The planets offer exciting views in April. Jupiter is a brilliant object in the evening sky, although the observing window narrows as the Sun sets later each day. Mars is past its best, but remains bright and high in the sky. Mercury, Venus, and Saturn make an early-morning appearance before sunrise. And a special treat is the annual Lyrid meteor shower, which peaks in the month’s third week.

Early April is your last chance to spot Uranus. It’s a binocular object shining at magnitude 5.8 near the border between Aries the Ram and Taurus the Bull.

Scan about 4.5° south of the Pleiades (M45) with 7×50 binoculars to find a pair of 6th-magnitude stars lying east-west. These are 13 and 14 Tauri. Now, move 3° southwest to find a dimmer pair of stars, wider in separation, also lying east-west. On April 1, Uranus stands less than 1° northwest of the westernmost star of this second pair. By the 15th, it stands 0.9° due north of the same star.

Uranus is brighter than the stars and easy to track with binoculars. Catch it early, because it sets within two and a half hours of sunset on the 15th and becomes lost in twilight by the end of April.

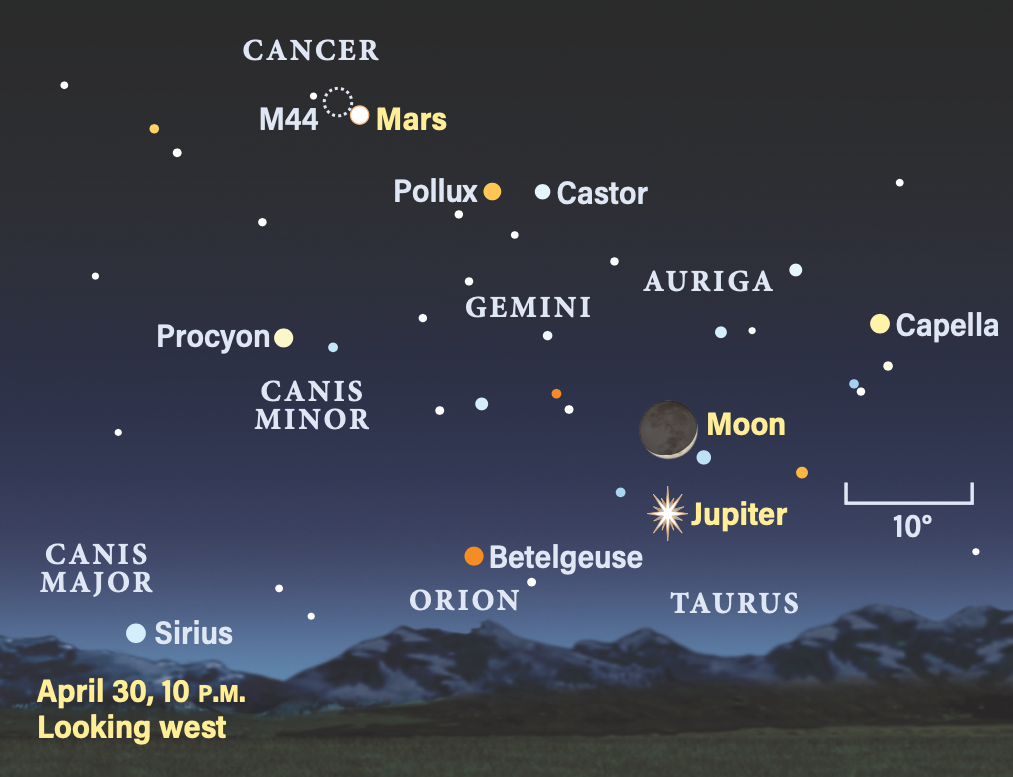

The window for observing Jupiter narrows this month as later sunsets impact dark time. On April 1, Jupiter stands 46° high an hour after sunset, and sets by 1 a.m. local daylight time. On April 30th, it’s down to 24° in altitude an hour after sunset and sets nearly an hour before midnight.

Jupiter’s brightness dips 0.1 magnitude over the month to reach magnitude –2.0. Still, it dominates the constellation Taurus, already chock-full of gorgeous sights like the Hyades, Pleiades, and the red giant star Aldebaran. On April 1, a crescent Moon, complete with earthshine in late twilight, stands 3° east of M45. This is such an evocative scene that you will want to sit and watch as they slowly set in the west.

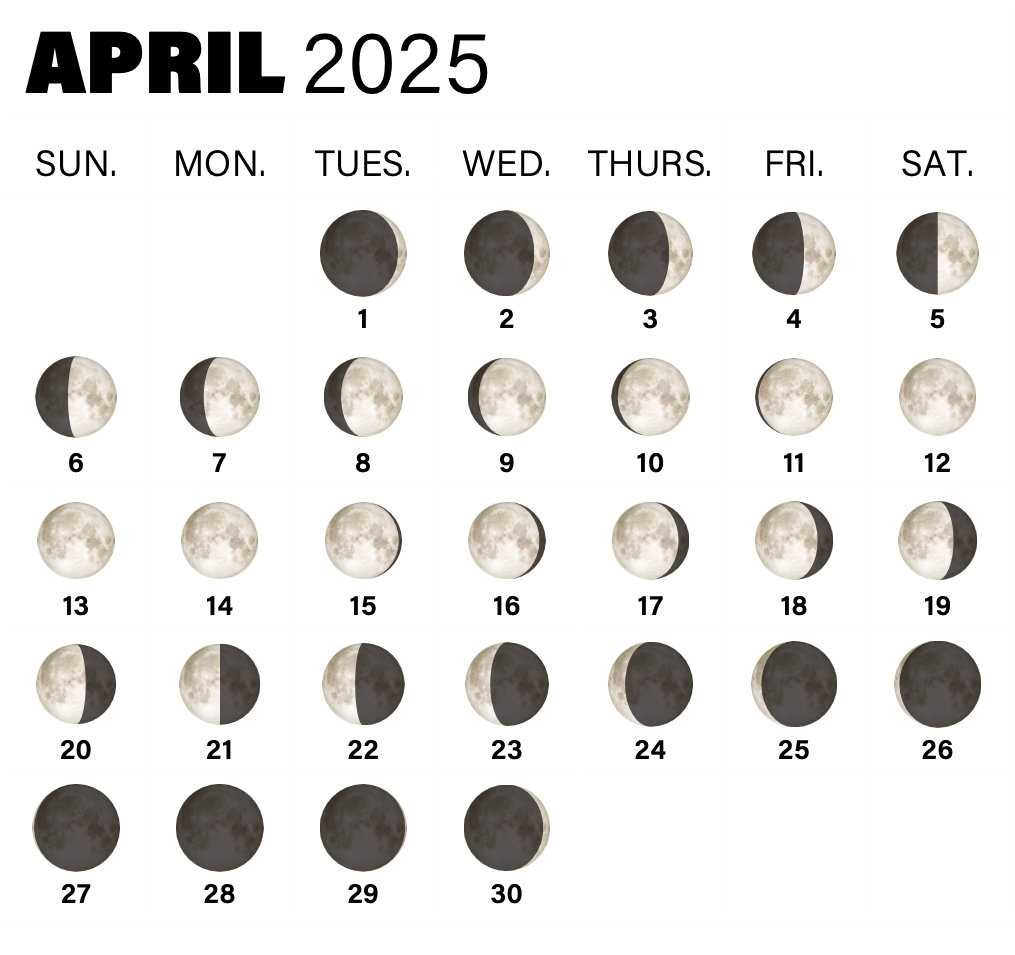

You’ll find Jupiter and the thin crescent Moon side by side April 2, and again on the 30th.

Jupiter’s apparent diameter, easily viewed through any telescope, declines from 36″ to 34″ during April. The planet’s cloud belts are evident at a glance, but don’t settle for the two dark equatorial belts. Patient viewing allows your eye to get used to seeing subtle shading on the planet and reveals a wealth of detail, particularly during moments of good seeing.

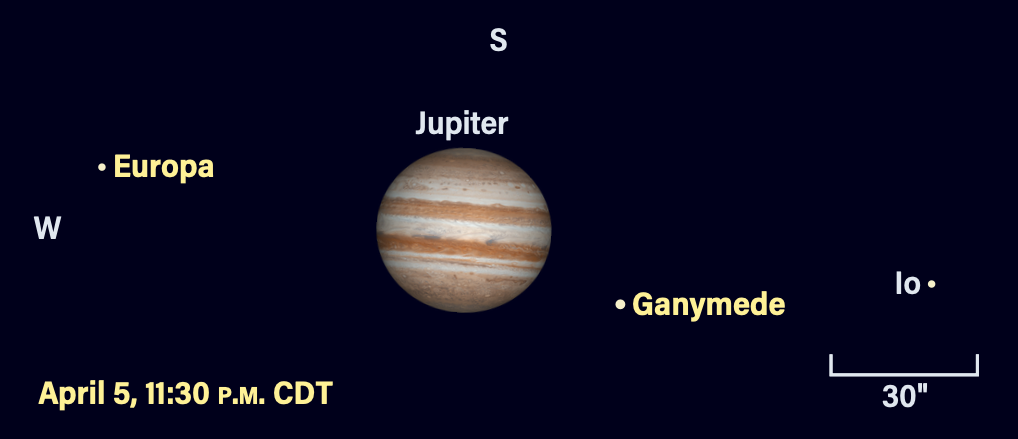

Jupiter’s Galilean moons continue performing, orbiting the planet in periods ranging from two to 17 days. The inner three, Io, Europa, and Ganymede, have resonant periods, with Europa and Ganymede continuing a series of events from last month.

On April 1, you’ll find Europa and Ganymede some 10″ apart to the east of the planet’s disk. Seven days later, on the 8th, they are back together, now 18″ apart to Jupiter’s east. The pairing occurs again on the 15th, when they stand 30″ apart; on the 22nd, they’re 40″ apart. Finally, on the 29th, the two moons are 55″ apart. Each of these near conjunctions occurs a greater distance east of the planet.

An interesting Ganymede event occurs April 5, when it reappears from behind Jupiter’s disk around 10:22 p.m. EDT (this occurs in twilight in the Mountain time zone). Just over two hours later, Ganymede enters into Jupiter’s vast shadow, which extends to the east of the planet from our earthbound perspective. Watch the moon slowly fade out, starting just before 11:30 p.m. CDT (note the time zone change) and taking several minutes to disappear. Jupiter is getting low in the Midwest, so the eclipse is best seen from the Mountain and Pacific time zones.

Io undergoes many transits, orbiting the huge planet in 1.77 days. The moon and its shadow are crossing the disk as night falls in the mid-U.S. on April 11. Io exits at 10:46 p.m. EDT, while its shadow appears as a black dot in the center of Jupiter. The shadow exits 66 minutes later.

Europa undergoes a similar sequence the next evening (April 12). As the moon exits the disk around 10:20 p.m. EDT, its shadow has only just begun to transit and doesn’t reach the middle of the disk for another 50 minutes. This is because Europa’s orbit is larger than Io’s. Also notice that Ganymede is approaching the northwestern limb of the planet, setting up an occultation. Ganymede begins to hide behind Jupiter just before 10:10 p.m. MDT. (Note the time zone change, as Jupiter is now very low in the Central time zone.) Europa’s shadow exits the disk just under 20 minutes later.

Io transits again on the 18th, followed again the next day by Europa. This time, on the second evening Ganymede is well off the western limb, not reaching occultation before the planet sets.

As April opens, Mars stands 70° high in the southern sky in Gemini an hour after sunset. It shines at magnitude 0.4 on the 1st, brighter than either of Gemini’s brightest stars, Castor and Pollux. On April 1, you’ll find the 4th-magnitude star Kappa (κ) Geminorum less than a Moon’s-width north of Mars. By the 10th, Mars stands in line with Castor and Pollux, 5.5° from the latter.

Mars crosses into Cancer on the 12th and its nightly path makes a beeline for M44, the Beehive star cluster. By April 30, Mars stands 2° northwest of the fine cluster, truly a spectacle in binoculars or low-power scope.

Through larger telescopes, Mars remains challenging as it recedes from Earth. It’s a tiny 8″ in diameter on April 1; martian surface features are hard to spot and it’s well past its best. The apparent diameter shrinks to just under 7″ by the 30th. Distinctly noticeable is the 90-percent-lit disk.

Mars sets around 3:30 a.m. local daylight time on April 1, and more than an hour earlier by the 30th.

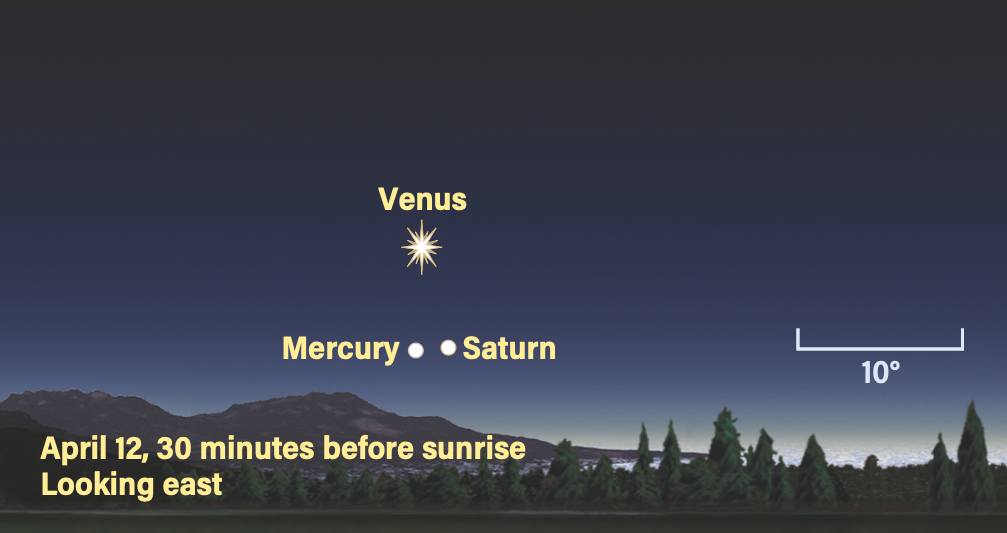

Venus, Mercury, and Saturn reappear in the morning sky. Venus is easier to spot due to its brilliance, particularly if you have a clear eastern horizon. On the 1st, it appears low in the east an hour before sunrise. At magnitude –4.2, it’s easy to spot soon after rising. By the 15th, Venus is magnitude –4.7 and stands 12° above the horizon at 6 a.m. local daylight time. On the 1st, a telescope shows a slender, 4-percent-lit crescent spanning 57″. A week later, it’s 52″ wide and 8 percent lit.

Venus’ appearance in a telescope continues to change quickly as the planet’s separation from the Sun increases. On the 15th, the disk spans 47″ and is 15 percent lit. By April 30th, the phase has expanded to 28 percent lit and the disk has shrunk further to 37″, due to its increasing distance from Earth.

Mercury begins the month shining dimly but brightens as it approaches its April 21 western elongation. One challenging opportunity occurs the morning of April 12, when Mercury and Saturn stand side by side, with 2.2° separating them. They are about 7° below Venus, which acts as a bright signpost to find the much dimmer pair. Mercury is magnitude 0.9 and Saturn shines at magnitude 1.2, both difficult in advancing twilight. The pair rises around 5:30 a.m. local daylight time and sunrise is less than an hour later, so a very clear and transparent sky with a clear eastern horizon is needed to spot the planets.

Mercury brightens to magnitude 0.4 by the 21st, when it rises nearly an hour before the Sun. During the last week of April, Mercury continues brightening, although its angular separation from the Sun is now declining. It achieves magnitude 0.1 on the 30th, and by 6 a.m. local daylight time stands 9° above the eastern horizon.

Saturn is a dim 1st-magnitude object in morning twilight. The ringed planet rises at 5 a.m. local daylight time in late April and stands nearly 5° above the horizon by 5:30 a.m. for mid-latitudes (40° north). A waning crescent Moon hangs within a few degrees of the planet on April 24 and 25. Saturn passes 4° due south of Venus on the 28th.

Telescopic views of Saturn, while tricky in the oncoming twilight, are worthwhile to glimpse the very fine shadow of the rings on the 16″-wide disk. Following the ring-plane crossing in March, we are now looking up at the southern face of the rings, but the Sun still illuminates the northern side until the first week of May. Our view of the backlit ring system offers a unique sight for a short time, worthy of an early-morning excursion.

Neptune is still close to the Sun and not visible early in the month. By the end of April, the magnitude 5.8 ice giant is 5° high in the east an hour before sunrise, very challenging to view.

European observers experience a lunar occultation of the Pleiades on April 1/2. The 3.5-day-old crescent Moon crosses the many stars in the cluster over a roughly two-hour period. A small telescope (60 to 90 mm) or even binoculars will show many of the brighter stars undergoing occultation, disappearing behind the dark limb of the Moon. Many 7th- and 8th-magnitude stars are occulted as well, observable in larger telescopes.

Rising Moon: On the edge

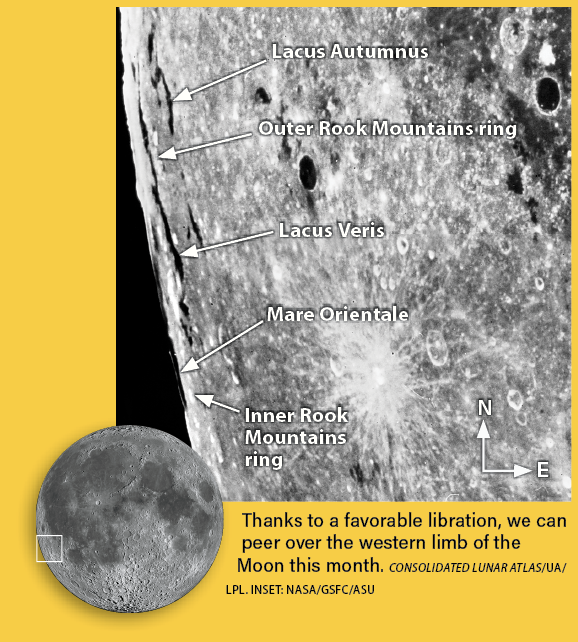

The most striking impact basin on the Moon is arguably Mare Orientale, a sea of frozen lava surrounded by a huge, well-defined double ring of rugged mountains that spans almost 600 miles. You’re forgiven if you haven’t heard of it, because it is tucked far against Luna’s western limb, its eastern ramparts and lava lakes visible only when the lunar spin and elliptical orbit line up. This favorable libration (apparent tilt) occurs between the 18th and 24th, and similarly for the next month toward Third Quarter, but not again for another year.

Orientale is all about observing at the edge — literally. We’re peering over the raised rim of the Cordillera mountains to view a narrow, snaking form of lava named Lacus Autumni. Use the recognizable Grimaldi to orient yourself. Another dark, long line is Lacus Veris. We’re now looking beyond the tall ring of the outer Rook mountains into the shallows where lava welled up from below, then onward until we reach the light colors of the lunar crust pushed up into the inner Rooks.

Tucked right against the limb is the darker central floor of Mare Orientale. When Orientale formed, the denser mantle underneath bulged upward, creating a mass concentration. This so-called mascon affects spacecraft orbits, causing a slow shift in response to the extra gravitational force. Sunlight angles can make all the difference when observing. The picture here shows the back inner wall of Orientale (longitude 100 west) as the thinnest of white lines on the very limb, illuminated by a late-morning Sun in the lunar sky. If it was late afternoon, that wall would be in shadow, no longer helpful in tracing the outline of this youngest of giant impact features.

Last Quarter is best just before sunrise, making it ideal for a grab-and-go scope view before heading off to work or listening to the dawn chorus of birdsong over coffee.

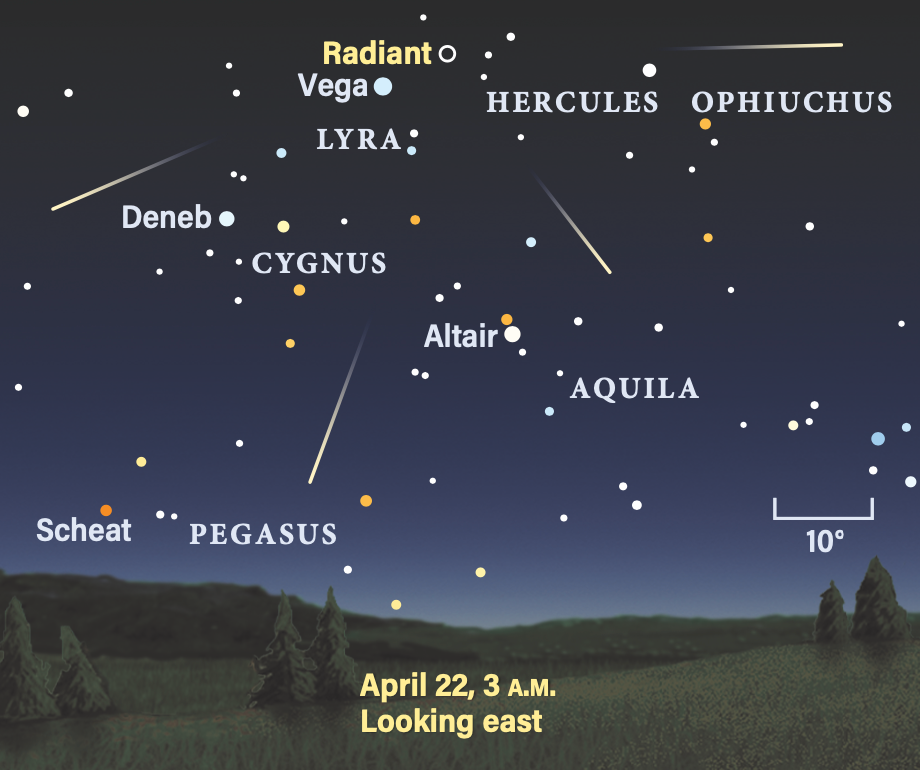

Meteor Watch: Ancient debris

Skies will be dark for the annual Lyrid meteors, which are active from April 14 to 30. On the day of the peak, April 22, there’s a waning crescent Moon that doesn’t rise until nearly 4 a.m. The radiant of the shower, near Vega in Lyra the Lyre, is already 30° high by midnight, offering many hours to catch the fleeting meteors as they skip into Earth’s atmosphere and burn up.

An older meteor shower, the Lyrids are associated with the 416-year orbit of Comet C/1861 G1 (Thatcher). Its debris has spread out with time, reducing the hourly rate to modest amounts. The Lyrids are expected to produce about 20 meteors per hour once the radiant is nearly overhead, which occurs in the hour before dawn. Expect lower rates in the earlier-morning hours.

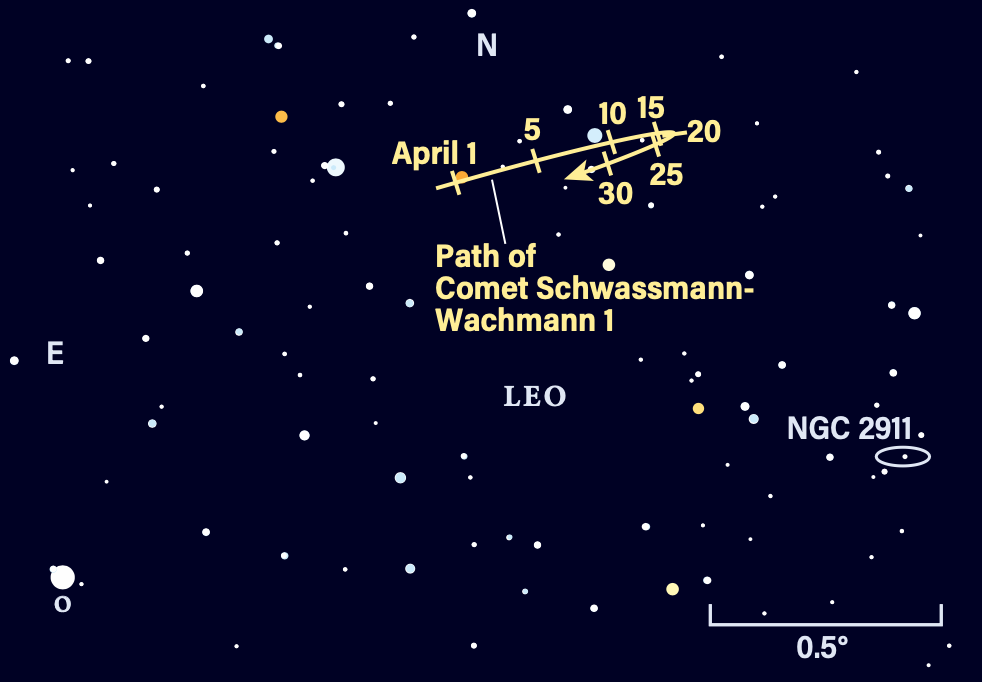

Comet Search: Pushing the power and yourself

Barring another fast-moving surprise visitor from the Oort Cloud, this year’s comet roster is a suite of challenging ones, with one hopeful that goes into outburst regularly. Now’s the opportunity to upgrade your high-power deep-sky skillset.

Our target is enigmatic 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann. Orbiting between Jupiter and Saturn, it’s classified as a Centaur. More than once a year, it undergoes mini-explosions to jump to 11th magnitude as expelled dust scatters sunlight back to us, bringing it within range of an 8-inch scope under a dark sky.

First calibrate yourself with galaxy NGC 2911, 1.8° west of Omicron (ο) Leonis, itself a bit west of Regulus. At magnitude 11.5 and covering 2′, the galaxy makes a great doppelgänger for a fainter comet, including soft edges and increasing brightness into the core. When you go for magnifications above 150x, the field gets unsettlingly dark at first, but stick with it and focus on the 8th- to 9th-magnitude stars nearby. Tap the scope gently to trigger your eyes’ peripheral motion reception. Relax, sit down if possible, and use a dark towel over your head to block out stray light.

Shift north 1° to a magnitude 7.7 star and use those skills to suss out Schwassmann-Wachmann. You can even try 200x for small objects like these.

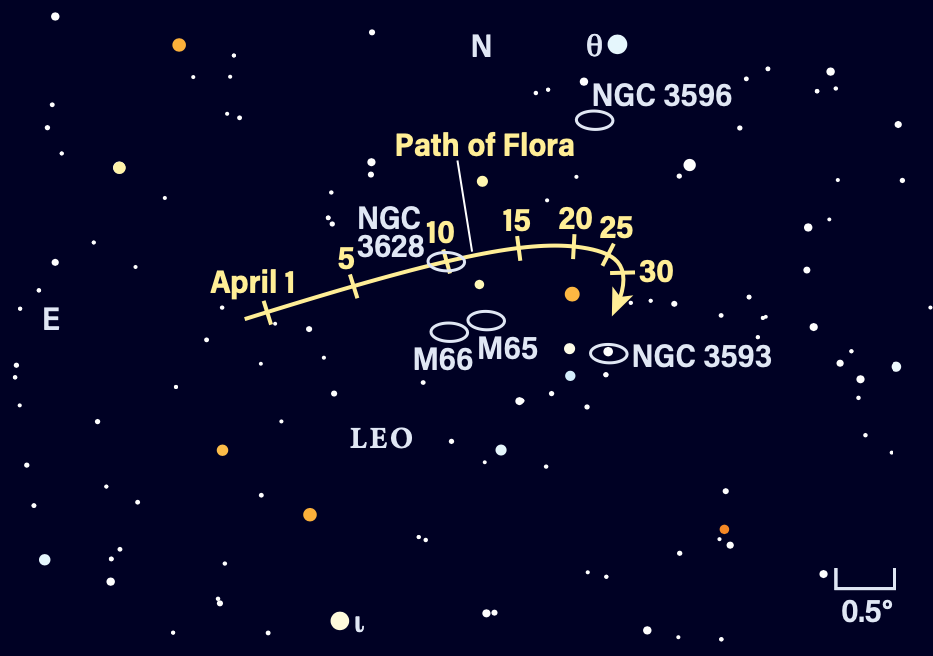

Locating Asteroids: Photobombing the Leo Triplet

Here’s some fun for both visual observers and imagers: Main-belt object 8 Flora is passing in front of a most popular deep-sky field.

From the suburbs, a 6-inch scope will readily show the 10th-magnitude dot in the sparse star field. By making a sketch with three or four dots and returning on another night, you can see it shift position. Although galaxies struggle in light pollution, M65 and M66 have decently bright cores that can rise to visibility for patient observers. The key here is to forget the images that show expansive halos and simply look for a very small, fuzzy “star.” Try powers above 120x and take your time.

Imagers love revealing the long dust lane of the edge-on galaxy NGC 3628 just to the north of M65 and M66. Flora will be very close to tracking down this dark channel over the course of four nights, from the 8th to the 11th. A two-hour session generates a 20″-long streak. The nearby Moon will lighten the background considerably.

Flora was picked up visually by John Hind in 1847 as an interloper not shown on his star charts. In our lifetime, it has been measured to be just out of round and 90 miles across.

Star Dome

The map below portrays the sky as seen near 35° north latitude. Located inside the border are the cardinal directions and their intermediate points. To find stars, hold the map overhead and orient it so one of the labels matches the direction you’re facing. The stars above the map’s horizon now match what’s in the sky.

The all-sky map shows how the sky looks at:

midnight April 1

11 P.M. April 15

10 P.M. April 30

Planets are shown at midmonth