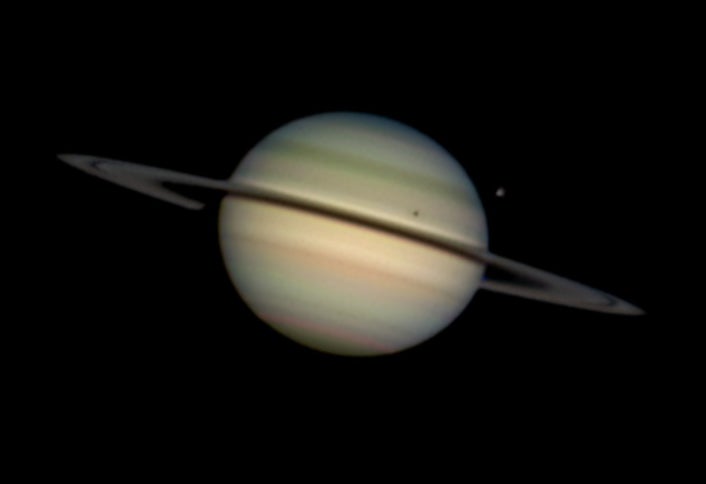

At public stargazes and evenings with friends at the telescope, we love to set our eyes on the wonders of Saturn and Jupiter at every opportunity. Year-round, whenever they’re above the horizon, they never cease to amaze. Mars, on the other hand, is easy to underappreciate because it appears small for much of the year, making it hard to pick out the kind of detail you can see on the gas giants.

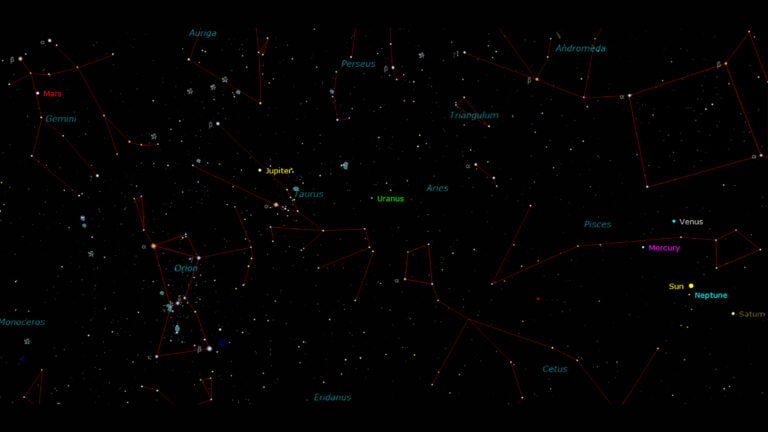

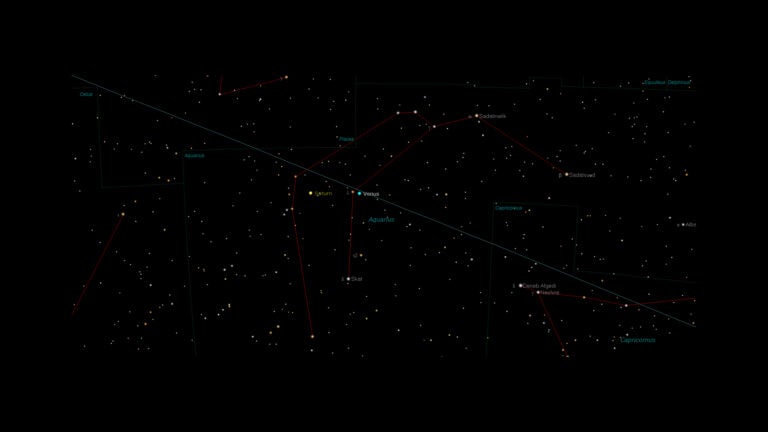

But every 26 months, the orbits of Earth and Mars allow us a closer look at the Red Planet when Mars is at opposition — which will happen on the night of Jan. 15 this year. In the early evening, Mars will be easy to locate: It will be the bright, ruddy, starlike object just below Castor and Pollux, the twin stars of Gemini, almost due east. It rises quickly and will be nearly overhead at midnight for the southern U.S., and still high for the rest of the country.

While you can see Mars as a tiny disk through binoculars, a telescope is necessary for garnering any detail. When it comes to planets, long-focal-length instruments are your friend — my favorite for viewing planets is my Celestron 8-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain, clocking in at 2,032 mm focal length. How much magnification you can throw at Mars will depend strongly on your local seeing conditions — that is, the steadiness of the atmosphere. If the seeing is good, go for your highest magnification eyepieces or use a Barlow lens with a lower power.

For nights of average seeing, a good rule of thumb is to use a magnification between 30x and 50x times the aperture of your telescope in inches. For example, with my 8-inch scope, 240-400x should work nicely, which means I’ll use 5mm to 8.5mm eyepieces. A humble Plössl — not the most complex of eyepiece designs — can deliver satisfying views. Give some color filters a try as well, if you have them, to bring out different features. Just don’t expect to see color.

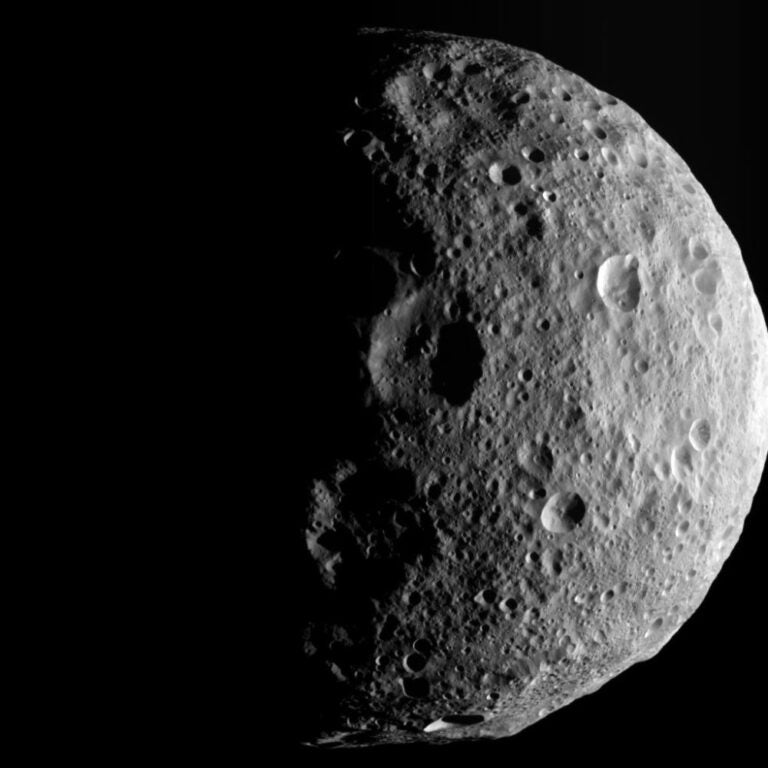

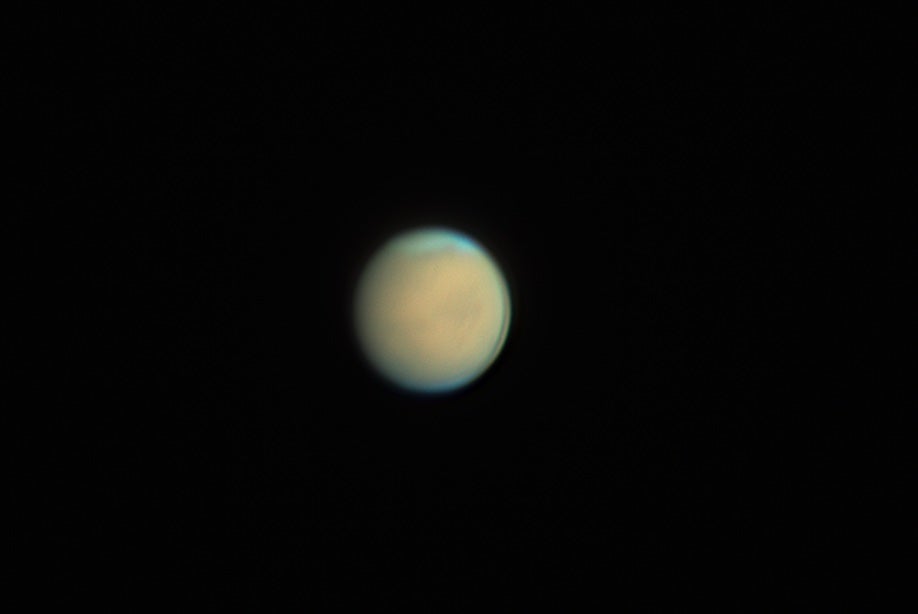

When observing Mars, there are three main features that are immediately evident: light-red dusty regions, darker areas of exposed volcanic rock, and the white polar ice caps. Early astronomers named the lighter regions like land masses, such as Elysium Planitia (the Elysium Plain), and named the darker regions like bodies of water, such as Mare Tyrrhenum (named for the Tyrrhenian Sea in the Mediterranean). The polar ice caps wax and wane with the martian seasons, and our ability to see them is also affected by Mars’ tilt, but I find them the most exciting to spot. With some diligence and a map of Mars, you can ascertain which features you are looking at. I use the SkySafari smartphone app to see what is currently visible by zooming in on Mars and tapping its features. The Red Planet rotates once every 24 hours 40 minutes, so observing it through the night will reveal different features, as will watching it over the course of a few weeks.

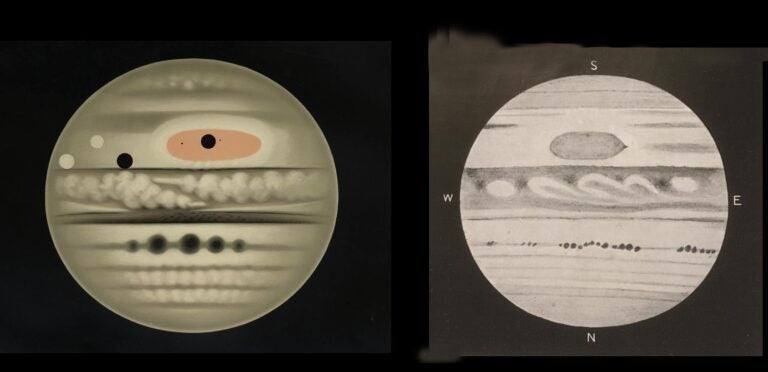

Mars also has more transient phenomena. Despite having a much thinner atmosphere than Earth, clouds do form on Mars, particularly over the large basins. The martian volcanoes also tend to attract them. Use a blue or violet filter to see the clouds more easily.

Mars is also known for its dust storms, which can sometimes encircle the whole planet — as happened in 2018. When this occurs, Mars appears light red and featureless for weeks or even months. The 2018 storm killed the Opportunity rover 5,352 sols (martian days) into its mission. These storms change the look of the martian landscape, which is why maps of the fourth planet from decades ago look different than current ones.

There are many exciting features to enjoy when gazing at Mars; one can really get the sense of how similar the dusty planet is to our own. If you can’t observe it right at opposition, don’t worry — it will remain large and bright for several weeks as its distance from Earth increases. I personally enjoy listening to Gustav Holst’s “Mars, the Bringer of War” while watching it through my telescope. Happy Mars opposition!