-southwest of magnitude 4.2 Phi (ϕ) Aquarii. A telescope reveals its 2.3″-diameter disk and subtle blue-gray color.

You’ll want to wait until late June to view Uranus. It then stands 20° high in the east as twilight begins. The ice giant resides in the southwestern corner of Aries, 12° south of the Ram’s brightest star, magnitude 2.0 Hamal (Alpha Arietis). Uranus shines at magnitude 5.9 and is an easy binocular object, though a handful of similarly bright stars may confuse you. To identify the planet, point a telescope at your suspected target. Only Uranus will show a blue-green color on a disk that measures 3.4″ across.

As the solstice approaches, the waxing crescent Moon appears higher each evening. Different wonders pop into view along the terminator that separates day from night as it advances westward across Luna’s face.

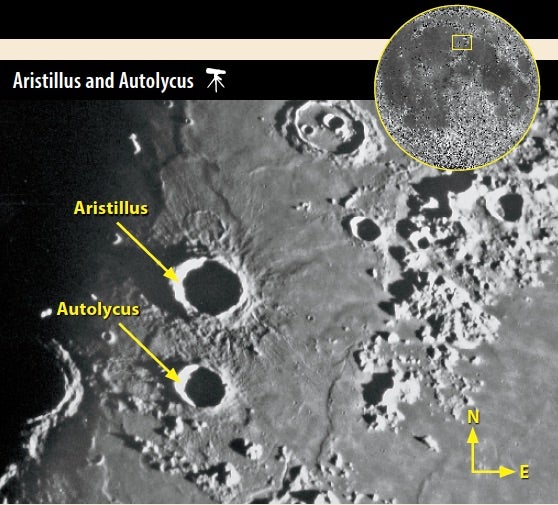

By First Quarter Moon on June 20, our satellite rides halfway up the sky during twilight. Look for the rugged lunar Apennines thrusting diagonally into the sunlit domain north of the equator. In the plains along the terminator a bit north of these mountains lie two striking young craters: Autolycus and Aristillus. They formed a couple of billion years ago, after the Late Heavy Bombardment finished pummeling the solar system’s inner worlds.

The low Sun angle at First Quarter highlights the debris aprons that splattered from these impact sites. The larger impactor that created Aristillus excavated a lot more material — notice the many streaks and ridges that radiate from this crater. Both craters’ high walls prevent sunlight from reaching their central peaks and floors. If you return June 21, the higher Sun reveals Aristillus’ multiple central peaks, but begins to conceal its apron’s roughness.

Compare the characteristics of these “youthful” scars with the much larger and older impact craters Hipparchus and Albategnius along the terminator just south of the lunar equator. Their degraded features, the result of incessant pounding from smaller impacts over time, attest to their greater age. Their central peaks are lower, their walls are rounded and pockmarked with dozens of smaller craters, and their debris aprons are smoothed out.

June offers no major meteor showers, but keep watch for the few minor ones as well as the normal flow of sporadic meteors. Perhaps the best minor shower radiates from the constellation Ophiuchus and peaks the morning of June 20. The Ophiuchids could deliver up to 5 meteors per hour after the First Quarter Moon sets around 1 a.m. local daylight time.

Meteors arise when dust particles slam into Earth’s atmosphere and burn up through friction. Similar dust helps create gorgeous noctilucent (night-glowing) clouds. These silver-blue clouds form when ice crystals freeze onto dust particles about 50 miles above Earth’s surface, some five to 10 times higher than cirrus clouds. They occur most often in early summer from latitudes between 50° and 60°. Look for them during twilight an hour or two after the Sun sets (or before the Sun rises).

Several periodic comets are slated to cross our summer and fall skies. The best of the lot should be Comet 46P/Wirtanen, which may be visible to the naked eye in late fall and early winter.

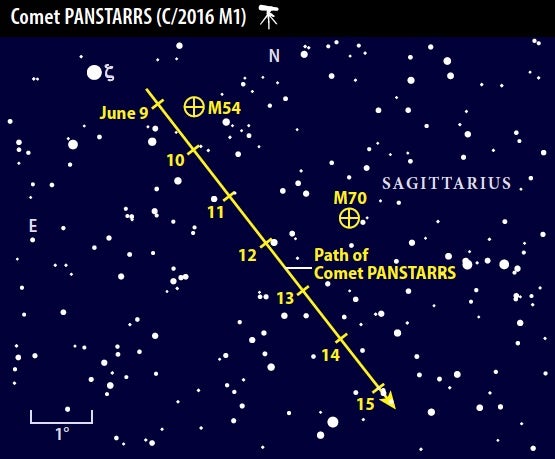

But plan to set your sights on Comet PANSTARRS (C/2016 M1) this month. The 10th-magnitude object passes through the bottom of Sagittarius’ Teapot asterism in June’s second week. On the 9th and 10th, it slides about 40′ from the 8th-magnitude globular star cluster M54. A few nights later, it passes twice as far from the similarly bright globular M70. The waning crescent Moon doesn’t rise until 3 a.m. local daylight time on the 9th and about a half-hour later each succeeding night, so it won’t hinder your quest.

You’ll want to observe between 2 and 3 a.m., when Sagittarius climbs highest in the south. And you’ll probably need a 6-inch or larger telescope and a dark observing site to see it. The light from PANSTARRS likely will spread out enough to render it invisible at low power. Crank the magnification up to 100x or so to pull it out of the background. And if conditions allow, don’t hesitate to add more power.

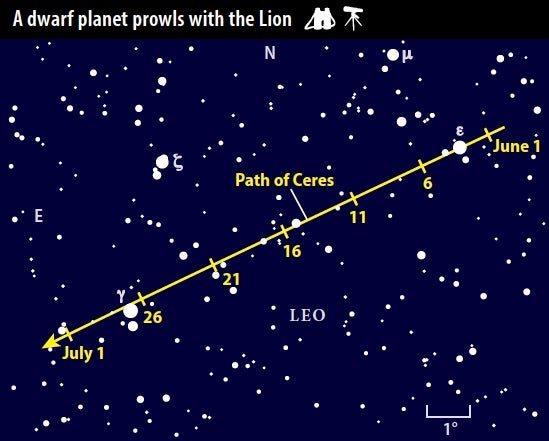

If you look to the west as darkness falls this month, you can’t help but see brilliant Venus. Above it lurks the familiar shape of Leo the Lion, current home to a much fainter solar system relative, the dwarf planet Ceres.

To find Ceres, first locate Leo’s Sickle asterism. (Many people see this shape as a backward question mark.) First-magnitude Regulus marks the bottom of this asterism, but your guide stars to Ceres lie a short distance north in the curved section. Pinpoint 2nd-magnitude Gamma (γ) Leonis, a lovely double star, and 3rd-magnitude Epsilon (ε) Leo, the Sickle’s end point, and you’re but a short hop from identifying the dwarf planet.

The map below points the way on any night this month, but June 3, 15, and 27 stand out because 9th-magnitude Ceres then passes within 0.1° of prominent background stars. It’s near Epsilon on the 3rd, a 6th-magnitude sun on the 15th, and Gamma on the 27th. On each of those evenings, the dwarf planet’s motion should be obvious within an hour.