Venus is a bright evening star for a short period after sunset, beckoning skywatchers to view the oncoming string of planets. Saturn puts on a great show when it rises in the late evening. You can also grab a pair of binoculars to spy Uranus and Neptune — we provide guides below. The real spectacle of the month is the conjunction of Jupiter and Mars in Taurus on the 14th, visible in the early-morning hours. It’s one sight you won’t want to miss.

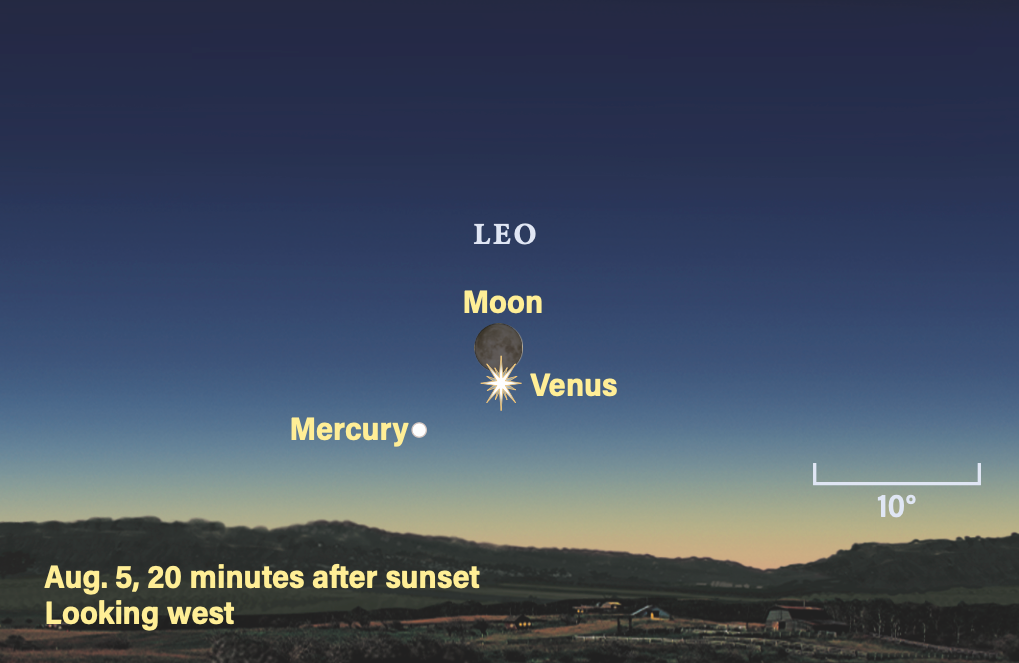

Venus is striking once the Sun sets in the west. Standing 3° high 30 minutes after sunset, it shines at magnitude –3.9. It’s an easy object if you have a clear horizon, though its visibility only slightly improves throughout the month. On the 4th, Venus stands 1° north of Regulus, a 1st-magnitude star in Leo that will require binoculars or a small telescope to spot in the bright evening twilight. On Aug. 5, a crescent Moon joins the scene, with Venus 1° west of our satellite — again a challenging view, since the two set an hour after sunset.

By Aug. 31, while the elongation of Venus has grown to 24° east of the Sun, the angle of the ecliptic to the western horizon hasn’t improved, so Venus remains only 5° high 30 minutes after sunset. Venus is on the far side of the solar system with respect to Earth and presents an almost full disk (92 percent lit) in a telescope, spanning 11″.

You might spot Mercury on Aug. 1 standing 8.7° to the left of Venus in the sky for mid-northern latitudes. It shines at magnitude 0.9 and may be easily mistaken for Regulus (magnitude 1.4), which lies about midway along and above a line joining the two planets.

Mercury quickly sinks out of view and reaches inferior conjunction with the Sun Aug. 18. After that it reappears in the morning sky, reaching magnitude 1 on the 30th. Look for it on the 31st, when it hangs 13° below the waning crescent Moon as the planet rises some 80 minutes before the Sun.

Saturn is next to rise in the evening, appearing over the eastern horizon at about 10 p.m. local daylight time on Aug. 1. It is up two hours earlier by the end of August. The ringed planet is a month from opposition and is a fine object. Starting the month at magnitude 0.7, it’s easy to spot among the much fainter stars of Aquarius. The planet stands 1.5° south of 4th-magnitude Phi (ϕ) Aquarii, a star familiar to recent followers of Neptune.

As its distance from Earth slowly diminishes, the angular size of Saturn’s disk in a telescope grows imperceptibly from 18.7″ to 19.2″. The polar diameter is 17″, showing more than 10 percent flattening of the disk, obvious now that the ring system is close to edge-on.

The rings widen slightly as their tilt grows from 2.5° to 3.5°, as our orbital path carries us slightly above the plane of the rings. This will continue through November, when they reach a peak of 5.2° and then head toward the next ring-plane crossing in March 2025.

The satellites of Saturn cross in front of or behind the planet, although only Titan is easily visible through small telescopes. Others may be captured with high-speed video and image refinement.

Titan shines at magnitude 8.4 and orbits every 16 days. On July 31/Aug. 1, Titan transits the southern pole of Saturn starting around 1:15 a.m. EDT (11:15 p.m. MDT on July 31), although Saturn is at an elevation of only 20°. This transit lasts just over two hours, with latter parts visible from the western U.S. Eagle-eyed observers with large scopes under optimal seeing conditions may spot Dione transiting Saturn starting an hour later.

Titan undergoes a brief occultation behind the northern limb of Saturn between about 12:05 a.m. and 2:05 a.m. EDT Aug. 8/9 (note the event starts late on the 8th for time zones west of Eastern). These are the last events involving Titan for a while, since later in August the moon misses Saturn as the angle of the plane of its orbit increases from our perspective.

Fainter moons (such as 10th-magnitude Tethys, Dione, and Rhea) skim the edge of the rings as seen from Earth and sometimes transit or enter an occultation, although they are very difficult to observe. Iapetus reaches superior conjunction Aug. 15 and stands about 1′ due south of Saturn. It shines near 11th magnitude and in the second half of August moves east of the planet, fading as its darker hemisphere turns earthward.

Neptune stands 12° east of Phi Aqr, across the border in Pisces the Fish. It rises 20 minutes after Saturn. At magnitude 7.7 it is reachable with binoculars; mounting them on a tripod will improve the ease of detection. Southeast of Pisces’ Circlet asterism is a parallelogram of four stars shining at 4th and 5th magnitude. Neptune stands just north of this group, 1.6° north of the northwestern star in the parallelogram asterism on the 1st.

A telescope reveals the small, 2″-wide disk if your seeing conditions are calm. The planet is one month from opposition and will soon be visible all night.

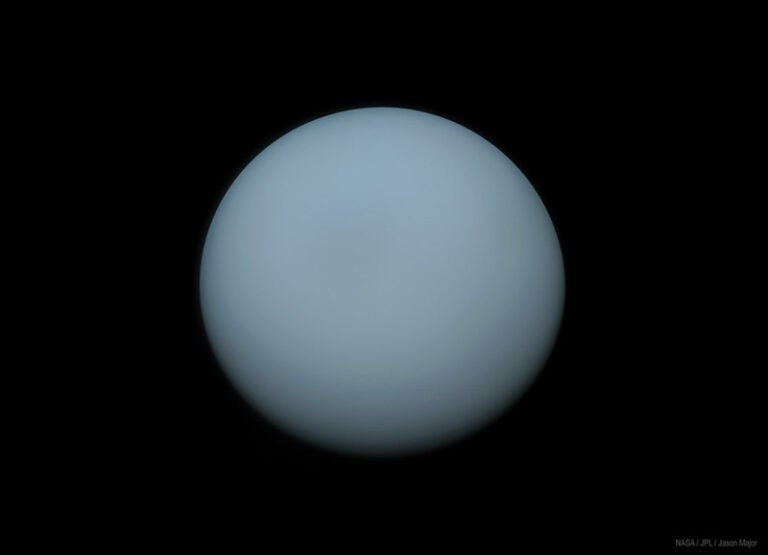

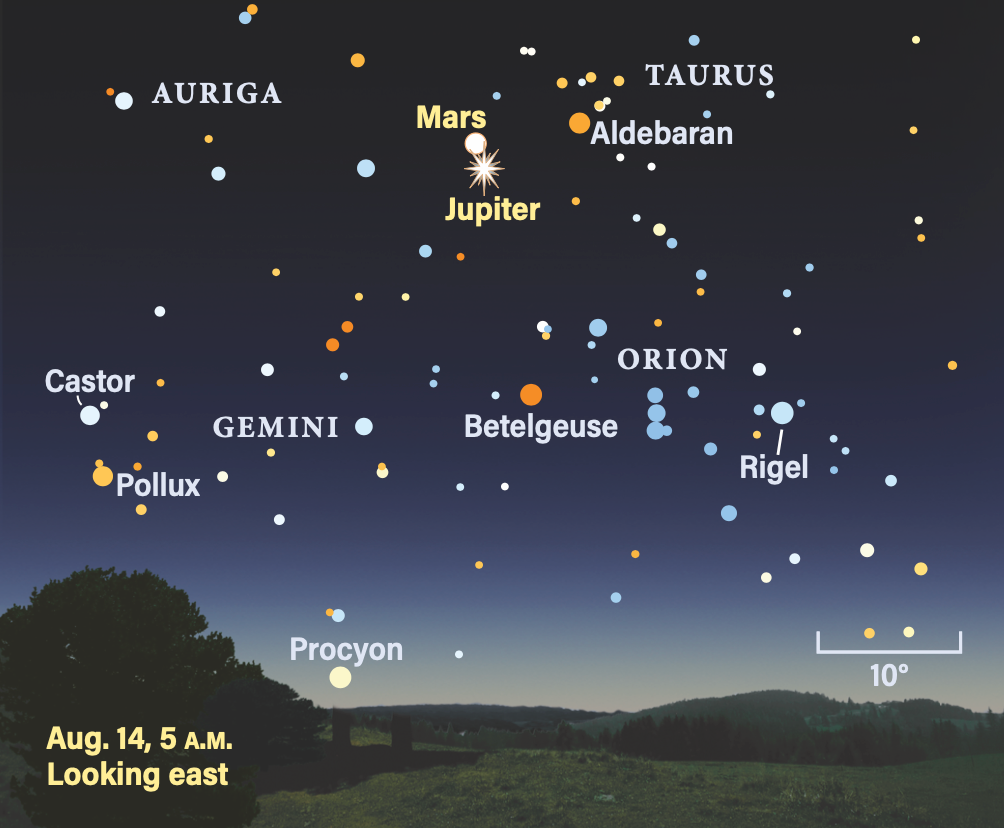

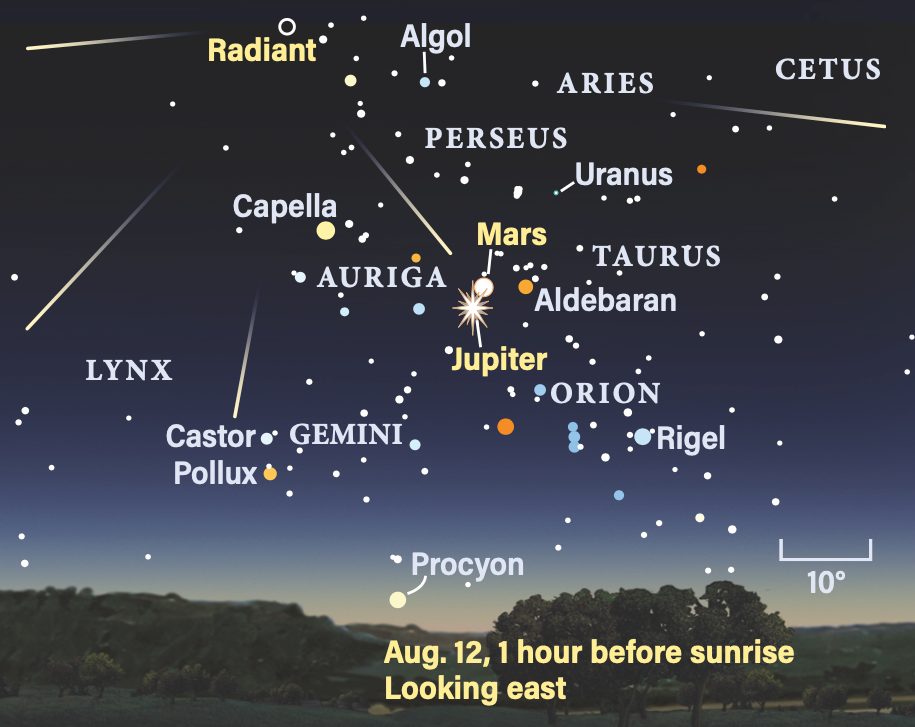

It’s well worth observing in the morning, as Taurus the Bull houses three major planets. Uranus is first to rise, shortly before 1 a.m. local daylight time on Aug. 1. It stands just over 5° south-southwest of M45, the Pleiades star cluster. Shining at magnitude 5.8, the planet can be spotted in a pair of binoculars. You’ll notice it wandering east each night. There’s a pair of 6th-magnitude stars, 13 and 14 Tauri, similar in brightness to Uranus and 1.5° northeast of the planet’s location. This gap closes to 1° during the month.

Through a telescope, Uranus shows a 4″-wide disk. This distant world is four times wider than Earth and is home to many storms whisking through its atmosphere, though they can’t be seen with amateur scopes.

Mars is now a stunning object north of Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus. The Red Planet starts August at magnitude 0.8, just 0.1 magnitude brighter than Aldebaran. Suddenly the Bull has not just one eye but a pair of them. On the 5th, Mars is 5° north of the star. And the gap between Mars and Jupiter is now under 5°.

Watch the two planets over the following nine days, as the easterly motion of Mars carries it closer to Jupiter. On Aug. 14, they stand less than 20′ apart. Jupiter shines at magnitude –2.2 and Mars is about 16 times fainter. Aldebaran stands 8° southwest of the pair.

Through a telescope Mars remains tiny, as its distance from Earth is nearly 140 million miles. It spans 6″. Jupiter, nearly four times farther, spans 37″, a reflection of its gargantuan size. Features on Mars are difficult to discern. At the end of the month, the main dark feature, Syrtis Major, comes into view for observers across the U.S.

Mars continues east across Taurus, standing 1.1° north of the Crab Nebula (M1) on the 26th and ending the month 3° northeast of Zeta (ζ) Tauri.

Jupiter dominates the morning sky, rising just before 2 a.m. local daylight time on Aug. 1 and at local midnight on the 31st. An hour before dawn on Aug. 31, Jupiter is nearly 60° high, a great target for visual observing and high-speed video capture.

A waning Moon just one day past Last Quarter stands 5.3° north of Jupiter on the 27th. Jupiter, like Mars, wanders east across central Taurus but at a slower pace than the Red Planet, owing to the gas giant’s greater distance from Earth.

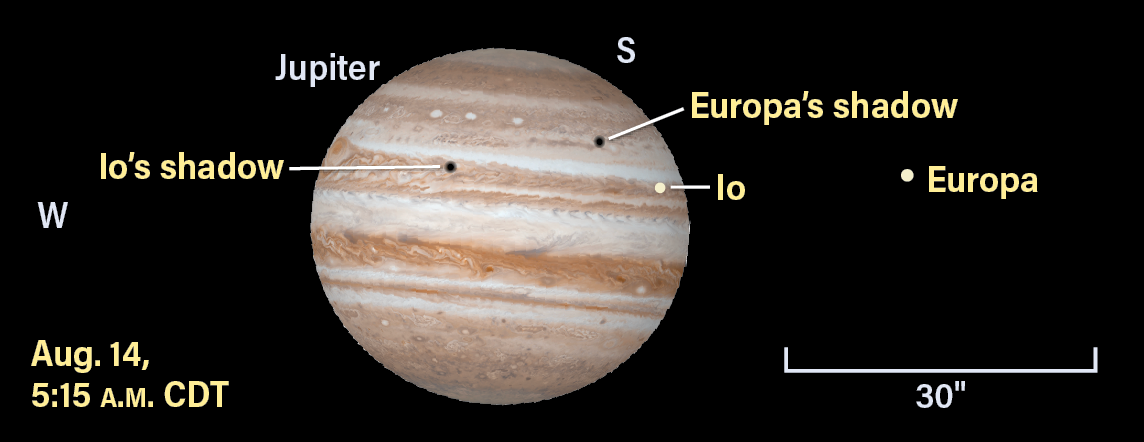

The Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto undergo a variety of events visible in small telescopes. On Aug. 14, there are two shadow transits — of Io and Europa — plus Io itself in transit, making it a triple event. With Io and Europa well to the east of Jupiter, their shadows fall on the cloud tops beginning with Io’s at 4:41 a.m. EDT. It takes 2 hours 9 minutes to cross Jupiter. Europa’s shadow is next, shortly after 5:30 a.m. EDT, followed soon after by Io, which starts its transit around 5:55 a.m. EDT. For nearly an hour the three features — two shadows and one moon — cross the disk. Notice how Io catches up to Europa’s shadow because Io is orbiting faster and in a smaller orbit than Europa.

Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, undergoes a few events this month. On the 9th, the large moon begins a transit across the south polar region at 3:38 a.m. EDT. (Jupiter hasn’t risen for western states yet.) With the transit underway, it’s also fascinating to watch Callisto below Jupiter a short distance away, missing the planet due to the inclination of the plane of the jovian moons’ orbits as seen from Earth. Ganymede’s transit ends at 5:36 a.m. EDT, this time largely visible across the country.

On Aug. 23, Ganymede’s shadow transits in twilight for those in the Mountain and Pacific time zones. Its huge shadow appears on the southeastern limb beginning around 4:46 a.m. MDT; it takes several minutes until the full dark shadow is visible. The transit lasts nearly two hours.

Ganymede itself reappears from behind Jupiter on the 27th beginning around 3:46 a.m. EDT, and again takes many minutes to appear at the northeastern limb. How soon do you notice it come back into view?

Enjoy your summertime viewing of the planets!

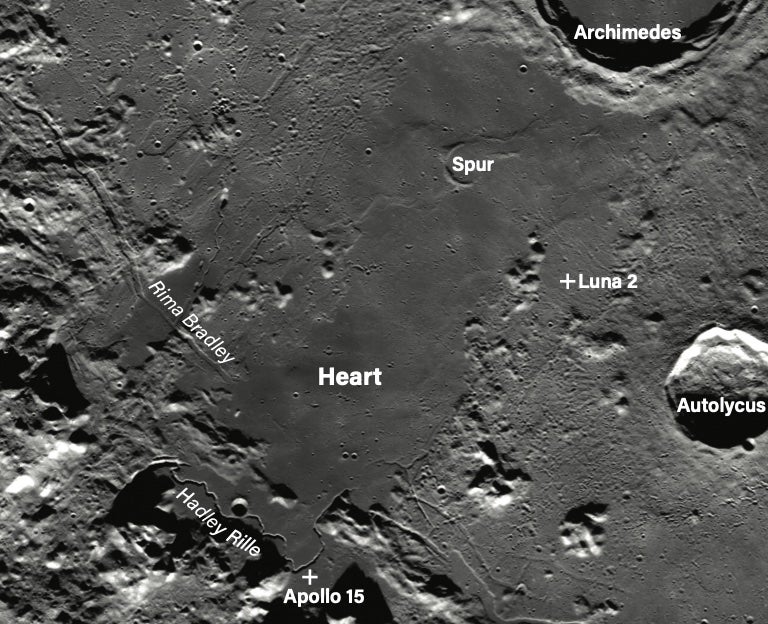

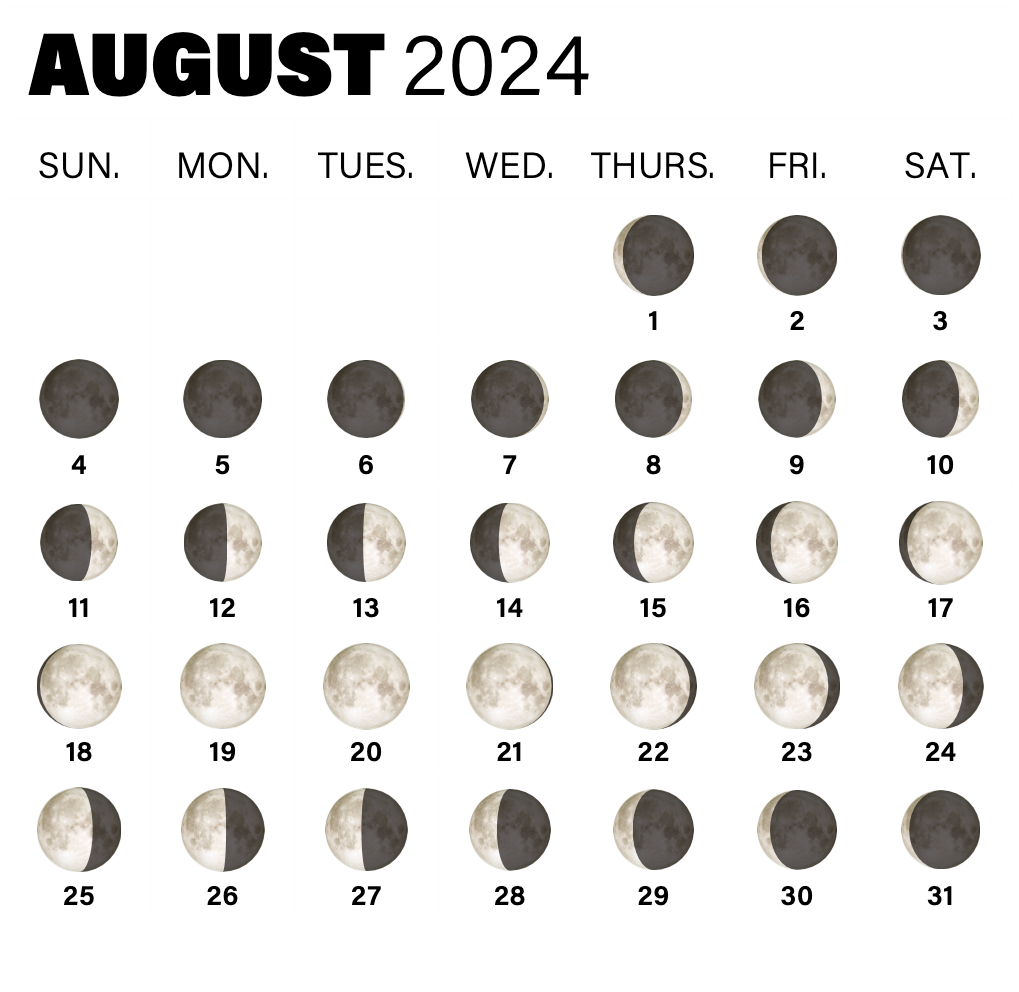

Rising Moon: An enduring favorite

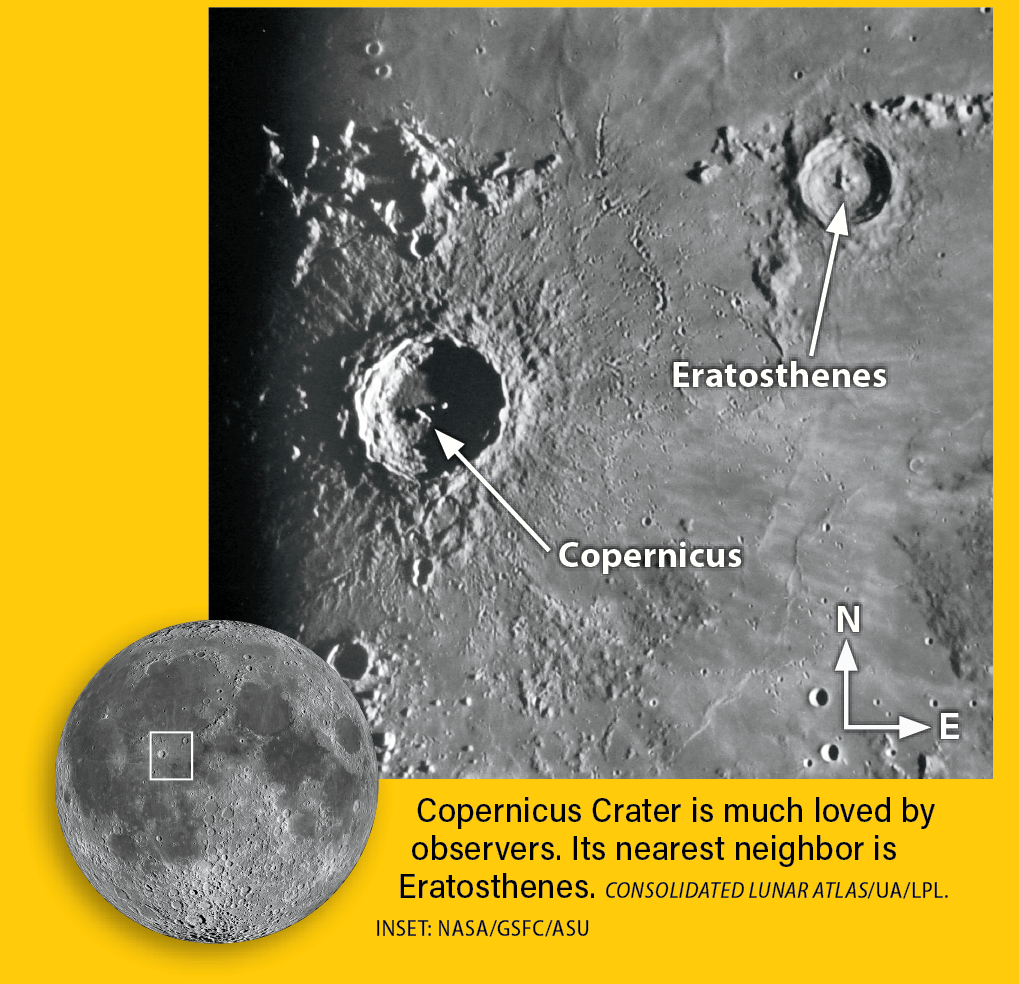

Terraced walls, complex central peaks, a rough ejecta blanket, and a ray system at Full Moon — it’s no surprise that Copernicus is visited again and again by lunar observers! The Sun rises first over the tall, modestly sharp rim on the 13th, a night after First Quarter.

Under a low Sun, the lunar topography casts long shadows, accentuating the visibility of peaks and bumps as well as holes and mild depressions. Note the jagged black teeth and spike projected onto the sandpaper-like floor. The entire crater is surrounded by an apron of fantastic texture, the result of the contents splattering outwards in all directions shortly after impact. Lunar geologists call that an ejecta blanket.

The terraces are a delight at high power. Dig a hole in a wet sandy beach and within seconds, the steep walls collapse inward to form giant staircases down to the floor. Sharp-eyed observers have noted that the terraces here are tilted down on the outside based on how the higher inner edge casts a shadow rimward. On the night of the 14th, the eastern terraces become visible. In case you get clouded out, the sequence almost repeats on Sept. 11, but with an even lower Sun angle than the image shown here.

For a few days on either side of Full, the nearly overhead Sun beats down on the 60-mile-wide impact crater. Thread in a filter to reduce the glare, pump up the power, and take in the scenery. The rough terrain and differences in elevation and texture have completely disappeared, replaced by a land of light rays and darker mottled mare showing through from underneath. These brightness (albedo) variations help astronomers piece together the history of the lunar surface. The impacting asteroid may have landed in a dark lava field, but the blast excavated down to the lighter-hued rocks below and hurled them outward in a fantastic system of rays.

After a good look at Copernicus under different phases, you too will keep coming back for more.

Meteor Watch: The Perseids return

The Perseid meteor shower is favorable this year. The First Quarter Moon sets around midnight, offering hours of viewing in a dark sky when we are on the leading hemisphere of Earth as we orbit the Sun. As we plow into the stream, we’ll see higher-velocity — and therefore brighter — meteors.

The shower, a result of Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, is active from July 17 to Aug. 24 and peaks Aug. 12. Both the mornings of Aug. 11 and 12 should provide good rates; if poor weather is around, try Aug. 10 and 13 as well.

The zenithal hourly rate (ZHR; when the radiant is at 90° altitude) may reach 100 meteors per hour. The radiant in Perseus rises above 60° in the hour before dawn. This attenuates the listed ZHR rate by about 15 percent, which converts to an average of more than one meteor per minute in the pre-dawn hours if you have a clear dark sky away from streetlights. From a city this value will drop by more than 50 percent, since you will only see the brightest members.

Center your view 40° to 60° from the radiant by sitting in a comfortable chair or lounger. Perseid meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but the longer streaks lie some distance from the radiant. Many bright Perseids leave a fluorescent trail called a persistent train.

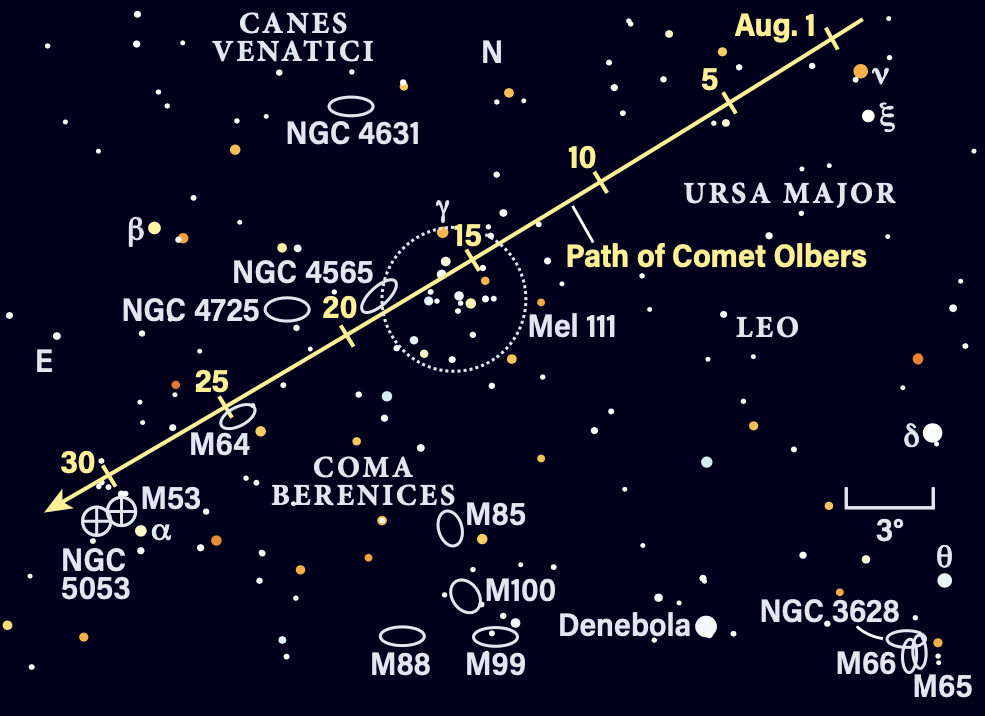

Comet Search: Tangled in stars

Prepare for October’s bright comet by studying departing 13P/Olbers. Glowing at 8th to 9th magnitude and below 25° in altitude in the evening twilight, Olbers will be tough for binoculars. Without computer pointing, arm yourself with a finder chart to get you from Alkaid at the end of the Big Dipper’s handle, down 13° to galaxy M94 (a good reference at magnitude 8.1), then down another 16° to land southeast of Nu (ν) and Xi (ξ) Ursae Majoris.

Look for a well-defined southern flank where the solar wind pushes the dust northward into a stubby tail that diffuses away. The comet likely sports a concentrated false nucleus, outshining the inner coma. Compare that form to the symmetrical one of the galaxy.

Moonlight interferes after the 10th, but imagers will want to capture the comet’s green glow lying in the sparkling strands of Berenice’s Hair with the cluster Melotte 111 for a few days starting on the 15th.

Celebrate the reopening of the moonless window on the 24th when Olbers — fading past 9th magnitude — shares a low-power field with the famous Blackeye Galaxy (M64). Push the power past 120x, be patient, and take the time to compare and contrast the two. Repeat on the 25th to hone your skills.

Locating Asteroids: Time for tea

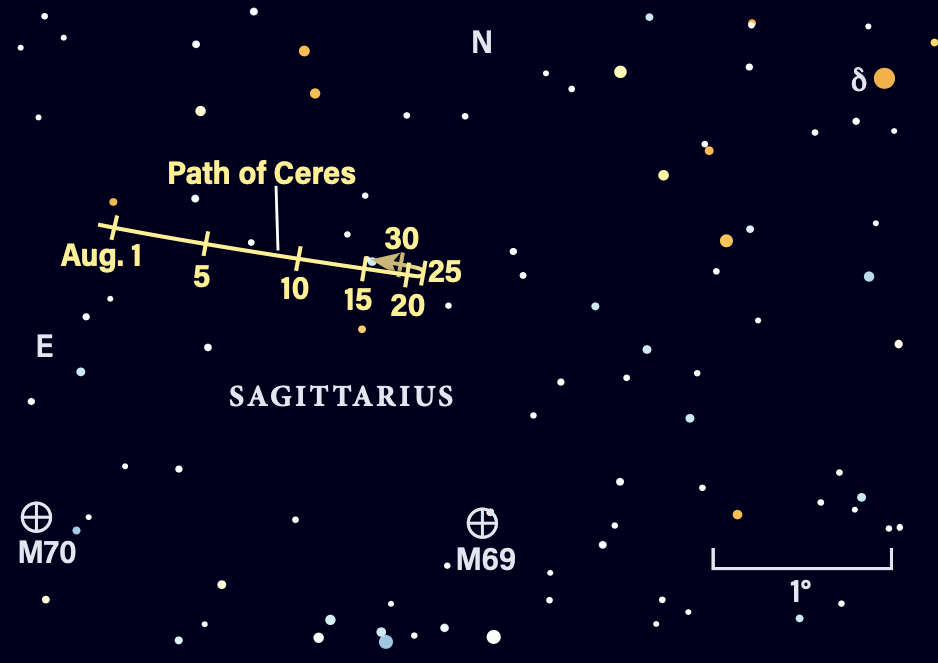

Floating in the middle of Sagittarius’ Teapot asterism, 1 Ceres steeps in the space front of the Milky Way’s central bulge. Fading slowly through 8th magnitude following last month’s opposition, the dwarf planet may be ruler of the main belt, but it could take image-stabilized 10x binoculars to spot it from the suburbs. The Moon will join the view from Aug. 14 to 16.

Print yourself a 4°-wide finder chart with stars to 9th magnitude, anchored at the west end by Delta (δ) Sagittarii, the bright star at the crook of the Teapot’s spout. Hop your way over to Ceres’ location and add a dot. During the last half of the month, the 600-mile-wide asteroid slows down, stops, then returns eastward, a result of relative movement between it and Earth.

Since Ceres stays within the same 30′ field during the latter half of the month, note which field stars are brighter, similar, and slightly fainter than the dwarf planet on the 11th or 12th, then repeat at month’s end. If you find the half-magnitude drop easy to spot, check out some of the American Association of Variable Star Observer’s (AAVSO) beginner variable stars for astrophysics in action.