December’s early-evening sky offers a slew of planetary views, beginning with Venus, Saturn, and Jupiter — all on show soon after sunset. Capture the top features of the solar system in one evening by spotting the changing phase of Venus; the spectacular rings of Saturn; and the remarkably dynamic jovian atmosphere, its Great Red Spot, and Jupiter’s four bright moons.

The first planet to appear after sunset is Venus, hanging low in the southwest. It reaches greatest brilliancy Dec. 4, when it shines at magnitude –4.9, easily piercing the bright twilight. This unmistakable brilliant jewel lies in eastern Sagittarius, featuring in all evening photographic compositions of the broad Milky Way.

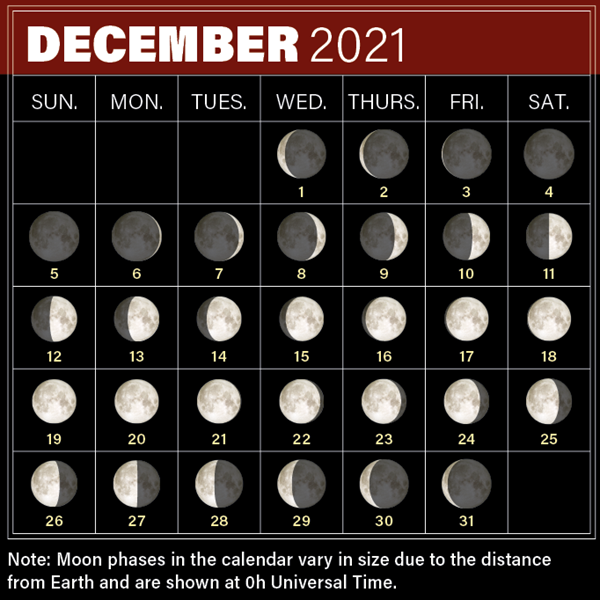

A waxing crescent Moon, complete with earthshine, joins Venus Dec. 6, standing less than 3° away. As Venus slowly approaches the Capricornus border in mid-December, an interloper, Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard), might be visible nearby if it reaches binocular brightness or better (magnitude 5). Observations of the comet Dec. 15 and 16 — after it appears in the evening sky — will give a good indication whether or not it will be easily visible.

On Dec. 17, Leonard stands 5° below Venus. Scan the region with binoculars for the fuzzy glow of the comet’s coma. If the comet is brighter than predictions, it may just reach visibility to the unaided eye and even sport a short tail. The comet remains low in altitude for the next week, and like all comets, it will be best recorded in photographs.

The next day, Venus halts its easterly trek against the starry background just short of the Capricornus border and sinks back into twilight. Track Venus with a telescope to view its changing form. On Dec. 1, it shows a 28-percent-lit crescent spanning 39″. The disk grows to 61″ by Dec. 31, but shrinks to a mere 2 percent lit. This fast transformation occurs when Venus approaches inferior conjunction, which occurs early in 2022.

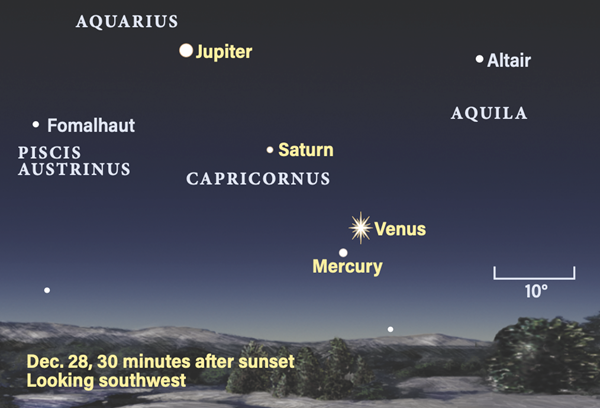

As Venus gets lower late in December, Mercury appears out of the Sun’s glare. Try spotting the innermost planet Dec. 26, when it stands less than 6° below Venus. They appear closest on Dec. 28 — 4° apart — with Mercury shining at magnitude –0.8. By New Year’s Eve, Mercury stands 1° higher than Venus. Check them out 45 minutes after local sunset.

Saturn joins Venus in the evening sky, shining a much fainter magnitude 0.6. They’re 18° apart on Dec. 1, and are closest (14° apart) on Dec. 16. Saturn remains in Capricornus all month.

Grab your last telescopic view of Saturn and its rings for the year. The ringed planet is best during the first half of the month, when it remains above about 20° altitude for up to an hour after twilight ends. In late December, Saturn is too low for good views in a dark sky. Saturn’s disk spans 16″; the long axis of its rings span 35″ and tilts 19° to our line of sight.

The easiest of Saturn’s moons to spot is Titan, shining at magnitude 8. The fainter moons become more difficult to find in poor seeing conditions when the planet is at low altitude. Saturn sets shortly after 7 P.M. local time on Dec. 31, so be sure to catch it early.

Jupiter starts December in the eastern part of Capricornus, about 16.5° east of Saturn. It shines at magnitude –2.3, but quickly dims 0.1 magnitude and then crosses into Aquarius Dec. 14. The waxing Moon stands below Jupiter on Dec. 8, while Jupiter stands 10° west of the Moon on Dec. 9.

Jupiter’s 37″-diameter disk looks great through a telescope — your best views will be as twilight descends and for the first hour or so after dark. By the end of December, Jupiter dips below 20° around 7 P.M. local time and sets by 9 P.M.

Check the configuration of its four Galilean moons — their relative positions change nightly. On Dec. 1, an occultation and eclipse reappearance occur close together. First, Callisto reappears from behind Jupiter at 9:13 P.M. EST, followed by Europa exiting Jupiter’s shadow at 11:15 P.M. EST.

Watch Io disappear behind Jupiter Dec. 4 at 9:35 P.M. EST. The following night, both Io and its shadow travel across the face of Jupiter shortly after darkness falls. Io’s transit ends at 9:14 P.M. EST, followed by its shadow 75 minutes later. Two days later, Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon, transits on Dec. 7 beginning at 9:03 P.M. EST. The event continues for more than 3 hours.

Neptune is a binocular object shining at magnitude 7.8 most of the month and located in Aquarius the Water-bearer. It stands high in the southern sky Dec. 1 and remains visible all evening until it drops very low after 11 P.M. local time. The distant planet lies 3° northeast of the 4th-magnitude star Phi (ϕ) Aquarii on Dec. 1. That night, Neptune is at its stationary point; it barely moves all month. Neptune stands 4.5° north of a First Quarter Moon on Dec. 10.

At the ice giant’s huge distance of nearly 30 astronomical units (where 1 astronomical unit or AU is the average Earth-Sun distance) from us, its disk spans only 2″ through a telescope. Use high magnification on a steady night of seeing to reveal its bluish-green disk.

Uranus stands high in the sky against the backdrop of Aries the Ram every evening and sets in the early morning hours. It lies about 11° southeast of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries. Uranus shines at magnitude 5.7, an easy object for binoculars once you find the right field of view. The ice giant stands about 3° northeast of the gibbous Moon on Dec. 14.

December is a great time to view Uranus with a telescope, given its high altitude after dark. Uranus spans 4″ with a distinctive greenish-blue hue. At a distance of 1.7 billion miles (19 AU), it’s a wonder to behold.

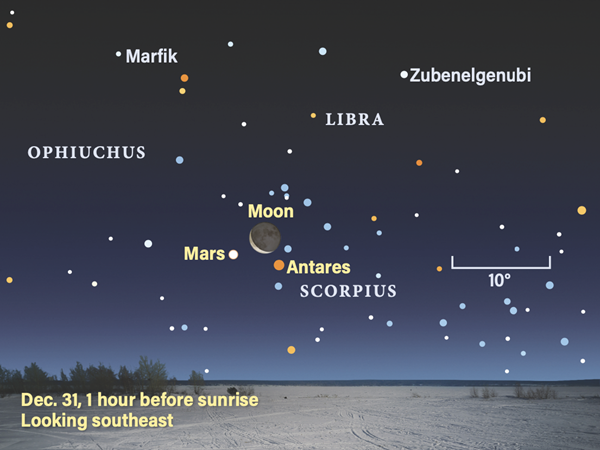

Mars reappears in the morning sky in Libra and crosses into Scorpius midmonth, then moves into Ophiuchus Dec. 25. That morning, it shines at magnitude 1.6 less than 5° north of its noted rival, Antares, which is the brighter of the two (magnitude 1.1). Mars rises nearly two hours before the Sun, so look for it low in the southeast as twilight begins. On the last morning of the year, a waning crescent Moon stands within 4° of Mars and Antares — a beautiful sight in the predawn sky.

The winter solstice occurs Dec. 21 at 11 A.M. EST.

A total solar eclipse takes place Dec. 4 across Earth’s southern pole. The longest duration of totality is 1 minute 54 seconds. A number of cruises are slated to travel to locations along the eclipse track. The eclipse begins at sunrise in the South Atlantic Ocean and crosses Coronation Island, the largest of the South Orkney Islands. The eclipse path then crosses the Weddell Sea and makes landfall again on the Ronne Ice Shelf and Berkner Island. A small partial eclipse of the Sun will be visible across southern Africa, Tasmania, and southern Australia.

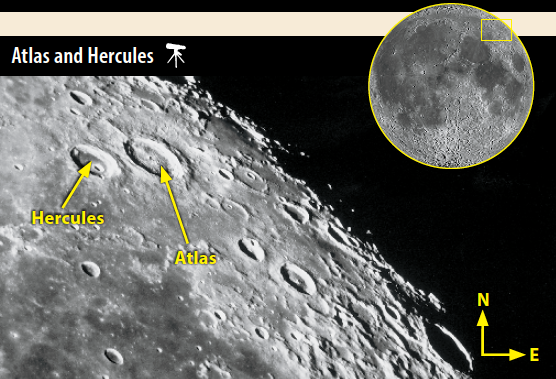

Rising Moon: Nested craters

It’s easy to find twin craters side by side or small circles inside much bigger ones — they’re everywhere — but a Goldilocks bowl that’s just right, nestled inside its parent crater? Boussingault in the far southeastern area of the Moon is the best fit. It is visible from the 7th through the 21st, as the Moon morphs from a fat crescent to a couple of nights past Full.

At first glance, you might think that this is a terraced feature, where the sides have slumped inward after the impact excavated a large hole. But after a few seconds, you will notice it definitely has a different appearance: Terraces don’t have raised rims like the inner Boussingault A. Thanks to its far southern latitude, shadows hang around for many days, keeping the double nature distinct from the hundreds of other features in these crowded and rough lunar highlands. There is no central peak here — the original one was wiped out by the second impact, then lava pooled up from below to submerge it all.

Boussingault K, a younger, sharp-edged small crater, adorns the northern rim, clinching the positive identification of your target. An even smaller crater chips the southern flank. As much as the turbulence in our atmosphere permits, crank up the magnification and settle in for a while. Thanks to the shadows and our slanted view, the 3D appearance might give you a sense of sitting in low lunar orbit.

Compared to our view this month, the picture above shows us a bit beyond the limb. The slight nodding up and down of the Moon’s face results from its orbit taking the Moon slightly above and below the imaginary level field of Earth’s orbit around the Sun (the ecliptic). This particular image was taken with the Moon above the ecliptic, revealing more of its underside.

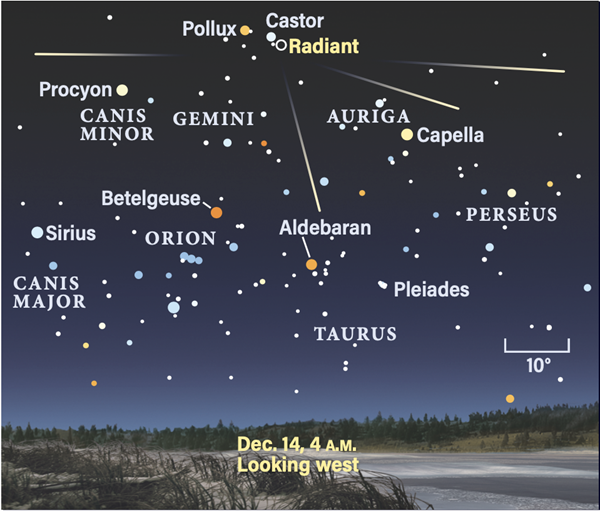

Meteor Watch: One out of two

Two major meteor showers occur in December each year: the Geminids (Dec. 4–17, peaking on the 14th), and the Ursids (Dec. 17–26, peaking on the 22nd).

A waxing gibbous Moon lies in Pisces for the Geminids’ peak, resulting in moonlight interfering until our satellite sets around 3 a.m. local time, offering a couple of hours of dark skies. The Geminids are one of the most favorable shower of the year, with close to 150 meteors per hour when Gemini is near the zenith. Although the Moon will affect this rate heavily, patient skywatchers can wait for the occasional bright event, which are usually spectacular.

The Ursids’ peak is strongly affected by the Moon all night and this year the prospects are very poor for this shower.

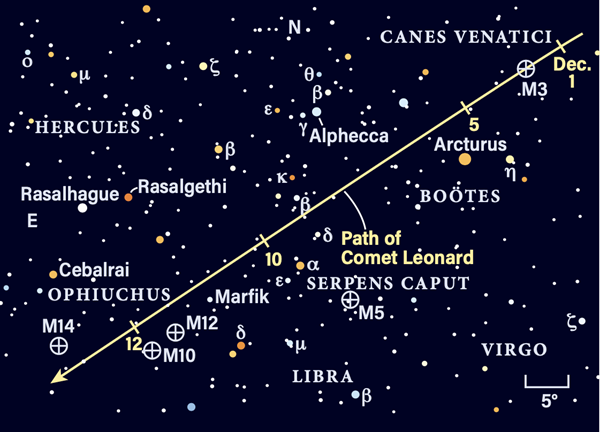

Comet Search: Best comet since NEOWISE

Take every chance you get to observe the brief appearance of Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard). Visible to the unaided eye by the second week of December, it will rapidly fade to 8th magnitude by month’s end. But what a show: An emerald blade shoots out on the 9th as its fan swishes in front of us!

The gas part of a comet’s tail flows straight out, away from the Sun. Almost certainly it will be green, but blue — like C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) — is possible. The dust component spreads out into a relatively flat fan, which becomes edge-on to our line of sight when Earth passes through the comet’s orbital plane. The lightsaber likeness should be present for one night on either side of Dec. 9. It’s not to be missed and worth a drive to darker skies.

Immediately after, the dust begins to blaze, peaking on the 14th. Dust forward-scatters light really well — best when the particles lie between us and the Sun — then fades night to night as the angles change. Don’t be misled by thinking Gregory Leonard’s comet will be best when it comes closest to the Sun (perihelion) in early January. More important is the increasing Earth-comet separation. Brightness drops by the square of the distance between two objects, meaning Leonard will fade to binocular brightness by the time we hit New Moon.

Beware of the confusing information on when to view Leonard. Technically, it is visible both after sunset and before sunrise in different parts of the sky. In a nutshell, here’s when it’s best: Up to Dec. 12, look southeast as dawn is breaking. From the 12th onward, switch to early evening and look low in the southwest. Find observing spots with as low a horizon and as minimal light pollution as possible.

Note that our illustration shows the comet’s progress only through Dec. 12. Visit www.Astronomy.com/skythisweek later this month for charts and viewing tips through the latter half of December.

Other visible comets this month include, in order of brightness, 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, 9P/Borrelly, and C/2019 L3 (ATLAS).

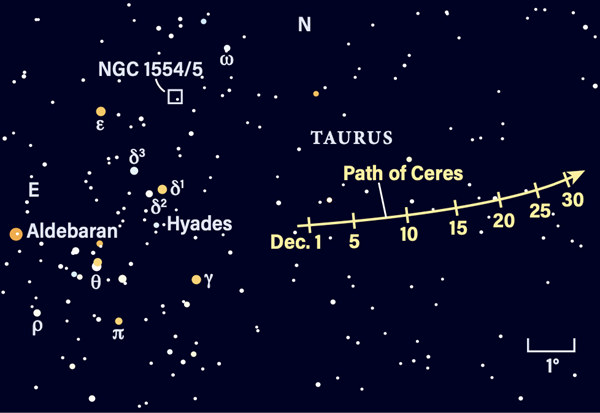

Locating Asteroids: Ceres from the city

While dwarf planet 1 Ceres quickly crossed the star-studded face of Taurus the Bull last month, it now begins a stroll into the populated Milky Way. The space rock is perfect for binoculars from the suburbs, having just peaked at magnitude 7 on Nov. 29 during opposition.

As bright as Ceres is, it can almost hide in the crowd. Scan the chart below or print out a larger-scale copy to mark when you saw it. Use the 6th-magnitude stars as your pattern anchor to positively identify the right dot.

It was back in 1801 that Giuseppe Piazzi was comparing telescope fields with star charts and picked out this undiscovered planet. Like him, wait a night or two to confirm its motion against the background. At month’s end, Ceres has faded a whole magnitude, but is easier to spot in the sparser starfield.

Earth now pulls ahead on its inside track, lapping Ceres in 2023. The paths are not round, however, which will bring the main-belt asteroid slightly closer to Earth than it’s been since 2005. These brighter oppositions come in cycles of nine and 14 years.