This year has been a great one for comets, and it’s not over yet. Comet C/2023 H2 (Lemmon) is passing close to Earth at the end of this week, offering a bright binocular or small-scope target you can enjoy nearly all evening long.

Discovered in April this year, Comet Lemmon passed perihelion, the closest point to the Sun in its orbit, on October 29 at a distance of roughly 0.9 astronomical unit, just inside Earth’s orbit. (One astronomical unit, or AU, is the average distance between Earth and the Sun.) Now on its way back to the outer solar system, it’s passing closest to Earth on Friday, November 10. At its closest, the comet will be some 0.19 astronomical unit from our planet, or nearly 18 million miles (29 million kilometers) away.

Don’t worry — that’s 75 times farther than the Moon. Still, it’s pretty close for a comet, and Lemmon will appear brightest for the next few days before rapidly fading.

The comet was last recorded at 6th magnitude, bright enough to see easily with binoculars (the larger the better) or a small telescope. It’s likely to stay this bright, perhaps even reaching 5th magnitude, through the weekend, making it a ready target for Northern Hemisphere observers and astrophotographers. Lemmon is not currently visible in the Southern Hemisphere; it will be soon, though it will be fading.

How to see Comet Lemmon

Comet Lemmon is now visible for several hours after sunset, so you don’t need to rush outside to try to catch it in the bright twilight, as with other recent bright comets. This comet is visible soon after sunset and remains in the sky for several hours, setting around 10:30 P.M. local time. As with all astronomical observations, you’ll want to look for it earlier rather than later, as the closer to the horizon it gets, the more distorted its image will become as you look through more of Earth’s atmosphere (which is also more turbulent near the ground).

And perhaps the best part? The Moon is not currently visible in the evening sky, which means the sky is darker and the comet will be easier to pick out. Still, you’ll want to get to as dark a site as possible for a better view, though even suburban comet-hunters can pick this one up.

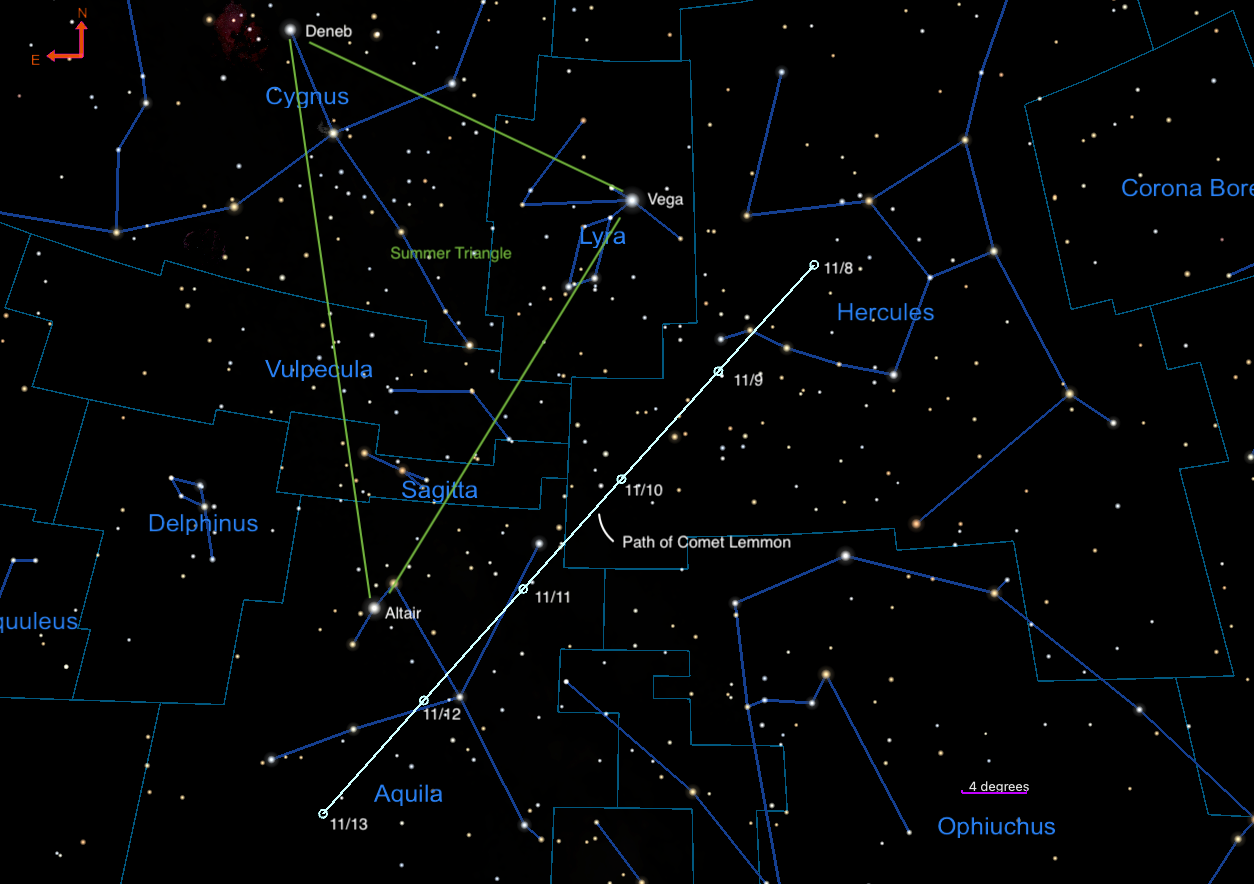

To find Comet Lemmon, look west after sunset. Specifically, look for three bright stars that form a large triangle — this is the Summer Triangle, which sits overhead in the summer and is now sinking lower in the west as fall slowly turns toward winter. The brightest star in this triangle is also currently the lowest in the sky — that’s Vega in the constellation Lyra. Through November 10, Comet Lemmon is moving through Hercules, which lies just below Lyra in the sky as they set. After that, Lemmon will move through Aquila to the southeast, passing due south of the bright star Altair (the second-lowest point in the Summer Triangle) on the 12th.

Because Lemmon is so close to Earth, it’s moving through the sky quickly, covering roughly ¼° per hour! The comet is moving southeast, or to the left and upward slightly night by night (as seen from Earth, not the celestial sphere, more on that in a second). The chart below shows Lemmon’s position for the next few nights at 7 P.M. EST, so you may need to make slight adjustments depending on when you look for it. Note that this chart shows the sky in “celestial” coordinates with north up and east to the left; the view from the ground is slightly different (shown on the second chart below). If you’re using a telescope, note that your optics may rotate or even flip the image you see compared with the one below.

On the 10th, the easiest way to find Lemmon will be to first locate Vega and Altair, and draw a line between them. Lemmon will lie just below the rough midpoint of that line (again, at 7 P.M. EST). The chart below shows the position of the stars and Comet Lemmon at 6 P.M. local time from the Midwest, which is 7 P.M. EST (so the position matches that on the celestial chart above). The stars will be in this position around 6 P.M. local time from any location, though Lemmon may be slightly right or left of this position, depending on your location and time zone.

What will Comet Lemmon look like?

To the eye, comets typically look like small, white fuzzballs. This “fuzz” is the comet’s coma, a cloud of dust and gas surrounding the rock-ice nucleus. When the comet is in the inner solar system, the relatively balmy temperatures cause ices on or just below the surface to sublimate, or turn directly from a solid to a gas. This creates the coma as well as the tail.

For comets of Lemmon’s magnitude, a tail may be very faintly visible to the eye through your optics and should readily appear in astrophotos. Also visible in astrophotographs is the comet’s typical green glow, which comes from diatomic carbon in the nucleus.

If you can, get outside to view the comet this week or weekend. Not only will Lemmon fade quickly after its pass, it won’t be back anytime soon. The comet’s period is well over 3,000 years, so it’s got a long way to go before it makes another close pass of the Sun or Earth. So, as with all comets, it’s best to catch it while you can!