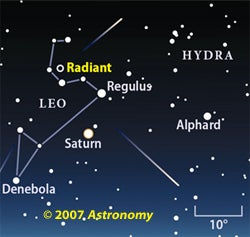

Leo the Lion hosts the Leonid meteor shower, which peaks this year in a moonless morning sky. Download a high-resolution of this finder chart for the 2007 Leonid meteor shower. Credit: Astronomy: Roen Kelly.

Astronomy news

This week’s sky events

Astronomy basics

Glossary of astronomical terms

Return to Astronomy “For the media” page

Astronomy promotes the science and hobby of astronomy through high-quality publications that engage, inform, entertain, and inspire. WAUKESHA, WI – Skygazers can catch 10 to 15 shooting stars streaking through the early morning sky each hour November 18. This marks the peak of the annual Leonid meteor shower, best known for occasionally spectacular shows. Astronomers aren’t expecting any enhanced activity this time out. Instead, observers can enjoy a typical Leonid peak with little interference from moonlight.

Video notice: Watch Astronomy Senior Editor Michael Bakich’s video about how to watch a meteor shower.

Experts at your disposal

Astronomy magazine editors are available to discuss this spectacle. To request an interview, please contact Matt Quandt at 262.798.6484 or mquandt@kalmbach.com.

When Earth runs into comet debris, the particles burn up in our atmosphere and create the fiery streaks of light astronomers call meteors. The Leonid shower is so named because the meteors appear to emanate from a point in the sky – called the radiant – that lies within the constellation Leo.

By local midnight November 17/18, the radiant is high enough for a good view. The First Quarter Moon sets at about the same time, which makes for a darker, more meteor-friendly sky. Over the next few hours, meteor rates will increase to 10 to 15 per hour as Leo climbs higher.

Leonid meteors travel faster than those of any other shower – 162,000 mph (261,000 km/h). In the hour or two before dawn, Leonids strike Earth’s atmosphere head on. This results in many bright flashes and some fireballs (meteors brighter than Venus, the brightest planet). Fireballs easily pierce twilight, so keep watch as the background stars fade with dawn’s approach.

Fishing for comet dust

“Meteor-watching is a minimalist activity,” explains Astronomy magazine Senior Editor Francis Reddy. There’s no equipment required – skygazers just need to know when and where to look. “Dress warmly, relax in a comfortable chair, and keep an eye on the eastern sky,” he says. “It’s kind of like fishing.”

The most notable feature of the Leonid shower is its habit of producing periodic, dramatic meteor “storms.” During these brief but intense displays, when observers may see a meteor every few seconds, Earth intercepts dense streams of dust ejected during past returns of Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle.

Our planet passed through such streams annually from 1998 to 2002, but as the parent comet moves away from the Sun, so does its debris. Observers noted mild upticks in meteor rates after 2003, but astronomers expect a return to normal this year. Then again, surprises are always possible with the Leonids.

While you’re out, take the time to locate Regulus, the brightest star in Leo, and the planet Saturn, which now lies less than 8° below it. Mars makes another good target. It’s the bright, ruddy, star-like point almost directly overhead at 3 a.m.

Don’t forget the Taurids

Another meteor shower is also active at the time – the Southern Taurids. Visible between October 1 and November 25, this is the strongest of several streams originating from Comet 2P/Encke.

The shower’s maximum of 15 meteors per hour occurs November 3 through 5. Taurid meteors are generally faint and quite slow, as meteors go. The particles approach Earth from behind and must catch up to us, so these meteors travel at a comparatively leisurely pace: 68,000 mph (110,000 km/h), or less than half Leonid speed.